Advertisement

Published: October 18th 2007

fried fish, Dir

fried fish, Dir

fried fry fry fry fishI take a seat in the sweltering mini-van's third bench next to the window. There is not the slightest breeze in the depot. Three men from Gudjarat, a traditional community in the Punjab suffer the bench with me. Pakistanis from down country are darker and chubbier than those in the north who could easily pass for caucasians. They are four traveling together, their older friend in the next bench. They are advocates. I assume they mean lawyers. From Timargah, we climb north along the Panchkora River. The valley narrows and the slopes grow denser with pine trees. We arrive in Dir a little before sunset. In five hours I've traveled 160km. The market slopes down from the bus station to Dir Hotel. Exhausted but responsible for 25kg strapped to my back, I brace myself for the shopkeepers' stares. I discover a quiet green refuge awaits me at Dir Hotel. The lawn and gardens lie sheltered beneath two trees each over four stories tall. I climb back up the bazaar and duck into a wood shed behind a roadside stall where a man in a bushy moustache fries oily river fish. I fetch a bag of cashews and a bag

of pistachios, luxuries back home, and retreat to the hotel's oasis. A peahen stalks me as I sit at a table in the garden taking evening tea. As I light up a charras, a young father and his daughter sit with me and practice their English.

Back on the lawn early morning to practice tai chi, the peahen stays clear of my swinging arms. I order an omlette and toast before gathering my things for the jeep to Chitral. Dir is not a place to stay long. Dir is a transport junction, a jumping off point. Not so terrible a distinction considering the far more numerous towns across the globe one would consider neither destination, junction, nor detour but never consider at all, like my home town. Ten kilometres out of Dir, the road is unpaved. My face is glued to the window, my mouth and nose covered with my shalwar-kameez against the cloud of dust sprayed from passing trucks. We start to climb the switch backs passing brown remnants of the northern hemisphere's southern most glaciers. At Lowari Pass our jeep is given a quick look over before the officer lets us through. Magically, trucks find space enough

to pass descending a series of steep switchbacks down the north face. Beyond yet another checkpoint the paved road meets up with Chitral River. We pass Naghar where a century old fort is still occupied by descendants of the Mehtar of Chitral. I can't actually see them but I trust by my guidebook that they are the ones charging travelers an arm and a leg fo a night's stay. The river flows broad and brown raging south.

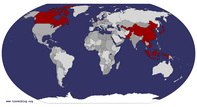

Chitral The Hindu Kush. Mountains rise to the west, the south arm of the great range hiding Afghanistan and the Durand Line. In 1893 the Pathan Emir of Kabul sought to kill or convert the Pagans of Kafiristan. Many refugees settled in Chitral district safe within British India. Known as red kafirs, they built simple villages in the upper valleys of the Kalash. Ironically, they soon converted to Islam of their own free will while the Kalash, with increasing notoriety in the western media, have retained their traditions and Indo-Aryan polytheism. Exhausted from the five hours pinched between the window, my neighbor and the bench, I check into Al-Farooq, directly opposite where the jeep comes to rest in the market. In

the late afternoon sunshine I stroll the bazaars and wander to Shahi Masjid, a century old onion domed mosque. The inner courtyard is empty, a smooth tiled oasis bathed in blue reflected from the overhead tarps. I try to meditate but it feels sacreligious so I give up. In the evening I dine on various dishes in the shops, some fired potato, a spicy bowl of chicken and corn soup, samosa, finished with a bowl of sorbet in the corner store. On the hotel'srooftop I smoke a spliff and offer a few drags to a fellow from Peshawar. I watch for shooting stars, thinking about my childhood summers in the Okanagan under the same sky. The silhouette of a half naked man catches the corner of my eye, one leg folded over the other bent knee as he reads in bed. The Peshawari fellow invites me to sit with his friends on the lower balcony. I slice a mango and eat its juicy messy fruit. The advocates from Gudjarat invite me to their room for a game of cards. They teach me decati, robbery at gunpoint. Conversation had been out ruled. Anything political or religious from their mouths seemed formed

by rumor or the back cover of a limited publishing. I mentioned to them something I'd heard in passing, that a supposed secret intelligence file had surfaced in America showing a map of the world in 2015 and there was no Pakistan. This led to confrontation. We made a pact, said one, not to discuss anything work related. I learn instead about their families and community. All of them are married, three of them with children, the fourth expecting. Although the community is Muslim, it is a caste society. They are djats, members of the farmer caste, landowners. They seldom marry outside their castes.

