Advertisement

Published: September 13th 2008

sunrise overlooking Gunung Bromo and Semeru

sunrise overlooking Gunung Bromo and Semeru

from Panang Panjang, one can in fact behold four volcanoes, Bromo and Semeru are the ones smokingHeroes: Tragic and Comic

This could be Rotterdam or anywhere, chilling in a shopping mall coffee shop half the temperature that bathes the city outside its sliding glass doors guarded by a pair of goons in blue and white pressed uniforms, until you take a closer look. The products and prices are western, made in China, Korea, Japan, western as it’s come to be known, lipsticks, yoga mats, silk blouses, skin creams, cappucinnos, handbags, donuts. The shoppers are Chinese, an affluent minority constituting roughly a fifth of Surabaya, the highest density of Chinese in the country. Many of them live in concrete mansions towering above the floodline, drive luxury sedans and tinted SUVs, employ a half dozen housekeepers, a cook, a driver, a gardener, wander the air-conditioned mall in their best clothes, eat western food and gain a few kilos, join the gym next to KFC and Pizza HUT to work off the ponch and feel a part of something modern and liberating. The mall employs the darker skinned Indonesians, the natives, pays them a hundred or so each month, they who have no work ethic, no ties to the outside world, no big ambitions, and rightly so believe that

most Chinese are corrupt and making their millions illegally. It’s clear to the expat that nobody’s paying taxes. The few sidewalks crumble and sag under construction and tropical landscaping like an end-of-the-world-movie’s closing shot, public transit employs a few rundown carbon monoxide belching busses and opelet without any proper stands or route information. Two hundred square kilometres of roadways, biways, chic neighbourhoods and squallid ghettos inhabited by some five million residents, hundreds of domed mosques calling to prayer five times each day and countless cemeteries blooming helplessly with white frangipani, block after block curbside warungs fry, toast or grill one of a dozen simple dishes. I’ve yet to discover any public spaces besides newly constructed malls or a few ‘parks’, crowded amusement zones where youths and families gather to sip iced tea. I turned down several job offers in Jakarta heeding the many complaints I’d heard or read of monstrous traffic jams and infectious pollution but after skimming a few editions of the Jakarta Post I realize I’ve also missed a half dozen interesting cultural activities that pop up every weekend in the capital. Surabaya’s single source of entertainment is in its malls where come the weekend, teenagers, young couples

Majapahit Hindu temple, Trowulan

Majapahit Hindu temple, Trowulan

capital of a once vast Hindu empire, ca. 1000-1400C.A. and families assemble for live music or a movie.

Annelies, a student of Chinese medicine in Kunming, brought out her ageing deck of tarot cards during a picnic at the lake and like a gypsy spread them on the blanket before Jacob. The rest of us watched curiously and one by one skeptics and non-believers took our turn. “Ask the cards a question,” she instructed. “Will I be happy wherever I settle in Indonesia?” She pulled cards off the deck and placed them in a jumbled pattern. “You will continue to ask yourself whether you made the right choice, whether you are achieving your goals.”

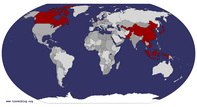

I posted my C.V. online, attached a photo and copy of my degrees, specified which countries I wished to apply for and within days my inbox filled with offers from acros South East Asia and the Middle East, each requested further documents and application forms to be filled in, followed by telephone interviews. I focused my sights on a yet unexplored part of Asia, a vast archipeligo, eighteen thousand islands stertching across the equator like stepping stones in a pond, the fourth most populous nation in the world, the most populous Muslim nation

and home to a nearly endless diversity of cultural groups, set against an alluring backdrop of fantasic flora and fauna.

Why do you want to live and work in Indonesia? I’m drawn by the opportunity to experience and learn first hand of a little known corner of the globe, to climb its famed volcanoes, dive among its coral reefs, tour its ancient temples, communicate in a new language and treat my palette to new dishes, to challenge myself, to appreciate a lifestyle at earnings one quarter an equivalent job back home, to meet and befriend a new community. After several interviews I weigh my options carefully, check blogs, email expats, research several institutions with varied packages and reputations in a dozen cities across a half dozen islands with contrasting cultures, climates and geography.

