Advertisement

Published: January 31st 2009

Lihat Sawah, Sideman

Lihat Sawah, Sideman

Gunung Agung emerges in the distanceAt 4am a bluebird pulls up to the gate. For the next half hour en route to Juanda, as the meter ticks away, Teghan recounts the previous late night out when she’d met with a few friends at the Lido to wish our collegue Dave farewell. She didn’t drink too much and left around midnight. She noticed a motorbike pull into the bar’s car park only to turn around and exit just after her. The journey across town follows well light avenues with ocassional traffic. But pulling into our neighbourhood in east Surabaya, a less travelled road obscured by tall tamarinds, the motorcyclist pulled alongside Teghan and tried to snatch her purse containing her plane tickets and a considerable sum of cash. The purse strap wrapped around her neck did not snap as the thief had no doubt expected. Teghan was pulled sideways, her scooter too, until it skidded out from under her and she tumbled across the pavement, her hips, knees and ankles bruised and bleeding profusely. My friend reapplies bandages to her cuts while we wait in an airport diner speculating as to why airport shops and restuarants charge such exorbitant prices. She hasn’t slept at all, suffering shock

and unable to clog the bleeding. She shares something curious with me, how she knew instinctively that something bad would happen to her before she returned home and feels in spite of this all the more determined to leave Indonesia. Crossing the tarmac at Ngura Rai, Teghan begins sobbing, overcome by the physical pain and the trauma. We hug good-bye and I watch her limp, leading her suitcase toward the transit lounge. Life can be awkward and unsettling for a Westerner in Surabaya. I am so ready for a holiday.

Saturday. Samanila. Sally won’t arrive until Monday. A weekend of relaxation and long awaited promiscuity lies ahead. I book into a quiet air-conditioned room in

Legian, a block off the beach on Padma Utara, and breakfast at an open-air café. My housemate from Brisbane scorned Bali and Lombok, said the islands had been ruined by too many ignorant Aussies with little experience abroad. He’d finish his rant impersonating one such undesirable tourist. Sipping my kopi Bali, I think I hear Don sitting at the next table having a laugh with me. A man’s voice far louder than necessary completes every other phrase with the f-word and colours the words

Bakso

Bakso

Sally's first taste of Warung farebetween with bloody this and bloody that. Midday, following a nap, I traverse the neighbourhood’s sidewalks overgrown with revolving racks of sunglasses, seashell belts, profane stickers, hushed voices selling marijuana, endless clusters of young women, “massage, you want massage, mister?” The sky grows over-cast, the wind tosses a torrent of showers at angles my umbrella cannot endure. A few young surf instructors huddle under low trees, other entrepreneurs fold up and pack away their lounge furniture. A table stands at the water’s edge displaying an array of fascinating seashells, luminous in even the faintest afternoon light. An intricate kite constructed of plastic dowels and rainbow coloured nylon ribbons, a double masted ship, sails in the strong breeze.

Seated at an internet café, my stomach begins to grumble and churn. I race back to the hotel with a few bottles of Bintang and spend the next few hours orbiting the toilet. It’s all good though, I’m on holiday, I’ve air/con and cable, and a good novel, The Painter of Shanghai. A sticker pasted across the paperback’s front cover reads, “If you liked Memoirs of a Geisha…” How tacky, imagine you’ve spent how many years researching and writing and struggling to

have your story published only to have it advertised as an alternate version of somebody else’s story. The heroine in Shanghai is likewise a culturally skilled lady of the night. However, she acheives her freedom early on in the story and shows herself to be a far more assertive and independent feminist than the Geisha. Beer doesn’t cure dhiarrea but enjoyed nonetheless late morning it reaffirms my holiday’s priorities. The sun is out and children’s laughter rises from the hotel pool. Unrushed, uncommited, I finish my novel and a surprisingly tasty bottle of BaliHai.

The crowds have returned to the beach, volleyball matches where the muscle bound all too consciously flex as though the game required superhuman strength, football matches, dark young men, shirts versus skins, scramble in the soft sand, their tracks, a confused play by play are erased with the tide. Surfers ride the waves and fall in photogenic explosions, they wander the ocean’s edge, their long shorts, a curious fashion, are hung low to reveal a sexy set of buns. Smooth dark skin is my favourite place in Indonesia. Dog walkers and joggers, accustomed to the piles of rubbish and dead fish brought ashore, enjoy the

fading colours of a setting sun. People watching.

