Advertisement

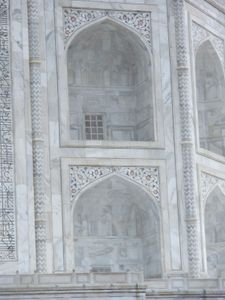

Double-tiered Inlay

Double-tiered Inlay

And when the sun strikes it...I take joy in the stupidity of others. It also relieves boredom.

Our rail coach contained blend of foreign daytrippers and uppity Indians who enjoy bossing service personnel around as if they were unresponsive oxen. Across from me sat an antsy Indo-Frenchman leading a group of college interns on a three-day excursion from Delhi. Conditions were ideal to begin with: I had been assigned a window seat and there was a table in front of me to place my notebook. I could stretch my legs to their full length below the seat facing me. Better yet, the seat next to me would remain empty for most of the journey.

He had an Anne Rice novel to pass the time, but kept at his cell phone too often to knock off even a few paragraphs. The train gently jerked forward. The multitude of humanity scattered on the platforms of New Delhi’s train station soon disappeared. He couldn’t resist and to be fair was only trying to be polite. But in the book of dumb questions, his gets honorable mention.

“Are you going to Agra today?” The train’s final destination was Bhopal, so either I was getting off at a mysterious destination in

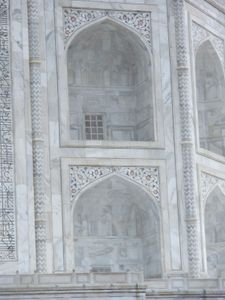

Watery Image

Watery Image

It's why they call it a reflecting pool...the next two hours or rolling on to a city whose only claim to fame for foreigners was a chemical catastrophe nearly twenty-five years ago.

I leaned towards him, surreptitiously looked left and right with my elbows on the table between us. My forefinger pressed up perpendicular against my lips. “Shhh!” I whispered at him. It’s a secret!” Perhaps he would have picked up on my sense of sarcasm. Taking a look around, all foreigners were checking out at Agra.

“Ah to see the Taj Mahal?”

I tilted my head and scrunched my eyebrows. “The what? Taj Mahwho-?”

“It is OK. I will show you.” I have concluded over the years that Indians have a serious streak of being way too instructive. He went into his over-the-shoulder briefcase and pulled out a guidebook, flipped to the appropriate page, and put it in front of me. Before I could take hold of it, he withdrew the book. “Oh, but it is in French. Can you read it anyway?”

“Oh, I don’t know. I’ll try.” So next to him he has a thirty-seven-year-old American who thinks he might be able to read French and has never heard of the Taj Mahal. In

A Bend in the River

A Bend in the River

The Yumuna flows to the Ganges...fact, he can’t even pronounce it. Yet the group leader isn’t the least bit suspicious. Gullibility has the best of him.

I take the book from him. It is a poor one, like the old fashioned Baedekers back in the days when only jet setters could see Europe in proper fashion. I pretend to study it and let my mind race back through the months of research leading up to my boarding this very train south.

“Wow…looks interesting.” He smiles at me, pleased that he has enlightened me. “I think I will try to get there. Do you think it will be hard to find?”

Let’s face it. Travel in India was meant to happen by train. Buses are great to fill in the gaps, but there is no equivalent. It is true what they say about the legacy of the British Empire on the Subcontinent. Its greatest gift to the development of India was the rail system, however unintended it may have been for its subjects. I would argue the English language is a very close second.

I have always connected Second Class service as being fit for middle class folks. Second Class suits me. I will not

Sandstone at its best

Sandstone at its best

A palace within a palace...Agra Fortentirely rely on it because I am unmoved by the theory the kindest folks go with the masses. Even now, I think about when would be a good time would be to go Sleeper Class. Our coach staff plow up and down the aisle dropping us goodies with each visit. First it is a selection of three daily newspapers, all in English. This sends one in our group of six into a little hissy fit until a service boy comes back with a paper in Hindi. I offer him a glass of water from a two-liter bottle that each passenger receives after departure. “For me?” he inquires.

“Yes. Here.”

He takes it, downs it, and returns to the section on cinema in Delhi. I don’t even a thank you.

Then Indian Railways pours soft piano music through the speakers.

