Advertisement

Published: April 17th 2011

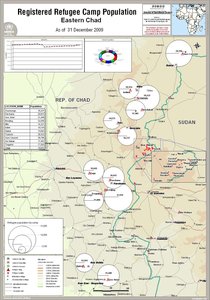

Map of refugee camps in eastern Chad

Map of refugee camps in eastern Chad

There are 12 camps in the east, including Djabal and Goz Amir which I visited during this mission.So this blog has been written for months but I never published it because it seems so boring…all I talk about is work so it almost reads like a lecture! I have tried to punctuate it with a little bit of more entertaining anecdotes but unfortunately…life in Chad just isn’t that exciting (outside work that is). It’s a fascinating country, but things to do in the sense of activities are limited due to security restrictions, so the most exciting thing happening on the weekend is deciding which of 5 restaurants to go to, what movie to watch (again), and what time to go to the pool which I try to do every Sunday. You can’t travel anywhere (of interest) on the weekends so it’s not like Malawi or Thailand where I was discovering new places all the time. I do travel a lot, but only on official business to places in the middle of nowhere where a refugee camp and lonely little humanitarian presence happen to be. So that’s mostly what I have to talk about! My apologies in advance for my boring life 😉.

So a couple of days after my birthday back in September I headed out for

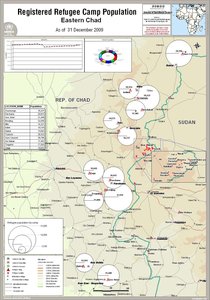

Map of IDP sites in eastern Chad

Map of IDP sites in eastern Chad

This map shows the sites where internally displaced Chadians fled to in 2006, as well as the villages they are slowly starting to return to.my first mission to eastern Chad, which is where all of the refugee and IDP (internally displaced person) camps are. IDPs are kind of like refugees, in the sense that they also had to flee their homes, but unlike refugees they fled to another location within their own country rather than crossing the border into another country. Thus they aren’t in the same need of international protection as refugees, but many IDPs are in extremely poor or war-torn countries that can’t provide assistance for them in their displaced condition, so the international community has to step in. There are around 130,000 Chadian IDPs in eastern Chad (around 50,000 returned to their home areas in the last year), and about 270,000 refugees from the Darfur region of Sudan (which borders Chad to the east). It is important to note that the national boundaries drawn during the colonial era between Chad and Sudan do not reflect ethnic lines, so many of the same ethnic groups are found on both sides of the border. So both the refugees from Darfur and the IDPs were actually displaced by the same conflict ongoing in Darfur, which has spilled over the border into Chad. However they

VIP hubbub

VIP hubbub

There were all kinds of MINURCAT helicopters at the airport in Goz Beida when I landed, shuttling around the VIP mission.do not live in the same camps; there are refugee camps, and separate IDP sites. In southern Chad, there are also about 57,000 refugees from the Central African Republic (CAR, which borders Chad to the south) who fled conflict there. One of the maps I posted shows the 12 eastern camps for refugees from Darfur; the other map shows the IDP sites that are scattered throughout two areas of the east. (They're out of date in terms of exact figures, but the locations haven't changed.)

UNHCR’s mandate under international law covers refugees, however because of the agency’s expertise in dealing with protection of refugees, whose circumstances are very similar to those of IDPs in practicality (though not in legality), it is the lead agency for IDP protection as well. So in sum, UNHCR is responsible for refugee protection, and is the lead agency among several responsible for IDP protection. In any operation, UNHCR contracts partner organizations, usually international or national non-profit organizations, to carry out some of our non-mandate activities for which another organization has expertise. For example, in one camp we may enter into an agreement with the International Rescue Committee to carry out health activities and with