Why do I want to live and work in Indonesia? You don’t particularly like the job. You’re paid a first year teacher’s salary because the company doesn’t recognise any teaching experience apart from the company’s many franchises. It doesn’t matter that your experience was with a large, well-known, reputable and highly successful competitor. The staff room is bright white and cooler than springtime

Lambang & his buddies

Lambang & his buddies

in the refreshing hills around Malang and Batu where the volcanic soil produces a plethora of fruits and vegin Canada. The computer screen flickers at an ill and harmful frequency so the company head can save a few bucks. The walls, lined with shelves crammed with teaching materials remain strapped for games and toys. Your collegues sit at small desks facing the walls, facing away from one another. The women speak softly to each other and laugh, including a fellow Canadian, born in Trinidad, married to a local and eight months preganant with child. A third Canadian fills the staff room with his constant and enpassioned diatribe aimed at the company. The following week his mood swings and he sings elatedly with talk of his new job. We’ll come back to his story in a moment. The contract to which you agreed contained a good deal of responsibility and the majority of your students were to be adults. Instead you spend the day prepping games and teaching spoiled primary students. Of roughly eighty pupils under your instruction, five could be considered adults. After fifteen years teaching children and youth you’ve no longer the patience and it’s starting to show. When attempts to allign their poor manners prove unsuccessful, you respond with snide remarks and threats. Once a week

Nasi Pecel Madiun

Nasi Pecel Madiun

the town of Madiun serves up the best Pecel in Java, made of various greens like string beans and alfalfa sprouts and a crisp cabbage like lettuce topped with a spicy peanut sauce, the power cuts in the office, the sudden absense of a/c leaves everyone wilted and whinging more than usual. The receptionists, friendly, pretty, and punctual, nod their heads with approval and understanding but never seems to execute your needs or wishes. The ‘Boss’ comes in for a few hours on Friday to help the Director arrange the last minute schedule but is otherwise absent and unhelpful, employed with a branch in another city over an hour away. The newly promoted director never seems to hear one’s question correctly and immediately spins off on a tangent offering ideas and solutions to some echo that must be trapped inside his brain, perhaps he sits too close to the a/c. The man is nice but indecisive and surely the wrong candidate for the position. The senior teacher is a wonderful source of advice and his British sarcasm helps take the piss out of the working conditions and each day’s new confounded sources of stress. However, he cusses every other word and this feels somewhat disconcerting, like you’ve arrived up the Congo just before Kurtz loses his mind, an omen.

Cliff means well, deep down, but he is annoying, everyone thinks so. He

pushes himself onto people and situations, begins with the same self-important sermon, how he was the best English teacher in China, in charge of this and that, enjoying the best of Shenzhen’s real estate, having whichever woman he pleased, frequent holidays hither and thither. An international school in a posh district south of town has offered him more than twice what the company is paying him. He invites you over for beers and you discuss the possibility of transfering his house into your name. You’d like to have your own home in a quiet old kampung only a minute’s walk from work. He is starved for company. His quick tour of the home begins through the garage, past a hundred empty beer bottles, through the kitchen with a newly installed sink, through the livingroom where his young wife, Fiona, lounges on a rug in front of the TV, her baby asleep in her lap. On the front porch Cliff and you guzzle beers, swat mosquitos with an electrically charged tennis raquette and listen to the neighbourhood grow quiet. Learning that he once lived in the same town where you grew up, he declares the two of you ‘brothers’, an Indonesian

tendency. He relates the events leading to his move to Surabaya.