When not having ridden in a train for a while, the next time is like the very first. It is an inner and private thrill, like the feeling as a child in the back seat of a car. Remember when Mom drove over a dip at high speed and you got that instant feeling of suction in your stomach? And you

A Boy's Toybox Come Alive

A Boy's Toybox Come Alive

With a girl's interior touch...loved it? Yep, that’s what train travel is like. And I have graduated to the top: I am in India.

Or so I still believe. On my left, I see New Delhi train station giving way to high concrete walls atop of which are sharp steel pickets of peeling paint. Nomadic cities of plastic and corrugated sheet metal whiz by under highway bridges. Puffing industrial plants churn solid particles of something unpronounceable into the thick, damp air. Decrepit villages latch onto the tracks as some sort of connection to modernity. About a dozen beaming boys play sandlot cricket next to tents they call home. On my right, a Korean couple delights themselves with satellite coverage on their Blackberry. Two British tourists challenge themselves to see which one can count the most men relieving themselves in fields of high thicket. Both chuckle and enjoy the repulsion. By my quick estimate, they should score in the hundreds. Barracks of mini grass huts stack up against each other in fields of sloppy rice paddies. More youngsters splash in stagnant, oily ponds; a few of them use the immersed water buffalo as a diving board. The Korean woman’s Blackberry just shot off a tune,

Why Did the Power Go Out?

Why Did the Power Go Out?

Could it be because of a few lapses in attention?Hannah Montana. I hold in my breakfast. Oh goodie: an email from Mom.

My jaunt on the 6:15 Shatabdi Express proves that for the non-Indian, Agra is simply an extension of Delhi. No one has to cut ties. The sightseeing can go one and still be umbilically attached to The Wonderful World of Benetton, Pizza Hut, and Ruby Tuesdays. Let’s call it the way it is. For most tourists, Agra is Delhi’s branch office.

To the best of my memory, I didn’t request a wake-up call. However, when the scratch-like knock came at 5:30, it annoyed me almost none. The whaling from the mosque had already roused me from my sleep. Darkness was evolving into mild shades of grey. I wanted an early start anyway: Let’s get through these few compulsory days before the journey really gets underway.

Again there was a scratch. Odd. Maybe this is how Indians knock, a cultural idiosyncrasy. Who could it be? I opened the door and looked across at the opposite wall. Nothing. I rubbed the caked muck out of my eyes to look left, then right. Still nothing. Had the sound come from elsewhere? The bathroom? Then I had the misfortune of looking down. And there it was: a hunched over chubby chestnut monkey. Seated, it came to the height of my knees.

When we made eye contact, it let out a cackling scream at me. I of course, did the same, but with both feet off the ground. Just to be clear on this, I screamed, a Poltergeist, Shining, It kind of scream. Fearing it would lurch at me, I let out a Three Stooges stuttering utterance like when Curly and Moe sprint away from the bad guys. Then I slammed the door shut and Curious George scampered down the hall to seek out another victim. Within thirty seconds my pulse had dropped well below two-hundred and respiration half that. Thankfully I was wearing no pants of any kind. So a change into a clean pair would not be needed.

“It’s amazing what you can do with some marble and an endless supply of expendable labor” is the way I shattered the silence. The three of us looked up at two of the minarets, the bulbous dome, and follow the crusty lines of finely cut stone. The two women from Melbourne were lost in some soap opera-like fantasy of a handsome monarch who commissioned the construction of the world’s greatest act of love for the eternal - barf, barf, barf. I never caught their names. But my comment ensured that I wasn’t about to.

“What was that?” one demanded.

“I mean, this guy was on one helluvan ego trip when he thought this one up. For a woman? That’s it? One person? Whoa.” Its only justification is that Shan Jahan’s beloved passed away during the arrival of their, get this, FOURTEENTH child. Fourteen! Come to think of it, deliver a dozen or so offspring and live to tell about it, perhaps the Taj Mahal might be just the right way to show one’s appreciation. The facts did not get in the way of the ladies trying to lose me. How many perished in its construction? What was the human cost? How did this benefit anyone? Oh, lest I forget: it was for love. That’s all that matters. Puh-lease.

It has been injected into us by our pediatricians. Our mothers fed it to us for breakfast. And where National Geographic documentaries failed, our seventh grade social studies teachers made up the difference. Yes, I admit, the Taj Mahal is what it’s cracked up to be, but all the hype has made this marble giant more than the sum of its parts. The bar is set so high. It is the culmination of an expectation already met, and one almost impossible to surpass.

