Advertisement

Published: November 1st 2007

Welcome Back Tea

Gilgit Next day I leave town on the earliest minivan to Gilgit keeping in mind a list of places still to explore before the China tourist visa expires. I meet so many tourists on return visits to Pakistan and no wonder, I could've easily spent another day in Skardu, to explore the back roads, putter about the market, or climb up Karpochu for the splendid views of the valley and to investigate the ruins of the fort. Two young men from Peshawar employed with the Agricultural Dept. in Gilgit share the bench. One is longer legged than I and long haired like a Bollywood pop star. He speaks in Urdu splicing English expressions. His friend, sitting between us, struggles to respond in common English phrases. They laugh and keep each other entertained on an otherwise quiet ride. The wind tugs the curtain closed on my window seat. A fallen cargo truck slows our progress and later a patch of road being tarred and rolled. The young Peshawaris joke with me as to how things are done in their country. Continuing down river, the men cease their joking and discuss religion with me - at their request. They

invite me to their place of work for lunch, a pot of juicy chicken harari, rice, spinach and yogourt, where the conversation pursues the topic of Peace TV. The boss, a devout muslim following the prophet's examle with a long curly beard, explains about a muslim scholar with strong understanding of the world's major religions who lectures audiences in India and is televised on Peace TV. When I later inquire at the hostel as to this station, the manager looks at me as though to say, 'are you crazy? what could you possibly hope to learn?'

Morris, the outspoken German who has climbed nearly every glacier from Nepal to Kyrgyzstan, chatting with the kitchen boys, tells me about their twelve day trek to Hispar La and Biaffo Glaciers where one of the porters fell three metres down a crevice. They saved him but lost the pack of food. The English woman who'd worked several years in Xishuangbana and was trveling with her Chinese husband recounts her five days at Rupal. They waited five days playing every card game they could summon before the clouds cleared revealing impressive views of Nanga Parbat and Rupal peak. I meet Caroline, the much

rumored English teacher in Mastuj. She is surprised to learn I'd heard of her stay in the isolated town. She admits the experience was rather claustrophobic, especially living with the overbearing host father. She had joined Morris for the latter stin of the trek and was taking several days to recuperate. A man with a copy of

Crime & Punishment introduces himself, Carlos, from Columbia. He'd done his graduate studies in Public Admin at Carleton University in Ottawa back in the late eighties courtesy of a Canadian grant. We discuss Dovtoyesky and Gabriel Garcia Marquez. I recommend he reads DeBerniere's

Birds Without Wings whose narratives touch close to the intimacy of Marquez and he advises Tom Robbins'

Life With Woodpecker, "the man touches on all subjects. He's a genius." I hop on the internet to learn that my big sister is the proud mother of baby girl, Ayla Louise, born 17th August. In the pics she looks exhausted, her husband elated.

Exercising my tai chi on the rooftop, I spy beyond the high brick walls, locals coming and going into their morning. The cow and rooster in next yard make their presents known, "I am. I am." The tenants

in the back block finish their breakfast and commence drilling and sanding. All this before seven. A leisurely morning reading in the garden, Caroline introduces me to Martin, a protestant from Armagh, who is keen to hike in Nastor Valley. Leaving the guesthouse confines into town is a slight shock, the contrast of rose bushes and trekking gear to the armed soldiers and chaotic taxis. In the markets I fetch lunch and supplies for the next trek, vegitables, rice, tea, sugar, a bigger pot and refill my gas stove cannister. Come evening spoiling myself with a peanut butter and banana chapatti, I talk with an older fellow from Hampstead, living only a couple blocks from my brother in fact. The gentleman is three years from retirement in the IT business. Every year he leaves his wife who's content to stay at home for a few weeks of travel. He has covered most of the globe and enjoys a second home in Mauritius. I'm not even a hundred percent sure where that is. The electricity has been out all day and the mosquitos, without a fan to cut their advance, spend the night feasting on my flesh.

