Advertisement

Geoffrey

Geoffrey

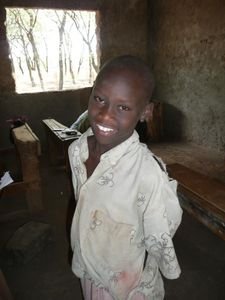

Geoffrey when he first started to help meA wide smile and clear bright eyes smiled at me from a dirty torn patterned shirt as the young boy curiously watched me talk to the women. As I showed my colourfully dressed group the video camera and encouraged them to try filming each other the boy was ever-present, laughing and pointing at everything that was going on. This was Geoffrey. From the first day that I had visited Sandai he had been around, following me when other children withdrew. He was accepted everywhere and at first I had been told that he was crazy but it soon became evident that he had a different disability. He was deaf.

He soon started to come running when my car appeared in the village. As I unloaded equipment from my car he would stand close and gently touch a bag or camera. He was excited by this change to the mundane life in the village. I was a new event in village life and people were welcoming eager to work with me and learn to use a video camera to record their lives. On an early visit I gave Geoffrey the tripod to carry and pointed to the hall where I was

meeting the women. He smiled excitedly and ran off to the room eager to help me. Although he was limited in hearing and had never been schooled properly I began to realise that there was a bright, intelligence behind those shining eyes.

Slowly I started to learn more about the boy. At first I wondered if there was a mental disability too as his restless nature gave him an over excited approach that was very different to many other African children. These would at first excitedly crowd round en masse but as soon as I talked to individuals they would usually back off shyly. If pressed they would perhaps whisper their name so quietly that I could rarely grasp it. In fact, young children and babies would usually scream in terror at this strange white face talking incomprehensively to them. Geoffrey was different, unafraid to approach but always gentle, questioning, curious yet his ready laughter made me wonder if there was another problem.

It was evident how he was loved and accepted in the village. No one turned him away from my meetings and there was obviously a communication of sorts between him and others. He could make

Geoffrey helps

Geoffrey helps

Geoffrey helps with the womens' film crewsounds which those who knew him well interpreted as words. His uncle, Samson, who was also learning to use the video camera told me more about him. His family were poor hill people and he came from a large family. Because of his handicap he was regarded as lacking intelligence and from an early age left to his own devices and he was probably attended to less than his siblings. Not discarded by his family but with the hardships of finding food for all the other mouths to feed he came last in family care. Now he was about 9 or 10 and for many years had lived a nomadic life, wandering from house to house in the village centre, seeking company, food and shelter but rarely staying more than a few days in any one home. For a while he had followed Samson’s children to school but his ‘education’ was informal and his restless nature meant he was happy to roam free.

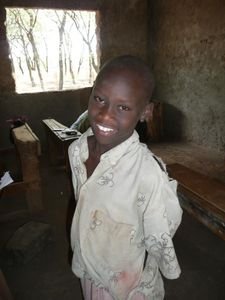

As he joined in the filming I occasionally trusted him with my camera and he quickly grasped how it worked but also would look carefully at the screen and take some surprisingly well studied photographs. I

Geoffrey's photo

Geoffrey's photo

This was one of the first photos that Geoffrey took with my cameraenjoyed his company as I worked and he obviously took delight in feeling that he was accepted and belonged - and was doing something that the other children were not. On a visit to the local town I went to the mtumba (market) and bought him some second hand but more respectable clothes. The transformation was remarkable from a tatty neglected boy he turned into a smart child in his new football shirt and denim shorts. The delight shone out of his eyes and he grasped the black bag of other clothes tightly. Suddenly he had possessions of his own.

I would also let him ride in the car the few hundred metres from the hall to the village centre. However after one long day of filming, with Geoffrey participating by helping carry bags and fetch sodas, he was reluctant to get out of the car. However I lived in Loboi, another village about 4 kilometres away from Sandai so we had to coerce him out of the car. As other people piled in for a free lift along the dirt road between the villages, he clung on to the outside of the car and tears welled in his

uniform

uniform

Samson with Geoffrey at his new school in Nakurueyes. Samson gently took his shoulders but Geoffrey was obviously sad that his day of fun was over. As I pulled off my own eyes were full of tears and I wondered how I could help this lost soul. One day, I planned with my local assistant, Anderson, we would take him to the Lake Bogoria National Reserve, next to where I was staying, to give a him a treat and show him the flamingos and other wildlife.

Back in Loboi, I joined the science team that was temporarily in residence at camp for dinner then fell into a deep sleep in my tent. The next morning as I talked to students at breakfast I caught sight of a familiar figure in blue denim being fed at the camp kitchen. How had he got here? Anderson told me that he had appeared in Loboi village at about 10 the evening before. Evidently as soon as my car had gone he had set out to follow on foot and arrived in the dark of night. Anderson had kindly took Geoffrey in and his own family had readily accepted the boy.