Fiona was once a nanny in HongKong before falling from grace and turning tricks in Shenzhen. She was raped by her Nigerian boyfriend/pimp around the time she befriended Cliff and convinced him it was his child growing inside her. They moved to Surabaya where they married before her family in her hometown of Kediri. The baby’s skin is black and she has an afro. Cliff realizes it’s not his but he loves it all the same and feels he is doing Fiona and the child a good service. He’s drunk and it’s late. He talks about his brother who’s undergone a sex change and lives in Saskatoon of all places. You learn of Cliff’s illegal con-artist dealings across Canada and the U.S., imagining Nicholas Cage in Matchstick Men. And he tells of the tight knit neighbourhood and the rumours here in the kampung , how he and his wife were dragged through the dirt when the small-minded community head was not directly shown their marriage license. Cliff had returned it to the government office to have the names printed correctly; such a thing would matter if they ever

chose to move to Canada. The housewives with nothing better to do spread the manure and hissed whenever she passed, ‘slut’, they would call.

A week later life has thrown him another curve ball. Once Cliff had cut ties with the company, the contract for the private school metamorphosed into a hellish deal, at half the salary, he’d even have to pay to have his family live with him. The week before he exaggerated his close ties with the Chinese community, his understanding of their business approach and education style. Tonight he curses their conceited and arocratic disdain for the native population, namely his wife and her child. It’s late once again and he’s drunk. It’s just between you and he, he says, but he’d like out. He’d like to return to China, or to Canada. You’d heard from other employees that Cliff already tried sneaking out of the country with the baby. Cliff and Fiona fight in front of you and another guest. Unmistakenly, in her funny accent, Fiona has many colourful names for her husband and expresses her anxiety that he wishes to return to Shenzhen to see his ex-girlfriends. You bump into him a few weeks

the preacher

the preacher

he looks cute but he droaned on foreverlater at the check-out stand and feign illness, you are quiet and absent, almost holding your breath, not wishing to out and say it, that he is perhaps the most stressful individual you’ve encountered in a long long while and were you to be stranded together on a deserted island you’d find a million other ways to entertain yourself rather than share his company. You never know what to believe of his. He’d assured you the house was 99% yours, he’d call in a day or two, but his call never came. He’d even told his neighbours that you’d probably be moving in, and that you were gay. “Uuuh, why did you share my sexuality with people who’re complete strangers to me and need not know?” you ask him. Don’t worry, brother, I was pavin’ the way for ya’, he assures you. “Pavin’ the way,” you think to yourself, what the f**k planet is he from?

In fact you kind of avoid the expats. You see a few in the gym or in the mall and greet hello in passing, attend an occasional backyard barbecue or an evening out to share a drink at the bar. You learn that

Air Terjun

Air Terjun

waterfall, Batua couple staff chose the company because their criminal records and history of alcohol abuse were not a problem. The majority of the western staff are in their mid to late forties, a good number of them unattractive men who have found vivacious young women to bunk down with. Strange but you begin to see a wider picture of this cross-cultural phenomenon. The women benefit from a western man who can treat them better than a local man could emotionally and financially. It is nonetheless a jarring sight, and one that you come home to every evening. You learn to see beyond the appearance of things and appreciate that though his girlfriend’s the same age as his daughter back in Sydney, the couple is happy and mutually benefiting from the experience. They are both good and you enjoy their company. Your other housemates, a married, forty-something British-Canadian couple who arrived a month before you from Shenzhen, though cannot speak a word of Chinese after living there for three years, spend altogether too much of their free time locked into the cable TV channels, thankfully recharging on American pop culture. After three months in Surabaya, she hasn’t yet tried the local

cuisine nor has she crossed the street from her office to the city’s largest flower market. Why are they living abroad, you wonder. And why haven’t you moved out? After four years living alone and without TV, you must share a single bathroom with two grown couples and a livingroom with a sony altar to the omnipresent, omniscient American Way of (sucking the) life (out of humanity).