Kalasha Valleys After failing to secure any information on trekking around Chitral from the town's various agencies, all closed. Gyohar, a tall employee of the hotel suggests I talk with Taj, a well known guide in Bumbaret Valley. In Attaliq Bazaar, I hop a jeep to Kalash. Five other foreigners are waiting for a lift when I arrive, two Danes, an Irishman, an Aussie and a South African. They'd all met in Peshawar. The jeep turns off the highway and crosses the river on a long suspension bridge before climbing the west bank of

Chitral River. The road is covered in thin sheets of rock, flaked off the cliff face. We pass throug a sleepy market, Ayun, and continue to climb the narrow Ayun River valley to the region's checkpoint, a wood hut standing alone in the rocky canyon. After each of us has signed and paid the entry fee we continue up Bumbaret Valley, the central and most touristed of the three Kalash valleys. I am the first to hop off, in the small village of Brun where I check in to Ishpatta Inn. The others continue to Krakal where the jeep and driver belong to.

A Japanese fellow sits in the small apple orchard in front of the guesthouse, the same man who's sexy silhouette had graced the hotel's rooftop in Chitral the night before. He is quiet and looks well-traveled. He and I are the only guests it would seem. The hotel manager is a tall, broad man dressed in a shalwar-kameez and a katosh, a wool cap rolled up at the sides. His manner is abrupt, friendly one moment, sarcastic or rude the next. Jabin, a young assistant with a soft voice and big chai brown eyes leads me

on an afternoon walk up the valley. The dirt track is lined with walnut trees and the odd house or guesthouse. Cornfields hug the hillsides and spread as far as the riverbank. The Greeks have invested in the Kalash Valley, supporting the idea that they are descendents of Alexander's soldiers or the later invading Parthians. Plaques written in Greek commemorate a new two story stone and wood museum, a similarly designed school house and a

bashali where women must stay during their periods and pregnancies. The men in Kalash dress like the muslims elsewhere in Pakistan but their wives and daughters wear black dresses sewn with with red and orange and yellow stencilled trim. Kalash translates as black dress. In Krakal, the largest village in the valley, I am introduced to a young man named Golum. Has he seen the Lord of the Rings I wonder. His English is quite good, an American accent. He has been studying on a scholarship in Thessaloniki. On his holidays, he and his friends travel interrail to Germany and Switzerland. We are seated in a small bare room overlooking the street that runs through town and the only general store, a small recently built

wood shack where the path off the road leads into the village proper. His cousin pours us chai before returning to her sewing. Across the hall is a doorway into a spacious kitchen where a cauldron cooks on a fire on the far wall. Compared to Europeans, says Golum, the Kalash are very modern, very liberal minded people. We can discuss anything. And when I'm hungry I can go into anyone's house in the village and sit at the table and be served. Our conversation continues until the rain slacks. Jabin takes me further up the road to a graveyard. The wood coffins lie above ground, many lids open and bones scattered among the trees. At the head of the valley lies a Nuristani village of the red Kafirs, the Afghan refugees of a century ago. A mosque constructed of wood and painted white with green and blue trim stands next to a pond where small trout from the nearby hatchery swim next to a yard with a perfect little white house, a cow munching on the grass. Across a footbridge lies the village proper, a stack of long wood homes supported on stilts, the floor of one yard the

hunter, temple wall painting, Kalasha

hunter, temple wall painting, Kalasha

The Kalash are animists surrounded by Muslim societies. In Bumbaret valley stands a temple in the main village of Krakal, a dark hall off limits to the women folk. Each year the walls are painted anew with scenes of daily life.roof of its neighbor below. There are no women visible. There are no black dresses.