Monday. Miscommunication. Midmorning monsoon. After breakfast, the hotel’s concierge arranges for me a cheap motorbike rental; an empty tank, loose, floppy sideview mirrors, a defunct spedometer and speeds above 30 km/h require fourth gear. There’s no gear indicator. I communicate my anxiety that this will lead to an accident. Nyoman, the bike owner, assures me I’ll be fine if I use my intuition. If I used my intuition, I’d rent a better bike. The rain falls in a thick sheet blinding my progress. The helmet is without a visor. After asking directions a few times, I arrive at the airport an hour later than agreed, hoping Sally has been tied up in customs or baggage claim. The arrival screen mentions no flights from Sydney, not until 14:30. I try calculating her flight; time zones and further speculations. I explore the departures lounge, purchase a pastry and orange juice, withdraw funds from the ATM and return to the arrivals gate to study its demographics, an equal percentage of natives and foreigners, the latter composed primarily of Australians and Americans, followed by Dutch and French. Surreptitiously undressing a slim, six foot, broad shouldered

young Indian, Sally appears suddenly and miraculously from behind a chubby couple. “Kevin?” “Sally!?” She’s far slimmer than her old self back in Japan, the bone structure in her face more defined, and her hair’s cut close to accentuate her cheek bones and jaw line. Strange, but you can tell when a woman’s good friends with her hairdresser. Sally explains she’d flown via Adelaide, already a long journey from Canberra via Sydney.

Australians learn Bahasa Indonesia in public school. Sally laughs listening to me speak with the taxi drivers and security guards. “Nama saya Sally”, she jokes, recalling her lessons from all too long ago. We return to Legian and check-in to Three Brothers, an upper mid-range resort set in extensive lush grounds disguising the lack of service and security. The garden’s caged monkey is more secure than our room, which someone attempts to break in to while we’re out, leaving the double doors half open.

Our conversation, animated, over-excited, non-stop, and somewhat disjointed, like that of lunch hour highschool girls, leads us from Legian to Kuta to Seminyak, from one convenient shop to another procuring cold bottles of Bintang. Sally recounts her surgery, paints a few terrible scenes

Cool Cat, Sideman

Cool Cat, Sideman

a happy wander through the 'sawa'in her art classroom, shrugs off her less than perfect romantic liasons and entertains me with tales of her sister, Oompa, and their household’s antics. Beyond a group of gay volleyballers in wee speedos, we reach Zanzibar’s just as the heavens let fall a deluge to block the sunset. Acompanying a free appetizer buffet, Sally treats me to cocktails as I catch her up with the often synchronis ease and hardship of a bule’s ever enlightening stay in Indonesia. Late evening we make our way along Raya Seminyak to a new Belgian restaurant/ jazz bar I’d learned of while flicking through Garuda’s on-flight magazine. I savour a bottle of Hoeggarden, Sally, a goblet of Leffe Blonde. The creamy pasta and heavy meat dishes have a drowsing affect. Sally’s drunk and mesmerized by a pair of overfed potbellied goldfish floating upside down in a pond next to our table.

Tuesday. The next day and until vacation’s end I will forget what day it is apart from the obvious holiday reminders but today is Tuesday and we set off eastward, two big bules with two big rucksacks pinned aboard an ageing yamaha, on an adventure I’ve somewhat planned. We have no

hotel bookings but outside the tourist traps of Kuta/ Legian and Ubud, few visitors roam. I’ve taken the slowest route across Denpasar. Hot, congested and fumy, Sally’s impressed with my traffic skills, as we manage the obstacles native to any mid-sized Indonesian city. She takes it all in, the noise and colours and carbondioxide. It feels good that I can do this for my friend, that I can show her Indonesia, that I can feel like it’s my home and that I have learned something here. Reaching the first series of black sand beaches of East Bali, we head inland climbing a lush valley of terraced rice paddies through which descends a photogenic Sungai Undah. Three hours outside Kuta we reach the village of

Sideman (a plugged nose pronunciation of cinnamon) and locate our guesthouse of choice, Lihat Sawah. Sally proposes an afternoon stroll among the paddies. A gushing river spilling its cool charm over long ago fallen rocks provides the locals a pleasant open-air bath. Nude figures soap themselves a polite distance from the bridge where Sally and I, squinting but failing to improve the view, descend to the river-bank, carefully hop across the stones to mid-stream, peel down

Sideman

Sideman

a river runs through it where the locals bathe NAKED!to our skibbies and immerse ourselves in the local culture.