Cyber Romance

To avoid the expat community I make use of two on-line profiles. I meet locals, someone to show me around, or with whom to share a nice meal. On one site most of the respondants fail to read my ‘desire’ and send short messages with blurry naked pics attached, sea creatures covered in black fuzz. Forunately the other site that I’ve been using for several years typically attracts a more reputable clientel among whom I’ve even managed in the past to forge longterm friendships and relationships. In the former I display a pic of myself on holiday soaking in the buff in a hotspring, less pagan and more of a catholic reproduction with the bits and pieces cleverly hidden from view by cascading water. My ‘looking for’ paragraph reads as

a list of ‘not looking for’, a reaction to the countless desperate cyber weirdos. The latter, more successful sight, exhibits mostly headshots with varying ethnic headware; a bouffant red felt hat of the Hmong, a mountain people in northern Vietnam, a skull cap and shalwar-kameez worn among the Pashto of Peshawar, and against the heat of midday touring the old fort in Lahore, and summer hat, Osaka-retro, whilst window shopping in Amerikamura. I can take down my guard and share an honest self-synopsis. In Surabaya, however, neither site guarantees users of sound mind.

Lambang’s profile includes two pics, in both he is fully clothed, one presents a wide smile, he is rocking backwards in a bold fit of laughter, cross-legged in the other, he plays his guitar. He picks me up on his motorbike and we head to Tungunjeran Plaza, TP, in the city centre. Indonesians love to abbreviate. He drives quickly, weaves through traffic, the bike and his body are one, his passenger clamps his jaw in panic, squeezes knees against driver’s hips when passing trucks within inches of injury. There’s nowhere really to pass the time in Surabaya besides a dozen or more super malls that quarter

warung

warung

cheap local eatsthe maze of paved congestion. Curiously, many of the traditional markets, poor, simple plazas where vendors sell fruit and veg, fish or poultry or odds and ends, have gone up in late night blazes and like a phoenix from the ashes rises yet another new supermall. Locals seem to understand that the government is beorchestrating these arsons but I suppose there’s not much that can be done. Indonesia’s corrupt - surprise! Lambang leads me through the sepeda parkir berat where I watch carefully how riders pass registration slips to the guards. We climb the lift and the escalators higher and higher in an air-conditioned mecca to consumer culture. Stong odours fill the food court, a creperie wafts enough sugared air molecules to pain my teeth, dishes cooked in MSG glow and emit flavourful substitutes. There we chat on the edge of a typically American scene embraced by the developing world as a sense of freedom and democracy. Lambang has a nice smile and he laughs a lot. We meet again and I’m introduced to his buddies.

We meet early one Saturday morning, my first adventure out of town, to refresh amid waterfalls and hotsprings in the cool countryside near

Pasar Atoum

Pasar Atoum

shopping mall frozen in the early 80s, two hours weaving at break neck speed through traffic, inhaling carbondioxide, and the sulfuric sting of an overflown mudpit in Porong district just south of Sidoarjo. A giant wall has been erected to contain the mess but traffic slows, even the traintracks lie coated in fresh muck, over two years since May 29, 2006, “when hot stinking mud first started spewing from a hole in the ground.” I learn in an English edition Indonesian magazine, Tempo, how eight villages lie submerged along with hundreds of hectares of rice paddies and several factories. Inhabitants have lost their community and livelihood, have received insufficient government aid and have relocated elsewhere in the region. To the west the soft blue silhouette of Gunung Penanggunan rears over the traffic and roadside factories, followed by two more volcanoes, Gunung Welirang and Gunung Arjuna each looming over three thousand metres high seperated by only a few kilometres of protected reserve. Lambang, his buddies and I follow a road climbing into the hills behind Malang to the village of Batu. At the end of a long forest drive we reach a carpark filling with Pariwisati coaches, and other daytrippers. Beyond the row of shops and canteens,

Pasar

Pasar

in China townlandscaped paths lead beyond a musholla where Muslims are washing and tending to routine prayers to a pool of cold water filling with a strong broad jet from a twenty metre high waterfall and cascading into a narrow stream. The scene is crowded with families escaping the heat and haze of Surabaya. Our train of motorbikes continues to other lush Air Terjun and Air Panas hidden among the valleys of the half dozen slumbering volcanoes. The roads snake along hilltop ridges and offer stunning views of the rolling green farmlands dotted with dense little villages. For the first time in several weeks I feel a shiver as we zip beneath an overcast sky through the vegetable patches of Tretes and Trawas.