Still some green in the desert

Still some green in the desert

This was just at the end of rainy season so the landscape was shockingly green.the Jesuit Refugee Service to carry out education. So these are the actors you find in Chad – and there are a LOT of them. Especially because UNHCR is the only agency that works exclusively with refugees and IDPs. There are a lot of additional UN agencies who deal with all kinds of issues in Chad and

not in the refugee camps, such as chronic malnutrition in the Sahel belt, droughts, epidemics etc. that affect the national population. I have never worked anywhere with this many other actors on the ground; besides tiny little taxis and thousands of motorbikes, the roads in N’Djamena are most traveled by SUVs blazing logos for every NGO known to man including Oxfam, International Rescue Committee, the ICRC, Medecins Sans Frontieres, CARE, ACTED, Intersos, JRS…to tons of UN agencies like IOM (migration), UNICEF (children & education), OCHA (coordination of humanitarian activities), WFP (food security), UNFPA (development and gender), FAO (agriculture), WHO (health), UNDP (development)…the list goes on and on. Not to mention all the national development agencies like USAID, ECHO (Europe), GTZ (Germany)…

My agency, UNHCR, has 7 field offices in eastern Chad, interspersed among the refugee camps not far from the Sudanese border.

To reach the east UN staff can only travel by air; UNHCR and the World Food Program (WFP) have a joint aviation division which operates special flights for humanitarian workers all over Chad, until December MINURCAT also operated flights that UN staff could fly on. The eastern hub is Abeche, about a 1.5 hour flight from N’Djamena; from there smaller aircraft shuttle people to the field. On my first flight east, departing N’Djamena at 7am, I was amazed to find the airport check-in lounge chock-full. There are only a handful of commercials flights a day, so in the early morning the airport is totally taken over by humanitarian workers lining up for various UN flights to the field. After changing planes in Abeche, I flew to Goz Beida, which is a small town in southeastern Chad. This plane was by far the tiniest I had ever been on, with no separation between the pilots and cockpit whatsoever, and only one pilot! The second cockpit seat was empty. (Don’t think I need to tell you the degree to which I freaked out on that flight, which thankfully was only a half an hour long.) That plane was actually flown by an

American NGO called AirServ which is funded by USAID. All the pilots are American and live in Abeche. My pilot on this occasion was a woman, which I find extremely cool. Her name is Lauren and she has been flying here for a few years already, bless her heart!

When we landed in Goz Beida and I climbed out of the tiny plane there was a row of military officers lined up along a red carpet…not for me, alas. I happened to be landing at the same time as a VIP mission that included the Representative of UNHCR and several ambassadors who were going to visit an IDP camp to discuss with the leaders their situation and what their feelings were on returning to their areas of origin. I also happened to visit the same IDP site that day as part of my mission, and was lucky enough to sit in on this meeting. We sat in a small hangar constructed of wooden poles with a tarp as a low roof. The leaders sat on reed mats, the VIPs on plastic chairs. I squeezed into what little standing room there was by the entrance to listen in to the

conversation, then set off to my own meeting, in another nearby hangar, for a meeting with IDP women.

The purpose of my mission was basically to get a sense of what the situation is for refugees and IDPs, what partner organizations are responsible for what activities, how they carry out their activities, what the major protection issues are, etc. Sexual and gender-based violence (SGBV) is one of the major challenges for us in Chad, both in the refugee camps and IDP sites. You’ve probably heard of female genital mutilation (FGM), which is sometimes euphemistically referred to as “female circumcision” though it is in no way innocuous or healthy. (To read more about FGM click here: .) FGM, which is considered to be a form of sexual and gender-based violence, is widely practiced among the ethnic groups living in Darfur and eastern Chad. A girl who has not undergone FGM is usually ostracized by her community and will not be able to get married. It is such a strong custom, and the social pressure so high, that despite truly horrific health consequences, mothers will force their daughters to undergo this procedure, usually by the time they are 10 years old.