The Japanese fellow, I guess correctly is 35 years old. His name is Nobuyuki on the registrar but he tells me to call him Nobusan. He has been traveling since one year, in Australia, South East Asia and India. He will continue for another year and head to the middle east via Iran then into Africa. He watches his budget carefully. He cooks his own food. He has grey hairs, especially his sparse beard. His teeth are every colour but white. I find him attractive though, perhaps his energy, a calm piece of japan. Before traveling he tended bar in Sapporo. He and I spend the next day together wandering the orchards, the tall corn fields and canals of lower Bumbaret. There is no indication of private property or signs warning against trespassing. The footpaths disappear into the river or vegetable patches or into the homes. Friendly old women in wrinkled smiles point us in the right direction. "ishpatta Baba! Ishpatta Baija!" how are you sister, how are you brother. One path brings us to a shaded yard under the canopy of wide bushy

trees scattered with family members. I approach cautiously, unsure how much a fright I'd be to the grandmother. Nobu is quiet behind me. Naturally, I've taken the lead on our hike. A man in a wool cap sitting on a bench under the covered porch calls down the yard to me, "come, come, welcome to my house." We find our way across the creek, dodge cow pies and chickens and take a seat next to him. Grandmother peels fruit. Grandfather doesn't look to be doing much. The young children keep a safe distance. "I am a teacher in Krakal." His wife is dressed in the traditional black frock, seated on his far side and holding their baby in her lap. One of the girls climbs an apple tree and shakes a few from the branches. Thud. A plate of them is rinsed and placed between Nobu and I. After British travelers, Japanese are the most common foreigners to Chitral District, reports a chart hung in the Foreigner's Registration Office in Chitral. Over a hundred each year compared with a dozen or so Canadians annually. I peel an apple, its skin falling in pieces to the dirt below the stool. A

couple chicken squabble behind me next to Grandmother. The teacher is interested in Nobu's Japaneseness. Nobu carefully peels an apple, the skin falls slowly in one long piece on to the plate next to the other fruit. I show the man a Kalasha language book I'd received from another teacher in Krakal. He reads aloud for me how to pronounce the alphabet. The rain shower passes. Nobu and I continue our walk. He bows, hands in prayer position held before his chest. I've never seen any Japanese greet foreigners or each other this way. I feel ashamed but can not bring myself to imitate Nobu, however honourable his actions seem. We criss cross the river back and forth, upstream and down, find a perch on some rocks and share a charas, then follow the canals into the hillside and bushwack through fields of giant corn stalks.For several weeks of the summer, the Kalash people hold a celebration. In Krakal, every other night they gather in the evening in a square courtyard where the young women dance. That evening, Nobu and I walk up the dirt track in the dark, our headlamps navigating the mud puddles. The Milky Way spreads overhead.

above ground cemetery, Krakal

above ground cemetery, Krakal

evidence of Alexander the Great's contact with the Kalash comes from a journal kept of his conquests, in which it is mentioned that in search of fire wood they cut open the coffins, not realizing what they were!I can imagine the earth, a tiny ball lost in one of the millions of galaxies all swirling. How naive to think we are the only intelligent life forms. It is a kind of romantic night. It takes a while to reach the village. In the dark there are no milestones, only empty space and the inevitability that having left A one will eventually reach B. I follow the footsteps I'd made with Jabin the day before and guide Nobu up the path to the courtyard following the sound of drumming. Men stand around chatting, most of them tourists from Peshawar or Punjabi. There are no lights, no decorations, no master of ceremony, no trinkets or souvenirs of food or drink for sale. In the dark a camera flash occasionally lights the ceremony, where five or six teenage girls stand close together, arms held across their neighbor's shoulders, side stepping in time, their dresses folded into one another's, baby steps, circling around the ring, creating the ring. Aaaaaah, they half sing, half hum in unison. It feels ancient this ritual. They circle around the drummer and a group of young man gathered in the centre chatting. Another centipede in black

dresses with red and orange and pink embroidery begins to circle, then stops, spins in place, laughing in the flash of my camera bulb.