The guesthouse dining area with views across the valley, serves reasonably varied and tastey fare, cold beer and my favourite, arak madu, palm wine with honey. We avail ourselves of its amentities late into the night, reading, sketching, dining and soon sharing a most stimulating conversation with three other guests. Tom, from Adelaide, has recently made the big move to his newly constructed home somewhere south of Sideman, and has brought his wife and children too. He pours us all a glass of Johnny Walker Red and with a second bottle keeps our glasses wet. When these run dry, Monique, a greying-blond from Deventer who’s working for a NGO in Port-au-Prince, presents us all a generous taste of Haiti’s best Rum. Her partner, Ronald, is French-Canadian and has worked alongside Monique in several developing countries. They are in Sideman at the bequest of Tom, whom they’ve met in person just today after a couple years of cyber-acquaintance. Monique and Renaldo are thinking to soon retire in Bali’s diminishing backcountry. A loud chirrup errupts from near Sally’s and my room. “Have you seen the big gecko?” Tom asks. From over

twenty metres away, it’s clearly the largest I’ve ever seen, and upon closer investigation, measure his body over a foot long and its head the size of a tennis ball.

I find my dinner companions interesting. Sally has spoken considerably with Tom and later admits she finds the man rather pompous. “He is loaded,” she adds, "in both senses of the word." I ask of their opinion,

“How do you live with yourself, with your first world priviledged lifestyle in a third world environment? Why do you choose to live in a developing country?” Tom explains about his future endevours to improve the life of the villagers in his new community, how he’s employed several in the construction of his home and how his wife plans to introduce goats in the village, to produce milk and cheese, and she intends to train several of the locals in this industry and keep them employed. Monique shares more stories of her time in Angola and Nigeria, Khyrghistan and Colombia where over the past decades she has laboured to improve the local standard of living, improving sanitation, hygiene and basic awareness of one’s health and one’s rights. She is usually treating uneducated

communities whose beliefs we would consider backwards and superstitious. Ronaldo lets the question roll around in his head a while. “It’s very abstract,” he contends. He sums up his point in one word. Unfortunately, I’ve consumed far too much booze to recall his wisdom the next morning. None of them, however, consider relinquishing their lifestyle. They believe that by maintaining their status and contributing to the third world community to better their lot will do more to improve things. Personally, I’m unconvinced and believe the future might be a better place if more westerners learned to lead simpler, less consumptive ways, and learned the benefits of leaving a far smaller footprint.

6a.m. Christmas Eve, Sally rustles me from deep sleep. I’ve promised her an early morning hike. Hungover, sleep-deprived, eyes half shut, I stumble down the road, across the river and locating a mossy staircase up the far hillside, we leave the road in the general direction of a hilltop temple. Backtracking a couple of misleading dead ends, we soon arrive in back of a quiet village. The path, following through dark undergrowth, skirting a row of houses, leads to a wide and challenging staircase, a slippery moss covered

final ascent where a troupe of villagers meet us, approaching from another entry point. “Donation.” “Donation,” several of them cross our path and hold out their hand. How many tourists must fall prey to their scam? How many tourists provoked this scam in the first place? “Ma’af, Pak, ruppiah g’ada.” But they stand next to us unwilling to pass up easy money, their presence causing my friend untoward anxiety. The temple’s not much, a bamboo or rattan skeletal structure with no detail, no artisitic work, amid a flat surface of ground, ten metres square. The views to the southeast and to the north might otherwise be sensational but a low grizzly blanket bathes the slopes in a hushed and dark anticipation of heavy rain. We trod back down the slippery stone steps and through a slumbering village startled more than once by unleashed dogs.

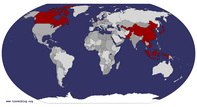

On the map

Pura Besakih, high up the southern flanks of

Gunung Agung, appears rather close to Sideman. The country roads wind along the rivers and terraced rice paddies, climb and fall, heavy trucks gearing down, slow traffic, and the complete lack of road signs makes for a far longer journey than anticipated. At a

Lihat Sawah

Lihat Sawah

Gunung Agung emerges among the cloudsT-junction in what appears the middle of nowhere, I break and in an instant am surrounded by four men, requesting I pay an entry ticket to the temple. They’ve no uniforms, no badges and there hangs no sign as to a ticket booth or a marker indicating whether there exists a nearby temple. “No thank-you,” I insist but one man has stood in front of me and grips my bike’s handlebars. “If I need to buy a ticket for the temple from you, I will come back.” Either they don’t understand first conditionals or are unwilling to compromise. “Fine, we don’t want to go to the temple.” I signal right, rev the engine and start to move, the man jumps out the way and I steer down the hill making a U-turn at the nearest opportunity and accelerating uphill past the gang of unseemly ticket agents to where presumably stands Pura Besakih. At the top of the slope several young men lounge on motorbikes in a disorganized parking area across from a small wooden hut where one of a group of older men calls, ‘sarong?’ “Yes, we already have sarongs.” “Ticket?” “Yes, we’d like two tickets.” “No, you must buy