I like being here and strolling the well manicured but sterile gardens. It is the only sanitary and quiet piece of real estate I have encountered in a week. The Taj surveys the banks of the Yumuna River as it arcs its way to the Ganges. Three hundred yards away, farmers till the river’s edge with hoes for crops. On my side, four minarets, one in each corner but never perpendicular, tower to join solitary birds and the haze. (Legend has it the towers lean slightly away from the mausoleum in case of an earthquake. Then they’d fall away. Frankly, I cannot see this.) The reflecting pool catches the finest details of gemstone inlay and Arabic script.

The octagonal interior’s acoustics is a four-hundred-year-old amplifier, superior to that of what most rock bands use when performing at professional basketball arenas. Not only does sound not shrivel away, it seems to increase three fold, much to the delight of children. They test the architecture’s design with bursts of yelps sure to awaken the dead. But there is no movement from either tomb. Unfortunately no parent delivers a proper blow to keep his child from ruining the ambience. The marble lattice protects the tombs of the Mughal ruler and his beloved from direct view. The dark cavern is lit by a single, still, and pendulous lamp. The cord reaches straight to the top of the dome.

The disdain I have for insolent children is matched by the same contempt I have for mass disrespect and failure to absorb a special place and time. Few monuments outdo the Taj Mahal. One of the fundamental principles of Islam (Oh by the way, the number of tourists who referred to the Taj as a Hindu monument was frightening) is the absence of human images at its centers of worship. The same respect should be observed when visiting the Taj Mahal. Put yourself in front of it while a shutter of any camera closes, and may you be forced to listen to a second grader play “Twinkle Twinkle Little Star” on the violin for a month straight. Humans were not meant to scourge the symmetry and precision of the Taj. Just leave it alone.

But not Becky and Rhonda from Oregon. Oh, no! Rhonda positions herself on the platform so that, through the viewfinder of Becky’s camera, their ideal result appears. Rhonda stands at the Gateway to the main gardens, from where most iconic photos of the frosted marble fantasy are taken. She throws both arms in a flowing motion to the Taj behind her, flinging her fingers and a manufactured, superficial smile. Rhonda holds the pose as Becky clicks the camera. She has become Vanna White on Wheel of Fortune ready to turn another vowel on the orders of Pat Sajak. Back in Eugene, she will look as if she personally delivered this great discovery to her sorority sisters, all thanks to her.

I sit down at the Jawab, a building to match its symmetrical opposite on the west side of the Taj. I am alone. As the morning buses arrive, there is little time to examine the concave arches, slight differences in the chrome sheen of each stone, and wait for the sun to perforate the clouds. When the rays smack the shiny semi-precious inlays, I conclude there is nothing more I can ask. It has delivered as promised. Traversing India defies perfection; it cannot happen by definition. Though this is about as close as it gets.

An unfortunate yet natural adversarial relationship exists between foreign visitors and third world taxi drivers. In dire need of revenue, many drivers highball potential passengers in order to secure the little extra they think their potential and gullible victims are willing to pay. Even if Inga and Sven refuse and ride with someone else, eventually someone out there will agree to the inflated quote, which serves as compensation for two or three lost opportunities at business. In enclaves where tourists magnetize to each other, like Agra or Khao San Road in Bangkok, I have even seen drivers collude to keep the prices artificially high in their part of the city. Rickshaw or tuk-tuk drivers see no wrong in milking a few more drops from people who will have made no investments in anyone or anything except themselves. What is a dollar here and there for a Westerner amounts to dinner for him and his family. We need to get by, squeak by in most cases. We live day to day, they say. Foreigners don’t understand our world. And they’re right. No damage is done, so what’s the harm?

On the other hand, the tourist takes this as an affront to proper business principles. He feels (and rightfully so in my opinion) there should be a fixed price for everyone, some universal code of just commercial practice. In the dog-eat-dog world of capitalism, decorum, truth, justice, and the American way should reign supreme. We’re on a budget, too, we say. What more do they add to the argument? We have saved for months if not longer to come to your country, provide you with a means of an income to better yourselves. Just how would you get by without us? Anyway, there are more of you and there are of us. So we’ll just walk down the sidewalk until we get what we want. By and large, the tourist is right and gets what he wants.

