Advertisement

Published: September 7th 2007

Qawali Performance

Qawali Performance

in the underground hall, Shrine of Data Ganj Bakhsh Hajveri (no, I didn't make that up)SORRY, UNABLE TO UPLOAD PHOTOS AT THIS TIME

The alarm screams at six o'clock. I have spent most of the night on the toilet. I pack my bag and fetch a hydration solution. Gabby, my friend's driver pulls up in the BMW. I am lifted to Pir Wadhai, a bus depot located in a slum midway between Pindi and Islamabad. Young children wake from mudbrick homes to a hazy morning sky. I find my seat at the front of the coach and close my eyes. The curtain is closed and I recline. I sip soda and from time to time peer out the curtain. The landscape flitters in and out of consciousness, goat herds, orchards, rice paddies, red faced mountains. A young woman in a black kameez and head scarf wearing purple eye shadow offers each passenger a sandwich and soda. I leave my box untouched. The speakers aren't tuned. As we approach Lahore, the woman's address is an eery sci-fi robot voice.

Regale Internet Inn, Regale Chowk, Lahore. Up two narrow dark flights of stairs, I enter a dank office with dust coated computers and moldy Pakistan posters. Malik, the owner is conversing with his henchmen. I am

shown to the 8 bed dorm. 8 white rectangles flutter as the fan whirls the heat across the sheets like suffering moths. I find an empty mattress in the corner. I feel my pores relax. The fan sends goosebumps down my spine.

Malik leads a group of us in the afternoon to a white Mosque along circle road outside the Old City. We are escorted into the basement performance hall where a crowd of men in robes in pastel or dusty shades sit cross-legged on the floor. A carpet is laid out front row centre and we are made to feel like royalty. We are offered handfuls of sweets. A thin balding man in a grey shalwar kameez and orange scarf stands before the stage dancing, head shaking, right arm raised over head, jumping to the beat without pause. A chubby man in a cap stitched with sequens circles the front row to collect ten rupee notes and places them by the musician seated to the right of the lead vocalist. The musicians have five minutes to inspire the audience's admiration and tips. They must play loud and hard and fast, and sing with feeling. I endure the hard

Pearl Mosque

Pearl Mosque

the one refurbished corner of the Mughal Fortfloor and queezy gut, training my attention on the unique experience. Friends arrive and give each other embraces. Familiar faces smile across the crowd. A man tip-toes through the crowd of cross-legged spectators, carrying a tin cannister strapped to his back and holding a short hose from which he sprays rose water, cooling us with a scented shower. The old familiars signal one another from time to time, stand and approach the tabla player and lead singer and shower them with notes. What a contrast to India balk my neighbors, a young Dutch couple who have been traveling the subcontinent for a year or more. In India nobody drops money. Following the final and most admired performers, the eight or so of us foreigners are lead to a side-room where we are served dhal and chapatti. I have eaten more dahl in four days in Pakistan than in four years in Japan. We climb back outside. The sun has lowered sending long shadows across the white marbled courtyard. Pilgrims wander among the colonnades. Groups gather in pockets to listen to sermons. Crowds of devotees wash at the ablution fountains, chat, relax under the whirring fans. It would seem there are

Mosque of Wazir Khan

Mosque of Wazir Khan

kids clammering for pictures just before their fathers scolded themat most a dozen foreigners in the city and we are watched closely as we make our way through the crowds.

After a twelve hour sleep I wake to a dorm filling with sunshine and the murmur of six fellow backpackers, shades sprawled on white rectangles, flies caught in a web. The rooftop courtyard, a tight fitted kitchen dining and toilet/shower common area, finds me practicing tai chi by the clothes lines. Traffic is waking in the streets below. After a cup of instant coffee, I hail a Chinqi to the Old City. The driver calls out the names of neighbourhoods we weave through, his strong accent muffled by the surrounding cocophany. I enter the fort's forecourt by a small back door cut into a tall wood gate. Beyond the main gate and ticket booth. I discover a sprawling jumble of ruins and a large grass field where young couples sit under the few trees. Succeeding rulers have erected quadrangle courtyards, assembly halls, gardens, baths, resting quarters all within a mass wall several stories tall. The sky plays with a few clouds, an otherwise monsoon sucked dry by global warming. I spend a couple midday hours strolling, studying the

men at prayer, Mosque of Wazir Khan

men at prayer, Mosque of Wazir Khan

I assume the women already had their prayers answeredartifacts in the museums. Tucked into one corner is the Pearl Mosque, the only as yet refurbished building revealing something of the opulence of the 17th century imperial Mughal family.