Lambang introduces me to the local cuisine. After work he leads me to his favourite warungs, roadside food stalls cooking up barbecued chicken, fried fish, meatball soup, rice, noodles, duck, beef stew, eel, catfish, curry, jackfruit, most served with a hot chilli sauce, sambal, requiring a cool glass of Es Teh. Several others remain a mystery. We sit at low plastic stools, the traffic whirs past, locals banter, a young child plays with an older sibling, young men

sambal

sambal

spicy chillissmoke strong cigarettes, black flies tickle my leg hairs. Bar hopping or clubbing no longer holds our interest. Instead lying in bed under the fan we chat and form a bond, for once a friendship between two young gay men. Lambang is Muslim, knows most of the Koran by heart, and I find his thought, speech and actions in tune with my Buddhist approach. One evening reading from a Penguin Classics English translation of the Koran, the chapter titles in Arabic, Al-Fatihah, Al-Ra’d, Al-Rahman, Al-Nasr, Lambang asks me what is the last chapter in the Koran. Before I can answer, he replies, Al-cohol, a joke from his high school days. He tells me how the neighbourhood looked back in his childhood, how fields of wild grass grew where the Chinese mansions now stand.

A Javanese Wedding: Dine & Dash Customs of Indonesia

I am invited to his cousin’s wedding in

Madiun, Lambang’s hometown, a few hours west undertaken on a last minute bus, seats already filled. The sunlight dims, headlights glare, an evening breeze sweeps a stench of manure over the farmlands, stirring a sudden homesickness. A painted sign on the shop window advertises Pecel Madiun. The fluorescent glare

adds a laboratory aspect to our late evening meal. Lambang’s cousins fetch us from the warung, wisking us off the highway into a farmroad’s refreshing darkness, shadows of a sugarcane ocean sway either side of the road, the nightsky stretches overhead filled with distant worlds. Weddings occur each weekend in nearly every village and neighbourhood of Indonesia. Large tents are erected usually across a main road or along a highway’s shoulder, usually diverting traffic, or creating of the traffic a new traditional instrument. Massive speakers are installed, waves of dantung music crash across roofs and reach down the back roads til the wee hrs of the morning.

The womenfolk arrive dressed in light blues and yellows and pinks, coral made of silk, each covered modestly in jilbab with children in tow, scrubbed vigourously and forced into their finest. Fathers, husbands, sons and brothers sit apart from the womenfolk, a collage of psychadelic batik in swirling seashell browns and dark blues. Beneath the tent a simple stage stands at centre where the bride, bridesmaids and her parents gather, and pose stiffly before a gilded ornate backdrop. The bride is caked in make-up, wrapped in heavy dresses and her hair done

up like an alien vixen to temp Captain Kirk in an early Star Trek episode. Among the rows of friends and relatives, children scamper, eat through their gift boxes of sweet breads and salted crackers, the men as always smoke their billowing kretaks, mothers admonish their children or bounce babies in their lap. From down the lane approaches the groom dressed in a similar fine black with gold lace, a large knife tucked in his belt, followed by his groom’s men holding aloft golden parasoles, leading a long train of guests from the groom’s side of the family. The wedding party stands rigid before the Imam, a single fan whimpers next to the husband and wife to be. The bride’s mother, a short unattractive woman, wears a stern impenetrable expression, and stands like a rock behind her daughter with her hand held against the small of her daughter’s back. Hard to say whether she is supporting her child or herself. The guests settle into their chairs in a trance catching a word or two of the Imam’s prolonged speech. Lambang’s and my seat on the edge of the tent’s protective shade affords a peak of the back courtyard where several

women finish the last touches on the banquet. My friend and I are the last to file past the wedding party, shaking hands with the parents. The groom’s father speaks to me sharing how he is honoured by my visit. I bow humbly, clumslily and respond that his son’s wedding is the first I’ve seen of it’s kind. Immediately I feel awkward with my anthropologist’s remarks and scurry into the queue for the reception. Guests mill about in the shade of low leafy trees chatting, eating bowls of nasi pecel, fried rice, gado-gado, some already preying upon desert table delicacies.