Nobu and I, as arranged are packed and ready to leave next morning by eight o'clock. The proprietor had discussed with me the day before the fees for guide and porter to help with the Donson Pass Trek. He had talked about food and supplies, taken out a huge gas tank and said we'd need to take it along. Preposterous! A two day trek would amount to more than 50$US, absurd for an 'open zone' in a touristed corner of the country. I know the road to take into the mountains. The morning is cool and overcast, a slight sprinkle. The valley narrows, climbs a way, boulders slow our pace. At a fork in the path, leading up two unseen paths, I ask a shepherd the way, his goats head butting each other playfully. "Passuwalla?" I ask, "Donson Pass?" He points left then right answering my question. On my map, the two lie next to each other, the pass leading to the pasture where we will stay the night. The left seems less steep and

village of the Red Kafirs

village of the Red Kafirs

inhabited by descendants of Afghan refugees from the late 19th centurya little clearer to follow. Our bags take on greater weight as the hillside grows steeper and we climb higher, the pace slackening. Soaked in sweat, I look ahead to a point 100m beyond and make that my next resting goal. 100m takes longer and longer, the slope rising 45, 50, 55 degrees. I climb on all fours, my balance taken away as my backpack slips over my shoulders. 'This isn't trekking,' yells Nobu, 'this is rock climbing!' How he can manage in trainers and an old metal frame rucksack is beyond me. Rocks grow fewer and then plants grow fewer. I struggle to find a hold, sending rocks cascading with each step. It's impossible this is the path. The guide would never have lead us this way, I admit to Nobu, declaring defeat. You want to climb down? he asks. I leave my bag and scramble up under the dead pines and bramble bushes blocking the view. Fifty metres ahead the slope relaxes to 45 degrees. It looks possible to continue this way. I find Nobu and we reach the top of the mountain together. The view back across the valley is blocked by the trees but the other

mountain tops show just how high we are. The pass is several hundred metres to the north beyond a narrow bumpy mountain ridge. I lead us back down the other side, expecting we will find a way to the trail. We follow a dry river. I sit crouched, sliding down, one foot under my butt, the other leg sticking out in front to break and balance. Nobu sticks to the green edges of the ravine, marching steadily down the slope. The ravine soon fills with stinging nettles, fallen trees, sticky weeds, boulders. Steady progress is an impossibility. My body is tired and aching, my water bottle is empty. I curse the bloody mountain, bring it on! I yell. Kicking stones, thrashing brambles, throwing sticks out of the way, I slowly plod on, skidding, cutting myself, wondering where in heck is the path. I watch Nobu out of the corner of my eye slide 10m into the ravine, a streak of blood runs down his leg covered in dirt. Down, down, down, a creek starts to form under the mess of fallen trees and weeds, a lone cow grazes on a bluff. We reach a river, mistaking it for the one

Kalasha girls dancing

Kalasha girls dancing

summer festival dedicated to cheese and matchmaking (unofficial explanation)where we'd intended to camp. It is four thirty. We have been hiking straight for over eight hours. We shake hands knowing we ccould not have done it with out the encouragement of the other. I fill my bottle from a fast flowing stream and glug a third of it. The valley, a deep V, is already falling into the late day's shadows. I perch on a smooth boulder, stretch, scratch, inspect my cuts and bruises, then roll a charas. I munch on the pistachios and cashews and biscuits I've brought along. Nobu, eyeing the blue in the sky grow indigo, prepares a small fire. We toast chapatti and Nobu boils a pot of water, throwing in a sliced onion, tomato and cucumber. We make sandwiches. Delicious.