Badshasi Mosque faces the fort across a broad courtyard of finely detailed pavilions. Fruit, nut and ice cream vendors perch on the grand staircase to the main gate. Street children and their homeless mothers reach empty hands to tourists. The red tiles of the spacious inner court, surrounded on three sides by a long colonnade and facing the mosque's three bulbous domes, are scorching underfoot. I follow an artificial turf carpet soaked in cool water across the court. Inside the high vaulted archways men sit in two and threes chatting or napping under the cool breeze of a generous number of fans. To one end stand two rows of dark handsome men in splendid white shalwar-kameez posing for a photo shoot. I find a place under a fan and re-energize before attemting the bazaar.

The streets are unbearably hot. I produce a tablespoon of sweat with each block. I give up my search for the Golden Mosque, Sunehri Masjid, and grab a cool drink in a shaded hook

of an eliptical chowk, home to jewellers and snack shops painted in blues and greens and ornamented with gold. Down a lane selling crockery and steel, tin and copper kitchenware, I discover the humble entry to the Golden Mosque's ablution fountain, a cool oasis in the market. The raised matted prayer space is cooled by fans whirring above the frenetic chaos of shoppers and shop keepers, taxi drivers and cargo movers. Wazir Khan mosque lies further down the crowded alley. Following the pace of the varied traffic, donkeys, pedestrians, children, women with bundles of purchases, in and out of the sun and the shade of the awnings, I spy the minaret. It is larger and more crowded than the Golden Mosque. Men are gathering for afternoon prayer. I wash my feet at the ablutions fountain and walk to an end of the prayer mats. I attract a small group of young boys, "picture! picture!" I attract the scorn of the men at prayer and move on. I lose myself in the labrynth of stalls selling mobiles and shoeware, linens and pharmaceuticals. I follow strangers streaming into side alleys, hidden and narrowing, descending and climbing, the market continues underground where warehouses

blind date

blind date

selecting prayer beads to metch my shalwar-kameezstock the goods dollied throughout the alleys above. I loop around Moti and Gumpti Bazaar and find my way to Lohari Gate. Beyond the Old City, a wrong turn off Anarkali Bazaar leads me down Hospital Road. No streets bisect it. It takes me an hour or more, several times asking traffic police for directions, before I locate the flower shop on the corner of the alley to the guest house.

A bold move, I fetch a shwarma kebab from the popular street corner stall. It's deliciously unlike dhal. In the cool basement grocery store next door I buy porridge mix and juice boxes. Slowly I am feeding myself to health.

Next morning after a during trip to the bank aboard the local bus and on the back of a kind stranger's motorbike and finally escorted by a mansion's guard, travelers cheques cashed, I return to the guesthouse where an aquaintance is waiting for me. I had talked to him the night before, a local, a clinical psychologist whom I'd been internet chatting with since several weeks prior to my holiday. He is taken aback by the dodgey accomadations. He helps me find a better hotel in

Badshahi Mosque from Cooco's Cafe

Badshahi Mosque from Cooco's Cafe

the latter is owned by the proud son of a prostitute, the five floor home is located in the brothel quarters, Heera Mandithe train station neighbourhood. The price is eight times as much and the bathroom is still grubby, a cigarette butt bathes in the toilet, empty shampoo packets litter the sink, the blankets haven't seen a washing machine in years, a single crooked coat hanger dangles inside the closet and the young man at the reception counter is an asse. But the air/con is hard to beat so we relax hidden from the midday blaze outside.