The village isn’t much, a few crisscrossing lanes bathe lazily under an exhausting sun, a familiar sketch of half dressed children, noisy fowl, and farmers tending quietly to their patch of earth. In the morning leading upto the wedding Lambang leads me to the ravine where he once played as a young boy. Dark red dragonflies flitter among the mossy stones. A woman crosses the water to a smooth rock where she sets about scrubbing the laundry. In a warung kopi sits Lambang’s Uncle and a few other men their feet up on the benches perched Javanese style, like

frogs. The tips of their cigarettes are covered in coffee urns. My gaze flitters about the shop eyeing the motionless hands of a clock, a calendar with a photograph of a mosque in Sumatra and two representatives of a local political party. The woman behind the counter either does not notice or pretends not to notice the open fly of one of the young men’s shorts, the head of his penis poking through. Alerted by his friend he looks down, laughs and quickly arranges himself.

The guests to the wedding have travelled a considerable distance on less than friendly roads to which they return directly following the reception banquet. In Indonesian style guests stay only long enough to eat and allow the food to digest during their return journey home. Lambang and I secure a bench on the bus and nod off. He tells me a few days later that the man seated to his other side tried carressing Lambang’s leg, and asked for his number, and that it wasn’t the first time such a thing had happened to him.

Indonesia's Most Popular Sunrise

For a while Lambang has been waiting to hear back from several job applications,

dancers from Ponorogo

dancers from Ponorogo

a free 'cultural evening' to celebrate Surabaya's 615th b-day, included musicians and dancers from Korea, Thailand, Brazil and a troupe from the village of Ponorogo, in E. Java, famed for its elaborate costumesaccounting and computer programming positions in cities across the archipeligo. Losing patience he moves to Bali and accepts part-time work at a cousin’s mobile phone shop. He texts me a few weeks later with strange news, he is living with an older Dutchman who has been operating several villas in Ubud and on the north coast for over a decade. Lambang had been in touch with him online for some time but never really planned to meet the guy. My friend is helping him design a villa’s interior as well as a little café in Ubud. I text him back, a little dumbfounded, write that I am happy for him. He has a free place to stay, frequent use of the man’s motorbike and they often share the weekends together exploring the island. One Friday afternoon Lambang texts me, he is back in town for a few days, am I free. We share dinner and I propose a trip next day to

Mount Bromo. We leave the city Saturday mid-afternoon, the traffic squeezes slowly through the old section of highway in Sidoarjo and slows again on the rough section bordering the mudflow. The road forks, south to Malang, east to

Probolingo and onwards to Bali, a new stretch of road with less traffic. I’m still not used to Lambang’s death defying driving techniques, mainting a steady 80kmh through congested traffic, passing up the shoulder or daring oncoming traffic. I feel like the stunt girls in one of Terrentino’s latest co-productions, Slaughter House Five.

Not long before sunset we reach the mountain’s approach road, Lambang points south to where a mountain stretches several miles across in a faint indigo tapering towards a thin band of grey brown cloud. Forty kilometers to go, up, up, up, into the crisp evening air, gearing down, engine revs, Lambang assaults the hairpin switchbacks, I imagine ourselves flung off the road into the side of a house. Sunsets sink quickly near the equator, the stars appear on a black canopy slightly greyer than the mountain peak jutting ahead of us. Our bodies are shivering when we reach Cekoro Lawang, a village perched on the caldera. Across from a sundry shop sits a young local man wrapped in a blanket from whom Lambang inquires about accomodation. We’re recommended a cheap inn a block up and to the left. We take a windowless room in the basement