Morning, the shadows cling tenaciously to the dewey slopes. I hang my camping gear up the bank to catch some sunlight. My joints are sore. I haven't taken a hot shower in weeks. We eat the same food for breakfast. I find a walking stick to help me. My knee is bothering me this morning. We follow the creek down, criss-crossing amid the dry bits. More cows graze on the bluffs. After

a half hour we find the Acholgaha River, bluish brown, sprinting across piled stone hurdles. Donson Pass trail, hidden somewhere unseen along the river, shall remain a mystery. A grey haired little man approaches us from upstream, lugging a cloth sack over one shoulder. He gestures us to cross. Where the creek joins the river, the cliff face rears up. The river takes a sharp turn and on the far bank I see the well trodden trail. We remove our boots and cross the chilling current. The man in the wool cap walks with us. I lead us along the path, sheets of fallen rock underfoot. The trail climbs above the bank far above the river canyon. Men pass in the opposite direction, lugging burlap sacks, "Salaam Aleikum".

We reach the Rumbur River where Nobu and I continue upstream and our friend in the wool cap downstream. Children dare each other to call to the foreigners, holding out bunches of juicy grapes, then dashing inside walled yards. We follow the jeep track up the valley, passing a few picturesque villages, stone huts with tin roofs nestled amid corn fields on the far bank reached by suspension bridges. On the

river bank women scrub clothes, the busts of men floating miraculously, follow paths hidden in the corn fields. A pick-up truck passes, stops, offers a free lift the last mile or so. We let out at the first guesthouse. I climb up the stairs and am greeted by a smiling Kalasha woman. She shows me a room, very clean and the kitchen adn dining area on a veranda looking over the valley. 300RPs including dinner and breakfast. A good deal I decide but too steep for Nobu who parts ways and heads into the village at the bend in the road. I shower under a strong spray and enjoy a delicious lunch, chapatti, omelette, pickled veg, a dish of sliced cucumber and a heap of flakey goat cheese. I talk with the woman's daughter, Shaziya, seventeen years old. Following an afternoon nap, I lounge on the verandah, soaking in the view, recording it in my sketchbook. Nobbu returns to say he is staying in a guesthouse in the village. It's nice to have this view all to myself. Then just before sunset, a jeep pulls up with two more foreigners. I talk with them around the dinner table. Both mid

to late thirties, Sean is from NZ, having quit his job he is traveling for a year, and Iain from Utrecht is a volunteer worker in Kolkutta. he doesn't like to read. He prefers to sit and watch the story unfolding around him. Kolkutta must be a fascinating place, or Iain a rather boring fellow. Inginir Khan, the owner, joins us at the table and asks would we care to try the local wine. He brews his own. The bottle smells like paint thinner. Sean and I have a good laugh trying to swallow the wine with a straight face. Inginir asks how it is. Alright, I say. I hate to lie and say anything more. We finish the bottle slowly. I roll a charas to finish the evening. Poor judgment. In my room, before I can shut my eyes, I bring back up all the wine, all the curry, all the veg and cheese I'd eaten for dinner and for lunch.

Next morning, in the garden below the verandah, minutes before the sun pours into the valley, I am practicing my tai chi. Four hens and two cocks scurry into the yard searching for worms. A calf moans,

tethered to a post in the corner. The other boys wake late. Brunch looks like the other two meals, thick bread, rice, cheese, ocra. 'You are what you eat'. Do all Pakistanis eat such a limited diet? Mangoes don't make it over the pass into NWFP, nor bananas. In the village shops there are biscuits, nuts, dry fruit, apples, grapes sometimes. Each and everyday the guesthouses offer dhal or beans or rice or both. I have a wander up Rumbur valley in the midday sunshine. Hundreds of shades of red and brown tinted with grey and yellow cling to the undulating ridges and landslide plumes. Below the track, I cross the river to a row of farmhouses and a meandering water channel that leads me to an open-air temple ground. Amid a forest of withered old trees planted in a patch of munched grass the perfection of a golf green, I discover a wood bench with geometric carvings, backed by four totems. Upriver young men spring from boulder to boulder, long staffs in hand, prying the jammed logs and sending them down current a short ways before they jam in the next boulders. It looks like hard satisfying work, seeing