Afternoon, we catch a motor rickshaw to Coco's Den, a locally famed restuarant located in Heerza Mandi, the Dancing Girl District where centuries old mansions of ill repute skirt the Fort. The owner/ artiste in residence is the son of a prostitute. His paintings of chubby women with pouting lips hang in the downstairs salon. The view from the fourth floor dining hall looks across the walls of Badshasi Mosque. The menu is overpriced. We wander into the bazaar where I order a chapatti and mushy aubergine dish in a small grubby eatery. My guide does not eat. His cook will prepare him dinner at home. We ride a chinqi to Gowal mandi, Food Street. The pedestrian lane is a small slice of Disnelyland. Customers

will not arrive until nine or ten in the evening. As night falls, the chairs and tables bolted to the cobbled street are empty. We order small ceramic bowls of rice pudding from the stainless steel counter on the corner. Kitchen fires line the road. My friend and I discuss reincarnation. For a muslim, he has rather foreign ideas. He was born in Bahrain but loves his mother's native city and would not choose to live elsewhere. He tells me how twenty years back the only traffic plying the old city were horse drawn tongas.

The following day we meet late morning for a visit to Lahore Zoo. My guide sneaks me in for the local fare. Crocodiles laze in a rectangular pool, their eyes and snouts floating atop the green sludge. The big game cages house lions and tigers and bears from China, mountain goats and deer and small gazelle like creatures. I listen to my friend tell stories of childhood visits to the zoo when there were white tigers and the time a man held his baby over the bar and the bear swiped half of it away. Today, families picnic in the shade, small children

clammer on a wee roller coaster. a path leads up and down past cages and cages of birds, ostriches, emu, an eagle, pheasants and peacocks.I drink bottled water continuously and keep to the shade. My friend complains of the heat but I feel alright, slowly adjusting. He belongs to the class of Pakistani who live inside air-conditioned walls. Down Mall Rd, inside the gates to Shalimar Gardens, I am shown to a group of trees where flying foxes nap in the high branches. I look up and discover a colony of fruit bats. Oh, flying foxes, I clue in, noting their large heads. Back in the hotel room, enjoying a siesta and hiding from the intense heat, I watch a few minutes of a cricket match - very strange game - and scenes of a monsoon flood in Punjab.

Late afternoon, I board a bus out front the crowded colonial train station, bound for Wagah, a border crossing one hour east where today, being a Sunday, should prove to be a boisterous flag lowering, gate closing ceremony. At the bus platform, a young man in western clothing introduces himself. He is a student of Accounting. I sit with him

chinqi

chinqi

faster but louder than the old horse drawn tongas of twenty years agoand his colleagues who have arrived almost forty minutes late. My new friend buys me a burfee from a vendor who alights the bus at a slow intersection. Two of his friends are Pakistani airforce pilots, the other two, airforce pilots from Sri Lanka. They are pleased to hear I am Buddhist. We arrive just in time, the last ones let through the gate after managing tickets in a teaming crowd of enthusiastic patriots. I chase after my friends and follow them around the bleachers. They are packed. Beware your belongings, calls my friend. I am swept into the crowd. One foot manages to keep me balanced on the edge of the lower aisle, one arm holds my bag tight in front of me. I haven't limbs enough to take pictures, the other arm supporting me from being sucked under. I've heard of these sort of tragic deaths at festivals in the sub-continest. Pakistan Zindabad! chants the crowd lead by a bearded cheerleader waving a green flag with a white crescent and star. In the facing bleachers sit the women in orderly decorum. I spot a handful of westerners seated in the centre of the affair metres from the marching

food street

food street

Gowal Mandi, Old Cityguards. Dressed in jet black uniforms and feathered turbans, the Pakistani guards attempt to out march their khaki clad Indian counterparts. Beyond the gate a smaller crowd chants Hindustan! Hindustan! The gate is closed, the flags lowered and folded away. The ceremony is over within a half hour. I squeeze my way out before the rush of men above me push their way down. My personal space returned to me, I discover my wallet has gone missing from my pocket. Not all spectators, it would seem, come to Wagah to display their pride in their young nation.