and after supper in a cramped and cozy warung manage five or so hours of sleep. Lambang’s mobile alarm wakes us at two a.m. We splash ourselves in the near freezing mandi and dress. Outside a heavy mist shrouds the road and the figures of young men who’ve since arrived mill about the carpark chattering with friends, as excited as highschool boys. The nextdoor warung is crowded where several more tourists huddle around a small charcoal fire, eyeing Lambang’s short pants and sandals. They are all dressed in layers. I too am wearing longjohns. They are even more surprised to learn that we will hike to the peak. Lambang asked me if I wanted to hop a ride in a jeep, about 8$ each for the return ride, but I thought it rediculous to climb a perfectly hikable mountain peak in a 4x4.

We decline the shadowy figure hawking wool caps and creep unnoticed past the tollbooth, venture towards the edge of the village to a path teetering along the caldera stretching into the vaccuous night. A cold wind scrapes my face like rough gravel on a schoolboy’s tumble. We’ve each a small torch, a dull glow to illuminate

a patch of wet earth in which to find our way. A dog barks. We lose the path and carefully tread across a vegetable field, and follow a paved road winding past small farmhouses that appear suddenly before us and disappear as quickly. As explained the road turns to gravel and narrows to a footpath along the edge of a forested incline. We spend a while here exploring the paths trying to find the approach, and backtracking down a sheer cliff face before managing to uncover a well manicured staircase hidden in low shrubs. Our pace improves. Lambang comments about the time. We have to rush. We have a view now of down the far side of the mountain to the towns and villages near the coast, a vast plain strung with traffic lights and lonely dwellings, a manmade impression of the constellations overhead.

The sound of a truck is heard approaching. A pair of parked headlights blinds us as we reach the road. In the distance a train of headlights can be seen weaving up the mountain. Soon a caravan of jeeps filled with less than adventurous tourists is passing us. Up ahead they pirhouette in four point

turns and find a niche along the soulder. I’m astonished. Climbing the road, I lose count of the jeeps at around seventy or eighty, I have to jump out the way of motorbikes accelerating through the bunching crowd of tourists swarming between two banks of shops selling coffee, instant noodles, postcards and wool hats. The majority of tourists are westerners in wool caps who were soaking on the beaches in Bali twelve hours earlier. The viewing platform is a sea of shivering shoulders and necks craned eastward searching for the first rays of sunlight. Hundreds of digital screens aim towards the approaching sunrise and to the puffing summit of Mount Semeru, a long day’s hike to the south, slowly coming into view. The crowds jostle for just the right shot. A loud Oooooooh erupts among the spectators as the golden orb raises itself above the distant horizon, beautiful how something so predictable can appear utterly amazing.

Like a movie going audience most of whom jump from their seats when the credits first appear, soon half the gathering slinks off back to the jeeps destined for the next scenic point of interest on a whirlwind tour of Indonesia. Lambang leads

me across the viewing paltform. I wait behind a wall of photographers, their large weapons pointed towards Semeru. A gap opens, I climb the railing to behold perhaps the most imposing view of nature I’ve witnessed in close to a decade not since the Nile spread before me stretching away from Luxor hemmed in by two narrow bands of lush green in sharp contrast to an endless and daunting desert, quantifying the moment in hindsight if only to benefit the reader’s comprehension, without intending to belittle the splendour and prehistoric awe of the landscape. A broad sea of rolling cloud lies across the plain of a once massive crater from which has sprouted over the passing ages like bubbles popping on the water’s surface, the once perfect cone of Mount Bromo has since crumbled to half its height and emits a steady stream of hot vapour and gas blown upwind like the entrails of a steamtrain’s exhaust. From atop Panang Prajang’s viewpoint the cone of Mount Batok stands dormant directly in front of the more distant Mount Semeru, the latter puffs like a tobacco pipe. The earth is an eery red, the very color of the early sun, the dark

of night lingers in the forest shadows, and an ever-brightening blue fills the firmament. We descend back down the trail, a young Belgian couple follow after, and ask Lambang for directions across the plain to Bromo. My friend and I walk slowly enjoying the views. The sun’s rays climb the caldera’s edge. The sea of cloud evaporates revealing a road across the sand to a carpark and a temple at Bromo’s base, less than spectacular this trail of army ant tourism.