The Purple Haired

Porter

Naltar Valley In the morning remains of the small battle coat the walls in blood. Martin has procured a tent, and after discussing with Morris and the guesthouse management, we decide to hire a porter. Our lift, a cargo jeep, parked beyond the kebab shop, is already piled with sheet metal, a cage containing twelve frantic plucked chickens and five other passengers. Riding shotgun, a man introduces himself as our porter, and a friend of the hotel manager. He asks 3000 rupees. I tell him flat out no. He looks about fifty, his hair tinted purple with henna and snipped halfhazardly as though he'd had to remove some chewing gum. I negotiate for 2000 rupees, considering 300 per stage plus 200 rupees transport. He hums, haws and shakes my hand, repeating the aforementioned proposed fee. After another four men pile into the back, including a grey haired fellow sporting old driving goggles and lugging a crate of food, we are off. Naltar Valley is an hours drive up a side road. I crouch over the chicken cage eyeing the KKH across the river. We turn up the valley, following an incredibly rugged dirt track inches from a tumbling

river. The wooded hillsides enjoy significantly more rain than Gilgit, perhaps why the British once erected their hill station here. Presently it starts to rain. Crouched, pinched, rained on and facing backwards down a jostling dirt track and a flock of unfeathered fowl. Pakistan doesn't get much better than this.

Our porter helps us settle into the backyard of a cheap guesthouse in Upper Naltar, a white cement structure as you first enter the village. Fields with a sprinkling of humble cottages spread across the hillside, far below dances the river and across the bank lies an elegant looking guesthouse among the pine trees. I don't like the porter. I keep my opinion to myself, that his behaviour defines the very word shifty. Martin is optimistic and mentions no fault with the purple haired gentleman. Martin and I have little to discuss at dinner, two very different people. I can't understand his passivity for someone who has traveled the sub-continent on several occasions. The next morning before I can argue, he has agreed to pay the young guesthouse cook for the milk and tea and porridge which we'd packed along with us. We set off across the village. Boys

in dark trousers and brown dress shirts, polished shoes and ties and girls dressed in light blue or purple shalwar kameez head to school, passing us with cheerful greetings. At a rise in the hill the porter stops to chat with a construction crew, most of the members seated smoking in the shade. I have to wonder how much time a Pakistani spends in shaking hands and sharing small talk. The nation is sociable to an exhausting degree. A tractor comes trundling along the track and the porter takes advantage of a free ride. Martin and I decline prefering to spend a few pleasant hours crossing the farm tracts and pine forests. The sky is clear and the only noise is the swish swoosh of the river below. The hills start to close in and the road to undulate when we discover the porter reclining on a grassy bank overlooking a crystal clear pond. He is chatting to a few young men who operate a simple campsite on the banks, Naltar Lake Hotel, a slight misnomer as their is no hotel, only a tent, and the lake itself is lies a couple kilometres above the eat ridge. We join them

Ghakuch

Ghakuch

dusty, windy, noisy but in the right light...for a cup of tastey mountain tea and admire the strange colours of the algae blooming like giant toad stools below the clear surface. The porter recommends camping here the night. "All the English peoples camp here." Martin and I agree it would best to press on. Beyond the lake the path dissapears into a wide gravel bed and then another before climbing a grassy pasture dotted with primitive shepherd dwellings which appear like huge bonfire piles. A shepherd approaches us followed by his wee daughter and offers us a cup of yak milk tea. "All the English peoples drink tea here," adds the porter. Martin and I have learned to stomach the potion with a convincing smile. Only mid afternoon and wanting to contniue further, our progress is halted by the porter who argues that the next camp is too far to reach today. Amid the primitive dwellings, bleeping sheep herds and the settlement's curious children I fall into a cozy nap and wake sunburnt a couple hours later. The sun slinks behind the hilltops. The sheep and cattle descend from the upper slopes and file across the narrow bridge urged on by the shepherd's calls. Martin and I

crouch out of the wind behind a large boulder and prepare a pot of rice and vegetables. The porter checks in with us. He is staying the night at a sturdy rock dwelling down the pasture from where a billow of smoke escapes the chimney.