lunch, guesthouse, Rumbur

lunch, guesthouse, Rumbur

the monotony ceases with a spellbinding plate of goat cheesethe immediate progress of one's efforts. And they make it look easy, balanced and agile, like dancers. Further along, a footbridge leads into a narrow ravine. I follow the shaded river up to a bank. Further along lie a couple Nuristani villages but I am too tired in the heat to continue. I return to Balanguru and buy a pepsi in the general store. Nobu passes and sits down next to me. He likes the village, he says. He intends to stay a while in Kalasha. I return to the guesthouse and put watercolour to my sketch. The children pause from their games and watch. There are no sundays or mondays or tuesdays as such and there are no dates. It is mid summer. I have been in Pakistan over three weeks. that is how time is measured. The big festival in the Kalasha valley will end with a feast next week, a celebration involving cheese and dancing. A strange tourist draw.

Luckily, the Kalash haven't let tourism divert them from their traditions too much. In the Bumbaret valley, however, many of the guesthouses are run by Punjabi and Peshawari. A battered old Datsun pulls up late morning and

Butcher, roadside stop enroute to Mastuj

Butcher, roadside stop enroute to Mastuj

it is a common site to see meat hanging by the roadside, the butcher swatting the flies (when customers near)I hop in. I watch the valley through the dirty windows one last time. I've not purchased any handicrafts. How will I remember and cherish these people? It takes until mid afternoon to reach Chitral. I watch the sun slip behind the mountains, little puffs of cloud turn yellow and pink around the edges. I follow the recommendation of the advocates from Gudjarat and take the road past the old fort to the Pamir Riverside Inn for a fine dinner. I am early and order a pot of tea, sitting by the river, enjoying the calm. The first stars appear. The sky swallows the end of another days. The river's swoosh, the grind of gears of trucks on the far bank moving behind headlight beams. the city falls into darkness with another timed power cut, load sharing, they call it. Dinner is grossly overpriced. A family dines behind a black curtain. hotel employees saeted next to me are served first. A bowl of bland chinese soup is put before me. I feel conspicuous dining alone. It's the first time on this trip. Four fans whirl overhead at amazing speed. My gaze searches for something to focus on between dishes. something

to occupy me, flashing from one framed photograph to another like a fly. Two stuffed mountain goat busts hang over the doors. Several Pakistan posters adorn the walls with pictures of mountainscapes and trekking expeditions. A tray arrives with several dishes, a heaping plate of rice, a bowl of potatoes, a bowl of beans, a plate of fresh tomato, cucumber and onion slices and a bowl of juicy chicken. he power returns, replacing the standby generator. the fans pick up speed, spinning as though possessed by demons. Last, a dish of melon slices is placed on the table. I eat a few out of duty but feel anxious to leave. I take a closer look at the photos on the wall, the Nawab of Chitral, says one. the same man in shades in another. the Nawab exiting a plane. the Nawab with a large group of fine dressed British. The ladies' fashions remind me of my grandmother just after the war.

Mastuj I join the conversation circle on the roof at Al-Farooq's. I recognize an American couple from Rumbur Valley and am introduced to a young Swiss woman and several men from Chitral and Peshawar. The old man