Child marriage, another form of SGBV, is also widely practiced – girls are typically married around age 13-14, though sometimes as young as 10 (and usually to men much older than them, and often as second, third, or fourth wives). Child marriage is causally linked to health problems (e.g. complications during pregnancy and childbirth) as well as social problems (domestic violence is often triggered in such cases because a child bride is often unable to cope with the rigorous demands of maintaining a household, fetching water, cooking meals, raising children, etc., which are considered to be her duties regardless of her age). We suspect that rape and sexual assault are also huge problems in the camps, though it is very difficult to obtain accurate statistics on how severe the problem is because most cases go unreported. Rape is blamed on the victim, not the perpetrator—even if she is a child—and the community will go to great lengths to “handle” the situation quietly and without the knowledge of the humanitarian community. “Handle” can mean the perpetrator or his family pays a “fine” to the victim’s family, or marrying the victim off to the perpetrator. There is virtually no greater shame

on a family than having an unmarried daughter who falls pregnant, even if she was raped. This appears to be a large part of the reason girls are forced into marriage at such young ages; parents are so worried about their teenage daughters falling pregnant, to marry them off by age 13 ensures that any pregnancy will be legitimate and thus accepted by the community.

Firewood is becoming a scare commodity in eastern Chad, because refugees and the local population need it for cooking, and have depleted the resources near the camps (despite the fact that the humanitarian community distributes firewood). People living in or around refugee camps now have to travel as far as 40-60km to get firewood, either on foot or, for those who are better off, on donkeys. Collecting firewood is considered domestic work, which means girls and women are responsible for it. (Constructing houses, fetching water and rations (which can come in 30kg bags, something over 60 lbs), etc. are also considered women’s work.) Sexual violence perpetrated on women and girls leaving the camp to fetch firewood has been a very high profile problem, reported in the Western media. The local population and the refugees

Men leading camels

Men leading camels

Camels are everywhere in this region!are in a struggle over disappearing natural resources including firewood, so local men rape women and girls fetching firewood as a tool to terrorize the refugees from leaving the camps. I have often asked women why they don’t get their husbands, brothers, or sons to accompany them when they are fetching firewood, so they go in a large group. The answer is always the same: “They will only rape us, but they’ll kill the men.”

SGBV is a large part of my portfolio, so I spent a great deal of my mission speaking to SGBV focal points in the camps. These are refugees who have been sensitized and trained on SGBV issues, and who work to educate their community about SGBV, and to identify cases and refer them to humanitarian workers who can help get them medical, psychosocial, and legal services. Unfortunately it is difficult to convince victims to report SGBV incidents, because the Chadian legal system is barely functional so there isn’t much point. Perpetrators go unpunished, and victims face retribution in their communities for having “betrayed” the community by reporting the case to outsiders. However the refugee volunteers have made a difference in giving the victims someone

to speak to and educating them about their options. Many young girls in the groups I spoke to were opposed to FGM, child marriage, domestic violence, etc., so even though customs are very strong in their communities, it seems that education and sensitization campaigns are having an impact on the younger generation. I have hope that some of these girls will be empowered to stand up and protect their own daughters from some of these practices, which is crucial if things are going to change.

After a week in Goz Beida I flew in another tiny AirServ plane to Koukou, a more remote field office that serves a refugee camp and IDP sites. Getting to and from refugee and IDP sites in the east requires traveling in a convoy protected from potential risks by military escorts. This used to be provided by the UN peacekeeping mission in Chad, however in May or June 2010 Chad’s president had asked them to leave, on the grounds that Chad was now capable of maintaining security for the humanitarian community and for refugees and IDPs. By September they had already handed over the responsibility for providing escorts for convoys to a special Chadian

force which they had trained, called the DIS. The convoys, depending on how many agencies are on the ground in a particular camp, can contain anywhere from 3-25 vehicles, all huge Land Cruisers capable of making it over the extremely bad roads. There is a set time for departure and return from the camps every day, usually 7 or 8 am, and all the vehicles gather at a meeting point and wait for the DIS escorts to drive past, then the convoy follows. It’s quite a scene, usually the towns our offices are in are miniscule and don’t see any road traffic, and suddenly there is a huge assembly of SUVs.