The walk as far as Lath, the next shepherd encampment, is pleasant but thereafter begins to climb ever steeper. The hillsides are verdant with wild flowers and honey bees. We rest at Shani to boil a pot of tea and refuel on apples. Reaching Pakora High Camp, Martin contemplates the long descent ahead and though only early afternoon considers it best to camp here. I disagree owing to the bitter cold and lack of shelter from the wind. Over the pass, Pakora Glacier spreads out before us, a sheet of ice strung from the Naltar mountains to Sentinel. In sandals, the porter bounds off across the ice. Martin, equipped with a ski pole manages to keep a pace but I fall behind cursing my sore ankles and watching closely for their footprints, fearing I discover a crevace. Beyond the glacier, Martin and the porter's silhouettes vanish over the horizon. I plod ahead over the

loose rock following a ravine formed between the ice and the red rock it has pushed up the side. Th hour and half hike proposed at Pakora turns into three. My ankles have slowed my progress considerably. I haven't seen Martin or the porter for nearly two hours. Each time the path enters a wooded glen, however sloped, I consider stopping to camp the night. I find the rest of my party standing unsettled among low tangled trees on a few feet of relatively flat ground. Instantly I remove my pack and lie down. "We're camping here then," I offer, less as a question, more of a statement. "Well, it's up to you, Kevin," quips Martin. In response I unpack my tent and lay it out beneath a scraggly tree while the porter looks on still hoping I'll rescind. No, to be fair, he stands there like a dog at a gas station in the desert waiting for the next truck to chase. I am not fond of the man and it has little to do with his purple hair. He neglected to guide today, doesn't help with the cooking, contracts himself out without the bare minimum of equipment and

stuffed chapatti

stuffed chapatti

just when I think I've had every chapatti conceivablegrumbles when I stow away the stove and pot in his bag - which he has borrowed from Martin. I sleep poorly. The leafless little trees shaking in the wind, scratching and stirring outside the tent. Waking for a piss in the wee hours of the morning, I fear there are ghosts in these isolated woods.

The porter leads us next morning down the valley to Jut, a pasture of primitive shepherd huts. We set the pot to boil and cook the last of the porridge sweetened with dried apricots. The trail descends a further three hours along a narrow donkey path high above the Pakora River. I take the lead and try to forget I ever hired the porter leaving him and Martin several turns behind. We reach Pakora, a village spread midway along the Ishkoman Valley's west bank. Crossing a wood bridge we are lead to a "guesthouse", or so says the porter. The young woman of the house arranges lunch. Her son brings a jug of water and tray piled with grapes. We nibble, peel off our socks and soak in the view, golds and greens and a ribbon of blue stretching south to Chatorkhand. Though

the road is paved and the distance only nine kilometres, the porter insists it's a five hour walk. The young woman returns with a platter of rice, a bowl of cooked spinach and potatos and a bowl of stewed aubergine and three glasses of lhassi. Delish. Martin and I rearrange the contents of our bags and pass the porter his oversized sleeping bag. "Medina," he says. It belongs to the guesthouse and he assumes we will carry it for him. I pass him the agreed fee of two thousand. "Why?" he says looking trodden and downcast. "Uuuh, because this is what we agreed." "Sorry, my English very bad." I list for him the responsibilities for which I'd thought he was hired and which he failed to accomplish. Martin hands him another 200 and we leave him for the road. A shopkeeper informs us there is no jeep hire but it's a mere thirty minutes walk to Chatorkhand. Outside town a minivan pulls up, among its passengers the ever smiling and recently paid porter.

We are in luck today. In Chatorkhand, a bazaar one dozen storefronts in length - a couple general stores, a barber, two guesthouses and an ice

Minnapin glacier

Minnapin glacier

autumn leaves foreshadow the cold nightcream vendor, we've only an hour to wait until a minivan will carry us to the highway. A cricket team slowly assembles in the village, the young men dressed in sporty polyester adidas rip offs. We all pile into the van and make for Gakuch. The paved road swoops along the fields bordered by rows of polar trees, the roadside finished in a smart landcsape of rockery and dried purple bramles. The wind blows fiercely as we cross the Gilgit, sand clouds set sail off the river banks. Despite the sand in my eyes, the black flies and the exhaust, Gakuch is picturesque when waiting for the next ride out. The shops awnings wave dull shades of red or blue. Dark silhouettes wander up and down the road under a majestic afternoon sky, the sun piercing distant clouds down valley.