on the other side of the circle calls me over. His friend wants to read my palm. The other foreigners have already been scrutinized. "You will have a long life," the first man translates for his friend. "You were very sick as a child. but god protected you. you will have lots of sex on your trip." What! I'm wide-eyed. I've misheard that I will have lots of success on my trip. After the American couple retire for the night, I sit next to Christine, the Swiss. She is traveling alone and tells me how locals react to her. We talk in French. She flew to Delhi a few months back and will loop around, heading to China then back down through S.E. Asia, returning home in time for Xmas. She seems an open-minded non-judgemental type, a seasoned traveler, guaging whether to acept a kind stranger's invitation to tea or supper. We are both headed to Mastuj the next morning and make plans to meet up.Before crossing town to the bus depot, I mail a letter and buy some grapes and chappatti and nuts. I head to the wrong depot and rush back across town my rucksack weighing heavily on

me. At the main chowk in the middle of town, I see a jeep, and next to the driver, Christine pointing through the windshield at me. I climb in. We both apologize.

The road out of town is smooth following the Chitral River north, crossing to the other bank. Each bend in the road reveals a stunning scene of raw red and brown towering rock faces, fallen boulders and the frothing silty river inspiring green stretches of bank, where small plots of vegetables and flat roofed stone huts cling. Christine and i, rubber necked, are busy taking snapshots. he barren red slopes seem to burst from the earth anxious to overtake it. he jeep follows the Mastuj River upstream past small villages, school children, girls in royal blue with white shawls, boys in baseball caps. Beyond the village of Buni the river spreads in an alluvial plain, stone islands and poplar trees. he views are even more breathtaking. he road is slow going with steep switchbacks, creeping around fallen boulders and clinging to the cliff side, carved out in a half tunnel for the road to pass. Christine and I let out at the top of a long gravel

hill by a sign that reads, tourist guest house. I don't feel like a tourist. Having survived dhiarrea, heat exhaustion and these roads, I am a traveler, thank-you very much.

The handsome young owner of the guesthouse greets us by the gate. His name is Shafiq. We are shown to our rooms. There are only four tucked behind a verandah, all looking onto a walled garden of weeds and four apple trees heavy with fruit. Thud they fall onto the wet lawn, or bang onto the tin roof. We sit with Shafiq and eat apples. Christine puts a novella on the table and turns to me, confessing she has been 'go, go, go her whole trip through India and now Pakistan. She keeps promising herself to just sit still somewhere and read a book. A vacation in the developing world often requires a vacation. Shafiq leads Christsione out the gate and down the gravel track to the bazaar. I will catch up later. Bazaar. The word conjures images of Istanbul or Cairo, countless shops, maze-like, overflowing with brassware, copperware, ceramics, spices, carpets, textiles, all displayed in centuries old archways. When I reach the bottom of the road, coursing with

the overflow of the mid-afternoon river, I discover the bazaar of Mastuj is no more than a dozen shops tucked behind grey garage doors. The most enticing store front is a bakery with glass windows diplaying coloured biscuits and sticky gulab jamun. There are no produce stalls and the general store has very little food other than biscuits and dried fruit. I cut through the bazaar and find myself atop a hillock over looking the mouth of the Yarkhun Valley. The reds and yellows and greys of the mountain sides frame the lush green riverside scattered with beige homes built of dry mud. The Yarkhund stretches all the way to the Wakhan Corridor of Afghanistan and offers some of Pakistan's most adventurous treks. Unfortunately, these are not in my budget.

A dirt path zigzags down into the valley and leads through fields of corn, wheat and grazing pastures. "Hello, how are you." calls a girl sitting with a group of freinds on the roadside. "Please come to my house." Never have I been invited by such a young person - and a girl. I follow her and two of the little boys who accompany us to the water channel

before her house. I'm lead through a forested yard of poplar trees and around the back of her house, the colour of sunburnt sand, into the main sitting room. It takes a minute to adjust to the dark. There is no electricity. It is cool. Rugs and cushions cover the floor. The twelve year old brother enters, sits next to me and jogs his memory for the few English expressions he has learned. "This is my Aunty," I bow to a young woman with fair skin and dark curly hair kneeling on the rug placing a tray with a glass of pink juice before me. I haven't even had eye contact with a Pakistani woman. I'm not sure what rules I am breaking. Aunty's name is ShaKira Shahira Ashfahan. The conversation is slow and awkward. The young boy fetches photo albums, pointing out a few with a Japanese fellow they figured I might have known. Several other photos show a TV crew in their backyard. Aunty's women's centre was filmed. I am shown to Shakira's centre, a small room with half a dozen old hand spun sewing machines standing on low wood platforms. Shelves line three walls, displaying shoes and