He was soon adopted by others in the camp. Even the camp manager, who usually fiercely guarded the camp from freeloaders indicated to him to go to the kitchen to be fed and suggested we gave him some pencils and paper to see if he could draw. He seemed so happy to be at camp that I hadn’t the heart to send him home straight away and enjoyed having him around as I tried to catch up on some writing although found I was distracted by his curiosity to look at pictures on my computer or use my camera. He was content to draw for a short while and could partially copy letters and numbers but when I tried to indicate for him to copy a sketch of a dog he did not seem interested.

In late afternoon Anderson and I took him for a trip into Lake Bogoria Reserve as planned along with Judith, a girl from Loboi who I was already funding to go to school. Geoffrey’s eyes sparkled as we drove along the bumpy track in the park. He alternated between making exuberant sounds at each creature we saw and falling silent with amazement. Gazelles, flamingos, warthogs and the strange sights all disappeared through his eyes to his brain and I wondered what he was thinking. How could and did he comprehend things without the power of having learnt knowledge through the spoken word? What did he make of this world were his communication channels had been restricted? That he was resilient and able to cope with daily hardships was evident but how did some one’s mind grow up without speech?

A pair of dikdik (small antelope about 18 inches high) crossed our path and Geoffrey pointed at the animals and gestured an eating motion putting hand to mouth. I knew where some of his family meals must come from even though poaching of wildlife was illegal. When extreme poverty forces hunger how can conservationists criticise the necessity of bush meat for subsistence? The local communities have been educated and sensitised in many aspects of environmental conservation. Initiatives have been developed so that they diversify their livelihoods in ways that will promote sustainability of resource use. Yet when many live at subsistence level on less than the dollar a day poverty level it is hard to criticise traditional hunting practices. New ways have to be sort so that it becomes unnecessary.

Later in the evening I phoned Samson to say that the boy was in Loboi and that I would drive him back in the morning. He had been missed and Samson was worried. As Anderson took him home again I started to plan how I could help the boy more. Although the day had been fun and I enjoyed having the boy around I needed to get on with my studies and he was ‘disturbing’ as Judith had put it. The need for a schemes to help him became even more obviously necessary when at about 7.30 I heard a sound at my window. There was Geoffrey, having run off from Anderson’s home to join me. Oh dear. He so wanted to belong somewhere. I was very fond of the boy and my heart went out to him but I could not adopt him or take him in. So I spent an hour wandering around in the dark of the village trying to find somewhere for him to stay. I did not want to take him to camp as he was not wanted there. Anderson lived about a mile away so eventually I paid for another local friend to stay with him at the local hotel although for a while Geoffrey cried and strained to follow me back to the house again. I urgently had to find a solution.

Next day I made enquiries with Samson and we decided to try to get him into a school for the deaf in Nakuru although first I had to consult his parents and village chiefs. Although he was neglected in education he still belonged and was loved in the village. I could not presume to ‘educate’ him without approval of his family and elders. The village chiefs were grateful for my plan to help and agreed that really something should have been done for the boy before. I tried to ask the people in Sandai to watch Geoffrey so that he did not follow me to Loboi again. I was happy for him to be around while I worked in his village but needed my evenings for study and it was inappropriate for him to be at the research camp. However we could not explain this to Geoffrey and he continued to trek after the car to my house and I had to continue to find accommodation for him in Loboi and ferry him back home regularly.

Finally I met his mother, a tall hill woman with a large goiter on her neck, She too was happy for him to go to school. It was not that she did not care but with many mouths to feed a disabled child was paid little attention. She said that he had been born deaf and that it was not through any illness such as meningitis, which is common here. The following Thursday, with Samson, Geoffrey, Anderson and Raphael, I drove the 200km to Nakuru to firstly see a doctor and see if there was any medical help that could help Geoffrey and then visit the school.

The doctor did a brief examination and said that one of Geoffrey’s ears was fully deformed with no eardrum. The other had a small eardrum but with only a little hearing. He felt that surgical treatment was unlikely to work but hearing aids could.

At Ngala School for the Deaf we were sent to see two very kindly assessors who would give a recommendation as to whether Geoffrey was suitable for the school. Isaac Chirchir studied Geoffrey closely. He was happy to do the assessment but before recommending Geoffrey to the school he insisted on meeting Geoffrey’s mother although he seemed to think that the boy would fit in well. He noted that he was cheerful and active but was a little concerned that there might be a slight mental disability. However a quick informal test - presenting the boy with a plastic banana to see if he would try to eat it -resulted in Geoffrey taking one look and casting it on the table in disgust - no mental problem there.