Something has to give.

What ensues is a game of mercenary cat and mouse until a deal is fulfilled or both parties realize none is possible. Drivers are notoriously aggressive and will follow tourists for the better part of a kilometer hoping they’ll relent in the War of Attrition and hop in. This rarely applies in my case. Others have a few weeks to execute their agenda. I have much longer. Time is on my side. Cycle rickshaw drivers are equally as in-your-face, but with a twinge of despair twisted in. Like anywhere else in the world, it’s a man’s job. He will gently approach from behind, nudging a fender or spoke into my ankle. The conversation goes more or less like this:

“Hello my good friend! How are you?”

I stay silent.

“Very hot today. You need ride. I give you ride.”

More silent treatment.

“Only fifty rupees. I take you anywhere in Agra. OK, my friend? What country are you? German man? Canada person?” His price is above and beyond what anyone should pay.

While maintaining my rigorous gait on the shoulder, motor traffic zips by the both of us. They’ll hit the cycle before they hit me. So at least the annoyance comes with an unintended element of safety. I turn to the left and see an Untouchable, a Dalit, raking through chards of glass with three fingers. He picks up strips of rubber below a few smashed bricks. Still I say nothing. Then I cross the road, hop the median, thrust my hips forward and back so as not to become a permanent ornament on someone’s bumper, and continue on the opposite shoulder. Did I ditch Ramesh? Nope. He slips right in behind me and resumes his pitch.

It is unconvincing. For five to seven more minutes, he assails me with numbers, destinations, and stories about how great my country is, whichever that happens to be. I still haven’t uttered a word. I turn violently to the left and take to a road leading away from main traffic, into the bowels of an Agra of which I am certain no posters hang on the walls of travel agencies. A camel train of three beasts trots along with hundreds of cucumbers in tow in a bullock cart. Fifteen yards behind the camels, an elephant with a single master on its shoulders follows along. Both species pay me no notice. The pachyderm’s left hind quarters brush up against my forearm. If it slips or loses its balance, I’m in the hospital for a week. Odd, there are certainly no tourists in the area. This isn’t a zoo, at least not for animals.

I had walked as far as I was comfortable, content with my incursion into the scorching naked city. For me to backtrack to my hotel would take me about ninety minutes. It was near noon. The sun’s rays thrashed my face. Suddenly, Ramesh, the trooper that he was, was looking like a viable option. For the first time since we converged on each other, I acknowledged him.

“Taj Ganj. OK?”

“Yes, yes, my friend! We go!” He could barely hold back his delight.

I made no motion to the back platform of the rickshaw. I had been programmed over the years no to trust his type. I never get in without securing a price. “How much?”

“Forty rupees.”

“Twenty.”

He paused for maybe three seconds. “OK.” My God, he really needs this fare.

I climbed aboard. His bottom rarely made contact with his worn seat. Watching him pedal in the standing position, he reminded me of someone struggling on a treadmill for the first time at a fitness center. He turned right on a main road; there was no shade. He never hesitated except for the times he had to dismount and walk me up sharp inclines. His demeanor never soured and his art of conversing about Agra never swayed. His brown hair was a stained yellow, perhaps from the lack of care, I do not know. But it did not look natural or healthy. Sweat poured down the back of his neck as if a hose had been opened on the top of his cranium. He was about the same age as my father.

It was a half hour back to my frosty hotel room. The twenty rupees we agreed upon would buy him cold water to replenish all that he had expended to get me there. I dismounted in front of the elevator and handed him a fifty rupee note. He went into a pocket of a shredded pair of pants for change. I handed him a Connecticut lapel pin; he was delighted and affixed it. He extended me the change, thirty rupees, about seventy-five cents. I smiled, said thank you, and that he could keep the change. I went away forlorn. That man deserved better than the treatment I handed him. Never once did he complain, grunt, or breathe hard. Somehow, I could have done better. I wanted to have done better.

I really need to reconsider my tactics.