handbags or scrap material. On the front wall there are more photos. Aunty fetches a file and hands me several certificates, each displaying her name, "has successfully completed a three week course in..." She passes me a binder, several pages have comments from firends, perhaps from fellow travelers too. I copy the same gist of comment. Congatulations Shakira. Keep up the good work. You are doing great things for the community. When I excuse myself, the young girl hands me a bag with necklaces strung with nuts and dried fruit.

Christine is gone before I wake the next day, having caught the Natco bound for Gilgit. I practice my Tai Chi in the garden and read my novel about a thriteen year old boy in the Midlands. I'm served bread, an omelette and milk tea. Either I keep burning my tongue each day of the food no longer has any taste. Food has become a necessity rather than a delicacy to look forward to. I grab my day pack and wander into the valley under a clear hot sky. I follow a rutted road between two mudbrick walls to the old fort. I find a crumbling rectangular court. A

dirt track cuts through the tall grass, curves and passes through another gate. Adjoined to the old fort is the new fort. I spy a patch of manicured lawn. The new fort is an overpriced hotel where visiting dignitaries stay. Paths lead through the fields, past the school grounds, along water channels and skirt bramble fences and cows munching, munching. I follow along the river. Three women are doing their washing on rocks in the fast current. I lose my way in the bramble ridden fields and paths, and broken paths that become brambles and fields that become walls. The women, returning from the river, see me pacing among the bushes, trying to find my way out, like a lost calf. One carefully pulls apart the brambles atop the wall. I leap over, thankful, humiliated, dumbfounded at their kindness. I head to the bazaar and buy myself 20rps of gulab jamun and take them to the hillock. I find my perch, the same as yesterday, and sit painting for a couple hours the broad valley opened out before me. A couple boys join me. One has a slingshot he tries to stone the birds with. They yell to a man

in his yard below, perhaps their father or an uncle. "The foreigner is drawing a picture!" perhaps. I like watching the shades of the hillsides change with the sun's angle. I like to mix the paints and find the right colours. The boys have multiplied. They teach the youngest to pester me, "give me rupees." After fifteen minutes I lose my patience, "F%$# off!" They repeat it several times. "What does f%$# off mean," the eldest one asks. "Go away," i tell him. "Ahhh, in Canada they say f$#% off." The hillock is at the foot of a field palnted with breezy trees and dry furrows of earth. There is a footpath connecting the upper village and bazaar to the homesteads in the valley below. People come and go, some stopping to see what is the foreigner doing. Evening. Rice, dhal and chapatti, and some chicken. I eat with a few young men I assume are part time hands at the hotel although they have rooms here. Abu Bakr, the former owner and trekking guru mentioned in my guide book, appears when the plates are cleared. I ask him about Chamargah Pass. "Yeah, all you need is a porter." I'd

figured as much but Shafiq, no doubt trying to earn a buck, had gone on and on about his guide credentials and that the pass would require such a guide as he. I didn't bother to inquire in the bazaar if there were any porters interested in going. I will save the trekking until I reach the Northern Areas.

Advertisement

Tot: 0.108s; Tpl: 0.033s; cc: 14; qc: 23; dbt: 0.0365s; 1; m:domysql w:travelblog (10.17.0.13); sld: 1;

; mem: 1.3mb

scott

non-member comment

good entry

nice entry kevin, i enjoyed reading this one a lot. it sounds like despite running into the odd foreigner, you are really in an area very remote and somewhat cut off from the rest of the world...but i'm sure that is exactly where you want to be. How much longer do you figure you travels/money will last before you head back to Canada? take care!