The following Monday I returned, this time with Geoffrey’s mother. We got to the school at about 11 and Chirchir interviewed her. Meanwhile he monitored the boy. Geoffrey as usual was curious and automatically started trying to mend some toys on the shelf, a broken doll with assorted arms and legs and a plastic car with two bears that were supposed to move there arms by linked pulleys to the wheels. His every action showed an inner intelligence and a desire to understand. Everything made him laugh and as the other deaf children crowded round outside he showed a friendliness and eagerness to get to know them. Chirchir’s verdict was that Geoffrey was more than ready to join the school and if he had been educated from an earlier age would have probably been able to fit in and learn at a normal school. He did think that there were signs of hyperactivity but that may be due to the intelligent mind within. He thought that there were a couple of places at the school and that Geoffrey should start right away.

However, despite the recommendation I still had to convince the school. At my request to register the boy, the receptionist sharply said that the school was full and that we would have to return in November for an interview. This would neither help Geoffrey or me. I therefore returned to see Chirchir and use his influence to have Geoffrey enrolled that day. Chirchir was concerned and immediately phoned the head teacher and we were told to return at 2pm.

I took my team to lunch and Geoffrey’s mother tucked into meat and 2 plates of ugali (a stiff maize starch rather like very heavy mashed potato in consistency). I realised how little she and her family must normally have to eat. Geoffrey too ate everything put in front of him reluctant to leave any on his plate although he almost had to force the last mouthful down.

At 2pm we were at the head teacher’s door. He was concerned that I would continue to sponsor the child once I had left Kenya but I assured him that I would make sure payments got there. For full board and education the school charge 5000KSh per term that is around £130 for the year. On top of that is money for essentials such as uniform, bedding and toiletries and transport to and from home. I estimate that it will cost about £250 per year to sponsor Geoffrey. I explained the situation and how I would like to see Geoffrey in school while I was still in the country and finally the head teacher agreed to make an exception and accept the boy that day.

So then we madly rushed around for 3 hours shopping to buy a uniform and other essentials. Geoffrey followed us excitedly round the busy town. When he tried on the blue shirt and shorts of his uniform he was reluctant to take it off. For many years he must have seen other school children all recognisably belonging to a school and yet had only had torn rags to wear. Back at school he perched his thick new mattress on his head and carried it proudly into one of the crowded dormitories with his new friends clustering round signing to him and me rapidly. I wish I knew sign language. One little lad kept stroking my white skin and signing to Geoffrey. The house mother found an empty bunk and Geoffrey placed his new mattress in his bed. It was now getting late and I wanted to get on my way back as I had a long drive back to Bogoria in the dark and rain on Kenya’s dangerous potholed roads. As we signed to Geoffrey that we were going he just looked up happily at us, unconcerned that we were going, clutching his bed and making new friends. We left him there glad that he seemed settled yet I was sad that I was losing my assistant in Sandai.

Geoffrey has been in school now for about 3 weeks. He has settled reasonably well yet his roaming nature has led him to try to ‘sneak out’ into the Nakuru streets so that the teachers are now having to keep a wary eye on him. It must be hard for him who has been used to the freedom of open spaces to be confined within the walls of a school. Yet in the end we all felt that it was the best thing so that when he is grown he will be able to make his own living and not be a burden on his society. I have visited him once and this time he was sad to see us go. Homesickness is still there yet he has new friends and a supportive school. I was impressed at how happy the children were and I am sure that Geoffrey’s Tale will go on in to a better future.

Ngala School for the Deaf has been running in Nakuru for about 20 years. It offers a supportive environment for deaf children to learn. Although families are supposed to pay about 5000Ksh a term I get the impression no children are turned away. There must be many children like Geoffrey who because of a disability are uneducated because of lack of awareness in the community in which they live.

I had some money from a couple of slide shows I had done for a local travel group that would cover his school fees for a year and I have decided to set up a trust fund and ask friends to contribute to his future costs. If anyone would like to contribute let me know and then I will send out details later in the year when I get home.

Finally there are many other able children here that need financial help with education. If anyone feels that they would like to sponsor a child on a regular basis to school please let me know and I will try and set up a direct link. For instance primary education can cost between £5 and £10 per term, secondary education around £50 per term. The cost of a uniform depends on size, for Geoffrey I spent about £35 for two day uniforms and one weekend uniform, shoes, etc. Money for education can be sent directly to the school concerned.

Advertisement

Tot: 0.522s; Tpl: 0.015s; cc: 19; qc: 123; dbt: 0.1617s; 1; m:domysql w:travelblog (10.17.0.13); sld: 1;

; mem: 1.6mb