Sally the tourist, Pura Benesari

Sally the tourist, Pura Benesari

high atop the southern slopes of Gunung Agunga ticket down there.” He points back towards whence we’ve just come. “Didn’t you see the men selling tickets?” he asks. A few expletives later I’m back at the T-junction, keeping my cool as best as possible, and having to kiss ass with a group of middle-aged men whose pride deafens them to my slow and simple Indonesian explanation that their ticketing sales approach appears very suspect. They have no patience for uniforms or badges or signs and consider my explanation and behaviour a farce. Most foreign tourists to Bali do not venture far beyond the shore. Their conception of Indonesia is consequently rather deficient in experiences. I like to think I’m a better person for having endeavored to understand this young nation and its peoples. Nonetheless, this latest experience illustrates the great cultural divide that remains.

Had Sally or I shown greater awareness, the debacle may have served a prescient warning of the dismal proceedings that lie ahead within the temple grounds. We wander up the approach road, lined to either side by a desolate row of warungs each displaying a glass case of meat dishes long since cooked and bursting with bacteria, interspersed with the odd souvenir

Pura Benesari

Pura Benesari

admittedly disappointing - tourism has all but killed the Bali's major temple sights of spiritual worthstand selling wooden windmill-like characters, kites, and postcards, bypass potholes filled with muddy rainwater providing drink to a pack of mangy rabid-looking hounds. All that’s missing is tumbleweed. Perhaps a dozen native pilgrims can be seen praying among the quiet pillars of brick and stone statuary while half as many foreigners amble about trying to make a worth while visit following what must seem an unwarranted half day’s drive from their bechside resorts in Kuta. Every few yards, the hand of a wee wide-eyed child or a slumped old woman extends, asking charity. Younger more enterprising women sell peanuts or other refreshments to a high-season crowd that has yet to arrive. As a sidenote, I advise travelers to heed such precautions as listed in the LP concerning Pura Besakih: “an unholy experience”, “scams and irritations”, “dissappointing”, and ask yourselves, did you come all the way to Bali to see temples?

Rain clouds from the south interrupt the early afternoon and force Sally and I to pull off the road into a village market. I introduce my friend to a few well-known delectables:

babi guling, sate kambing, urap-urap, tempe and

nasi pecel. Thankfully, my friend is comfortable eating in a

Sal & Cool Cat

Sal & Cool Cat

and the grandest of temples at Pura Benesari: prepare to be disappointedmarket full of curious onlookers and her stomach is strong enough to sample the local street fair. Locals in these parts seem to enjoy a fun game with foreigners lost in the backcountry. On our journey back to Sidemen, I stop more than a dozen times to ask directions but three out of four respond in complete gibberish, the most memorable’s a line ending, “Bali ho!” We find ourselves backtracking through a strangely familiar neighbourhood when it dawns on Sally that we’re back at the hilltop village overlooking Sidemen. It’s a steep drive into the valley where we stop before a small tile factory down the road from the guesthouse. A friendly woman from the Netherlands invites us inside, tells her story how she came to live here with a local, leads us through the warehouse, demonstrating each step of the tile-making process and finally into the backyard where an array of beautifully painted designs are drying on a series of tall racks. Most of her business is exporting to America and Europe.

Christmas morning, Sally presents me with a bright red stocking jammed with goodies: an ink well; a pen with several nib sizes; a sketchbook and a box

of Christmas Questions, the latter we deem a most dreadful invention, a conversation starter the likes of which only a televised Martha Stewart might optimize. Sally and I, packed up, squeeze onto the bike and head north-east skirting the southern slopes of Gunung Agung, admiring its conical peak in a perfectly clear sky and follow a circuitous and leisurely drive along a string of pleasurable hamlets basking in a tropical sunny day. Views of distant Lombok, of Gunung Rinjani, and of Nusa Penida whisped with cloud, appear and dissappear across a blue horizon. The road climbs from

Amlapura to nearby

Tirta Gangga where we book into Puri Prima. A pleasant block of rooms nestled on a cliffside garden overlooks a broad sweep of terraced rice paddies, sewn with a confusion of footpaths and a scattering of palm and bamboo huts, climbing towards the peaks of

Gunung Lempuyang and

Gunung Seraya five kilometres distant.