In Koukou I participated in a big operation in which UNHCR was distributing ID cards to all adult refugees in the camp (some 20,000 individuals). This kind of operation takes a lot of planning, organization, and staff. The distribution in this camp was slated to last about 6-7 days, though I was only there for the first 4 days. The convoy left for the camp at 6am, and we usually got back to the base around 6-7pm. We worked straight through lunch, so it was a very draining

Women walking to an IDP site

Women walking to an IDP site

The women in eastern Chad wear veils with very striking colors that really stand out, even when it's rainy season and there is some greenery.experience. We’d get back to the compound and just eat then crash. The operation had several “stations”—I worked in the community services station, which received all individuals flagged as “vulnerable,” such as elderly people without any family to assist them, handicapped persons, single mothers, etc. In addition to the main purpose of the operation—to get refugees ID cards—it’s also an opportunity for UNHCR to clean up its very sophisticated database in which all refugees are registered and their needs and services provided to them tracked. It ensures that, for example, we know exactly which children in the camp are unaccompanied minors, so we can make sure they are being cared for properly, or to know at any given moment which women are lactating so we can make sure they get special nutritional assistance.

During my two weeks in Goz Beida and Koukou I got a feeling of what it is like to live in a field office in Chad: not fun. There is a curfew, there is nowhere to go, when you aren’t working you are in a walled compound where the living quarters are, in the middle of the desert. Thanks to “staff welfare” policies all the field

"Sage femmes" or "wise women"

"Sage femmes" or "wise women"

Or in our terms, midwives, in an IDP site, explaining how they are trained by our medical partner and what services they provide for women in delivery. office living compounds have air-con and a common room with a few French channels, where everyone eats their meals. The food is, as you can imagine, not much to speak of. Mostly pasta or rice with things that come from cans. Add to that the fact that you don’t choose your colleagues; you are thrown into a compound together with 10-15 people you may or may not like…and that is your de facto social life. I found over the course of the week that despite the communal nature of the meals, people tended to eat them quickly and then retire to the solace of their rooms. I was frequently the only person in the common room! I am sure people would argue that I am painting a bleak picture but…so it is. Work is really all you have in such places. That and the few precious vestiges of home that people bring with them, food like vacuum-packed prosciutto and gorgonzola or hot sauce from Rwanda, or expensive toiletries that may seem utterly pointless but can somehow give you a pretense of normalcy from time to time.

It was nice being back in a field office, in a communal-living situation

During the ID card distribution in Koukou

During the ID card distribution in Koukou

It was a very orderly process, with tables numbered 1-12 and me at table 4, the "community services" table for persons with specific needs such as single moms, elderly with no family, etc.like I’d experienced in Congo, but the field offices in Chad just don’t have the same ambiance. People just work, and then hole up in their rooms waiting for the next R&R (which for people in the field is one week off every 6 weeks). So I am thankful to be in a capital city, where I can at least have something of a “normal” life. I started taking tennis lessons, and one of my colleagues is a former yoga instructor and provides yoga sessions twice a week (sometimes at my house). Most weekends in N'Djamena there is a party organized at one of the NGOs' compounds, which everyone who's anyone attends. They're actually usually very sophisticated affairs, with a DJ, proper sound system, bar, sometimes even a swimming pool! So I can't complain too much. And I get R&R every 8 weeks 😉.

I'm not sure what I will write about next time, if not a lot more of the same...but I will do my best to keep it going!

Love,

Martina

For more information about FGM: http://www.unicef.org/protection/index_genitalmutilation.html, http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs241/en/

UNHCR Chad: http://www.unhcr.org/cgi-bin/texis/vtx/page?page=49e45c226 (has old statistics but a lot of great photos and other

interesting resources)

MINURCAT: http://www.un.org/en/peacekeeping/missions/minurcat/index.shtml

Advertisement

Tot: 0.281s; Tpl: 0.023s; cc: 19; qc: 118; dbt: 0.1221s; 1; m:domysql w:travelblog (10.17.0.13); sld: 1;

; mem: 1.5mb

kpoms

non-member comment

finally!

i'm so glad you finally posted this one, it's so great to hear about what you're doing. please keep them coming! pictures of your place, the trip to Dakar!