My last morning in Lahore I catch a rickshaw north out of the centre, following the train tracks, past a crowded strip of warehouses unleashing their cargo onto trucks and vans and dollies. The driver crosses the tracks and after asking directions takes me to the end of a dirt road turned giant puddle where the gate to Jehangir's Tomb stands like a film set. Foreigners pay 200Rs entry, twenty times the local fee. I am seldom ripped off in Pakistan, as far as I can deduce. I pay roughly the same fares for transport, whether rickshaw, jeep, mini-van or coach,

the fares depend on the level of comfort and the distance and the remoteness, not the colour of my skin. I enter through the gate, its once elaborate designs faded to the pages of history books. The spacious courtyard, once known as Akbar's Caravanserei lies well landscaped, a hundred metres square with bisecting paths leading to cardinal points where archways lead to further gardens. The flowering bushes leave no scent. A family of tame hawks shelter in a leafless lifeless husk of a tree on the garden's periphery. I skirt a seldom used impromptu mosque, perhaps a stand-by for the gardeners, and wander through the western gate to the tomb of Asif Khan, brother-in-law of Jehangir and father of famed Mumtaz, enshrined in the Taj Mahal. There are no flowering trees or fountains, postcard vendors or families picnicing under the shade of a tree, nor drinks nor balloons nor ice cream cones for sale. It is abandonnned and derelict. A scrubby path leads to a peeled mausoleum where the cool interior is home to a colony of swallows, their droppings scattered across the floor. I relieve myself among the prickle bushes after the guard leaves the yard. Emperor Jehangir's tomb

lies beyond the east gate. What a contrast, gardeners tend the rows and rows of low flowering hedges, other men hammer bricks, others sweep the wrap around portico. The four hundred year old building stands in good repair. The inner sanctuary is like walking into a bowl of pistachio sorbet, cool and smooth, the walls and floor constructed of marble and inlaid pietra dura. The chowkadar continues his sweeping after unlocking the iron gate. He asks for backsheesh when I leave. I look at him with a dumfounded expression and tell him I paid 200Rs entry, sorry.

For all the time and energy spent trapsing from sight to sight, enduring the heat, suffering dhiarrea, pick-pockets, the historical landmarks leave little impression. Perhaps I have seen too many bollywood flicks and am uncontent less there is music playing, children scampering, parents smiling fondly after, everyone dropping the ir chapattis and forming an elaborate dance number. Traveling from A to B, from awkward blind date to Mughal relic, what lies between, the side streets and strangers, spices and traffic, smiles and surprises offer me inspiration to travel on.

The return trip into town takes longer but far cheaper. A young

man helps me board a crowded rickshaw by the tracks and we alight at a junction where we board a bus and wait for passengers to fill it. We climb onto a highway overpass. I try to follow in my guidebook. The young man alights not before telling a neighbour where to have me get off. I can't recognize the route. After a bend, we enter my guidebook's map. I let off at the shrine of Data Ganj Bakhsh Hajveri. A sudden gust of wind lifts a sand storm across the crowded chowk, filling eyes, spraying butcher shop's meats, their little fly swatter fans useless, filling the juice shops and the curb side trollies of fried potatoes. The sandstorm follows me up Lower Mall where I ask a traffic cop for directions to Lahore Museum. Wait one moment, he gestures, still busy directing traffic, somewhat dazed in the billowing dust. He calls his partner over who tells me to climb aboard his shiney motorbike, my hand within easy reach of his firearm. Trust between strangers is a beautiful thing. Housed in a brwon brick with off white trim domed roof colonial building, Lahore Museum displays artefacts dating from Prehisory to

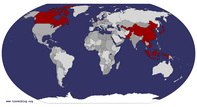

Lahore Museum

Lahore Museum

when you think of Pakistan, what first pops into your mind?the struggle for Independence. The latter exhibition is a collection of old firearms and armour. the former a series of dimly light glass cases holding pottery and stone tools. The largest halls containbs all things typically Islamic, copper urns, mosaic tiles, carpets, robes, old Korans. In the central hall hang my favourite, miniature Mughal paintings and in the back gallery stone busts of Indo Aryan boddhisatvas survive from the Gandharan civilisation.

Advertisement

Tot: 0.048s; Tpl: 0.018s; cc: 10; qc: 25; dbt: 0.0229s; 1; m:domysql w:travelblog (10.17.0.13); sld: 1;

; mem: 1.2mb

Leslie

non-member comment

painting

Kevin: you paint a wonderful picture in words.