We put our old bike’s gears to the test attempting the climb to

Pura Lempuyang, nearly falling off several times popping it into first gear along steeper sections and tighter hairpins. Reaching the last carpark on foot we’re promptly reminded that sarongs are required and can

be rented for a mere 20,000Rp/ each, or roughly twice the cost of our motorbike. Unwilling to pay their absurd fee and loath to put up with anymore Balinese entry ticket b.s., I explain that my friend and I won’t venture inside the temple proper. Scores of pilgrims, long trains of families, young and old and inbetween, all dressed in layered sarongs and Indian-inspired prints and colours, climb or descend the long procession of steps atop the mountains high crest. Through the branches either side of the path appear views to the northeast and southwest. Family members pause to catch their breath, smile as we pass, impress relations with their English greetings and odd comments to the foreigners, nobody seems bothered or seems even to notice that we’re not wearing sarongs. Hiking a mountain in a sarong would seem a strange custom to appease the gods. As Sally and I reach the opening of the hilltop temple, a chorus of cheers and hoot calls erupts. Balanced on a viewing platform’s handrails two monkeys are fast at it.

There’s nothing to do but relax, watch the silly beasts clampering about the branches, cleaning each other, rummaging through the offerings for

Gunung Agung

Gunung Agung

from the southmorsels, and gaze across at the vast easy slope of Gunung Agung where the clouds curl like surf.

Lights out, our tummies satiated on delicious barbecued fish and one too many bottles of Bintang, something the size and weight of a mouse scurries across my blanket. With a scream, the lights are back on. Several oversized insects are kindly shown their way out, except for a spider the likes of which I’ve never seen before who meets the soul of my sneaker before I may sleep reassured. A lone lightbug twinkles above my bed.

One more day in Bali and one more tourist sight: the water palace, a short walk from our guesthouse. A mid-twentieth century construction completely devestated by Agung’s eruption in ’63, and rebuilt surrounded by a small enclave of over-priced eateries, the gardens offer a pleasant morning stroll finished with a cool dip in the pools. A lavish guesthouse overlooks the fountains and spritley sculptures. Sally and I splurge on brunch, seated in a gazebo above the lilly ponds, nibble at pastries and jams all the way from New Zealand, while sketching the exotic plantlife.

The coastal highway is a comparatively easy-going drive and

Gunung Lemuyang, East Bali

Gunung Lemuyang, East Bali

from Puri Prima guesthouse, Tirta Ganggavoid of traffic except for a bottleneck of tourists’ rental cars in Candidasa. South of Klungklung, we veer off the highway to explore the blacksand beaches and isolated temples. Groups of men and women dressed in near rags, tucked inside hats and handkerchiefs wrapped round their faces work under a brutal sun, a salty wind whipping at their backside, hunched, they dig in the tough surface of stones, probably earning a few dollars from a landscape company. A woodshed warung kopi sagging against tall grass bordering the beach serves small snacks and refreshments. Five little frenzied chicks chirrup for their mum, a hen hidden out of view beyond the counter, the far side of an ominous tangle of human feet.

Sal and I return reluctantly to the wheeze and congestion of South Bali and return the motorbike after deciding on a hotel in Legian tucked down a quiet gange. We discover a warung on Legian’s highstreet serving delicious fried catfish, order two portions pecel lele di pungkus and catch a cab for Pantai Bintang, a lesser known beach behind Petitenget, popular with middle-aged gays and their under-aged money boys. The partons all seem to know each other, a small

relaxed community of mostly Europeans who live several months of the year in nearby villas and convene at this popular open-air bar to soak in the last rays of sunlight. Several drinks later, a sunset walk down the shore, Sal and I are seated on the verandah of a Greek establishment on Jalan Oberoi, having fun with the passing vendors, testing nylon tattoo sleeves and other plastic glow in the dark trinkets. We order too much: a lamb souvlaki, saganaki, and pita with homous and tzatziki, but nibble and drink late into the evening, drunk and somewhat annoying to the sober diners seated within wide earshot. The evening concludes up the road where a few last drinks in a stylish new gaybar find me waltzing with a drag queen in a long black robe, mumbling, “You’d better lead.”

Advertisement

Tot: 0.104s; Tpl: 0.019s; cc: 14; qc: 23; dbt: 0.0403s; 1; m:domysql w:travelblog (10.17.0.13); sld: 1;

; mem: 1.2mb