Christians, Muslims, Hindus, Buddhists

There follows Lambang a string of blind dates with young gentlemen of Surabaya, varying levels of English skills, varying degrees of confidence, or rather some act less awkward than others, each is closeted and all are boring, the result of being brought up in this wasteland, the six hundred and fifteen year old evolution of Surabaya. The men in their mid twenties live at home with their parents, are either Chinese and attend church every Sunday or are Indonesian, studied the Koran from age 6 to 14 and make no excuses now for not praying five times a day. I meet them in noisy shopping mall food courts where their dormant English resurfaces in

a quiet struggle, their shy eyes avert mine. Nick’s on-line profile is all body shots and for obvious reasons, he is without a chin. He introduces me to a private sports facility tucked in a far corner of my upper class neighbourhood. Giant advertisements for protein shakes and muscle relaxants hang above a 25m pool, it’s bottom without the safety of painted lines or markers sends patrons paddling to and fro in all directions in constant near collisions. Why, I ask my friend, is there a metal bar like in a ballet studio bolted all along the pool edge. Well, so those who can’t swim have something to grab on to, he tells me. This aquatic facility would be called a pool, bereft of the term “swimming” such as soft cones lack “ice cream”. Nick recommends I don’t patron any of the pools in Surabaya. On my suggestion we tour the city’s beachside theme park,

Pantei Kenjeran, a run down series of temples and dejected food stalls frequented by young couples escaping the watchful eyes of a traditionally minded society. The quiet and open space feels nice. I soon realize Nick is looking for a discreit encounter to fill a

routine two hours each Saturday afternoon. No thank-you. The number of hits to my site decreases sharply upon clarifying that I am not seeking a f**kbuddy. At age thirty-one-and-a-half something strange is happening to me. I think about sex no more than twenty minutes a week, ten minutes of which is spent contemplating the fact that I am not thinking about sex the rest of the time.

Stefan is a taller version of Nick opportunely interested in culture. On a sunny Saturday morning we zipp off to

Trowulan, a sleepy village an hour west of the city, once the capital of the Majapahit Kingdom, “the largest Hindu empire in Indonesian Histroy” that reached its artisitic high point during the late thirteenth and fourteenth century. The reconstructed red-brick cores of a half dozen temples lie amid manicured gardens scattered among the villages and fields of sugarcane. Junior high school students take this sort of fieldtrip. I feel a little awkward intentionally setting out on this exploration and subjecting my gentleman friend to a hot morning of geriatric Indiana Jones. We wander through the museum’s collection of stone demons and deities, temple pieces and steles. On our return journey Stefan and

I stop in Mojokerto where I’d noted on the busride to Madiun that several shops line the highway selling stone statues. Too bothered to comparative shop or haggle for too long, I settle on 75$ for a 60kg statue of a seated Buddha and a five kilogram carved head of a monk, including same day delivery to my home address. In fact, I hop in the truck and direct the men back to my place while poor Stefan follows on his motorbike.

The men follow my instructions reluctantly and drag the statue to the backyard. The stone buddha is propped up and left to watch over the weeds and rubble.

Advertisement

Tot: 0.12s; Tpl: 0.021s; cc: 14; qc: 30; dbt: 0.0437s; 1; m:domysql w:travelblog (10.17.0.13); sld: 1;

; mem: 1.3mb

Treveni

non-member comment

Hi very well expressed!!! I am from malaysia, Mount Bromo looks so dam adventurous, can u pls tell me which time in the year could be the best and safest visit to this place. Take care bye.