Ramesh collected me near Agra Fort. It is the Mughal version of what a little boy would build in his sandbox, but his would be in microscopic miniature. When the last pail and plastic shovel were out of the way, the girl next door would come over and do up the interior. Shan Jahan’s walled playground is the size of one of those floating cities you see in science fiction movies, a medieval death star of its time. It is so enormous, you’d think it is on a hill. But no. The base of the sandstone, castellated ramparts are at street level. From one end along a straight line, it is so long that it is impossible to see the where the walls finish. They may as well go all the way north to Delhi. Within the fortification are patios, mosques, gardens, and courtyards, all decked out in the same combination of sandstone and marble of its more famous neighbor downriver. From the regular intervals of bastions, there is a sensation that Agra fort looks down upon the Taj Mahal; it is that immense. Furthermore, the human history behind it is far more powerful, one of a son betraying his own father. Shan Jahan spent the last eight years of his life a captive within its walls until Aurangzeb sent his father’s remains to be interred next to his beloved at the Taj. Before the capital was transferred to Delhi in 1658, Agra Fort was the administrative center of absolute power in the Empire. Under British rule, it served as an arsenal deposit for its military operations, an insult to its former prominence. In modern Agra, the Fort is an afterthought, the self-respecting and handsome stalwart of a supernova neighbor. Imagine you’ve won the Final Four for three straight years singlehandedly on buzzer-beaters in overtime, only to wake up years later to the realization that Michael Jordan lives next door to you. I gladly poked and prodded my way through the Fort, rather content to be alone. A few families spread out on the putting green lawns for a chance at photos with their children. The courtyards are lifeless and hollow, even as the grandness of Jenaghir’s vermilion rust-toned palace of carved false windows in marble trim on the façades of its mosque would draw the ooh’s and aah’s of throngs of visitors…if they’d bother to take the time to come. Perhaps that’s a part of their pre-set program for the afternoon portion of their tour.

People can tell what day of the week it is by focusing on the details of any photograph in which I appear. If the top of my head bounces back the sunlight or that of a flash, it is earlier in the week. If there is visible grey and orange stubble in my sideburns, figure it to be Friday afternoon or even Saturday. Consistently available hot running water not part of the Indian landscape, I decided to leave my grooming to the professionals.

Calls of “Beer! Wine! Marijuana!” follow me through the tourist quarter of Taj Ganj. The few obstacles between me and the entrance of the barber shop pose little difficulty. A grey sow grunts softly as its snout turns strips of mango peels. Its udders and abdomen drag against the earth. The sewer ditch is only a foot wide and thankfully flowing. I jump over it. My barber greets me as if I have been a lifelong customer. Though not completely sure, I believe he put me at the front of the line; others who were before me waited as I took a seat on the old style stools with the adjustable pad to support the customer’s neck when inclined. The shop is no more than a concrete indentation, the size of a walk-in closet for a master bedroom in a Connecticut McMansion. Three barbers work here without miraculously ever bumping into each other, a relief since their tools are all hand held and lethally sharp. The chatter is most likely of the happenings in Agra: sports, and who is doing what at their jobs. I am at ease when I make the cultural connection: barber shops are all the same. Same attitude, same patriarchal barber who rarely speaks, lets the customer shoot his mouth off, and winds up knowing every embarrassing secret about everyone. Mine is covered in the scraps and locks of his previous customers; damp clippings hang from his grey chest hair. I motion that I want a clean shave, all the way around. He puts a new razor in the switchblade, shoves the palm of his hand into my chin and constricts his thumb and middle finger against each side of my jaw. I am immobile and mildly uncomfortable with the Half Nelson wrestling move he has put on me. But he has a razor at my face. I stay silent. A faint bead of sweat drips from my temple as I see the thin silver instrument cross me at eye level.

No one has ever administered me a better shave. Not only was every last follicle plucked, he also went at my eyebrows, ears, and nose. At no time did he or his colleagues use any electrical tools. At the foot of each stool was a pail of water; none fell from the faucets. Oils and gels came out and were the scrunched into my scalp. The face massage that came last was just a few strikes short of assault and battery. Ike never slapped Tina around as vigorously. Six dollars later, I stepped away with self-contentment. I was powdery and smelling like a bouquet shop. By the time I got back to me hotel lobby, I was again drenched.

Advertisement

Tot: 0.043s; Tpl: 0.016s; cc: 11; qc: 25; dbt: 0.0184s; 1; m:domysql w:travelblog (10.17.0.13); sld: 1;

; mem: 1.1mb