The Consequences of Uncooked Mutton

Minnapin By midday Martin is Islamabad bound and I too am set to go, laundry scrubbed and dried, stomach satiated on kebeb, peanut butter and fresh fruit. One of the kitchen boys, Elias, rather handsome until today's new haircut, guides me to one of the dozen or more bus depots in town. If

he'd just said follow the stench of cat and dog doodoo I'd have found it myself. In a far back corner of the bazaar, beyond the mosques, where the neighbourhood's pets spray the pile of debris with coat after coat of piss until it burns the oflactory tubes of any tourist dim-witted enough to arrive early for a van that regularly departs nearly two hours late. But it offers me a chance to contemplate tourism in Pakistan, traveling with money or traveling with time. Of the latter I have plenty and it makes a great difference in my experience, positive and negative. At the moment I'd settle for a costlier mode of transport rather than a waiting room consisting of a log pile strewn over the cat's sandbox now hissing in the afternoon heat. No matter, for just under a dollar, I spend most of the day sitting shotgun next to the driver's midgit right hand man - seated at his left however, covering fifty kilometres of the Karakoram Highway. The van stops every five hundred metres to pick up and drop off members of the nation's most extended family. We stop half way in a shaded row of wooden

shacks overflowing with fruit, juice, chai, candies, biscuits and steaming, bubbling foods. I try a

stuffed chapatti. To think, after all the chapatti I have consumed, this is the first village ingenious enough to fold them in half and stuff them with meat. Perhaps they own the patten.

The KKH winds up the Hunza river and beyond a bend, Rakaposhi Glacier appears, its snowcapped peaks glowing french vanilla in the late day sun.The end of a dirt track, the tired engine struggling the low incline, dirty young children outside the window keeping pace, we pull into Duran Guesthouse. I wave the friendly driver and his midgit farewell. The hotel is posh, a white lodge set amid cut lawns furnished with white lawn chairs, studded with rose bushes and an apple orchard growing several varietes. And towering above, Rakaposhi. I am served a welcome tea in the garden. I admire the mountain remove her french vanilla veil, her dark undergarment humble amid the twinkling stars. The cheap rooms are behind the lodge, looking onto the orchard and within ear shot of the generator. An irregular drum beat accelerates into a steady thumping and sets the verandah's yellow bulbs aglow. At

dinner, a tray piled with basmati rice, a stuffed chapatti, a bowl of spinach, a bowl of boiled potatoes in a light tomato sauce is set before me while I chat with a Swiss couple who've driven overland in their VW. They had to pay over a grand for the permits to pass through Xinjiang, China's western most province, from Krygyzstan. The walls of the dining hall are hung with topographical maps of the Northern Areas and various glacier crossings. A board to the right of the kitchen door is covered in postcards, most from Germany, most written by tourists with more money than time, their comments share what a lovely stay they had. The length of the hall is hung with rugs, goat horns, antique photos and more maps. A hotel guide recommends I look up sketches of the hike in the comment book. Guests have tried to outdo one another, the Korean and Japanese have each filled the page with the skill of an anime artist. The French, German and Swiss are much simpler, another European has drawn the chain of mountain peaks like Russian dolls.

I keep the sketches in mind next morning setting out with

a light backpack. Beyond the village, past a dirt track through sleepy fields, lies the bridge tucked into a V at the foot of the mountains leading to a steep series of switchbacks of loose stone. The trail slackens and cuts into a forest of sweet smelling junipers, eventually reaching a small plateau where ahead the tip of Minnapin comes into view and the village of Hindi below in the valley on the far bank of the Hunza. Ultar peak climbs into view behind the western peaks in clouds cloaked like a scarf caught in the wind. The trail grows less discernable following the murmur of a creek along a ridge hiding the glacier from view. At the halfway hut three ladies from Singapore, their guide and a team of porters and donkeys unload several tents, cooking equipment, utensils and tableware, drinks, three chickens and surely if I wait long enough, a kitchen sink. I refresh with a cold Pepsi and carry on following the guide's direction to simply follow the trail beyond the junipers. The trail shortly scatters in all directions following goat paths crisscrossing the boulders and narrow spaces between the shrubs. I bound up the mountainside aimed

at the ridge above. until halfway I spy the trail on the far side of the crescent slope. I whack through the brambles and zigzag higher and higher meeting the trail near the ridge.

Two hours above the hut, I mount the ridge to discover the glacier stretching several kilometers before me, its black and white series of ridges and crevices descend from a distant peak to the north west and slide into close view where they turn abruptly below Rakaposhi, towering to my right, its peak hidden in cloud, and slide towards the village of Minnapin. The last few hundred metres are reached along a narrow and precarious path above the ridge, mud and loose stone, before dropping into an oval shaped bowl formed by the ridge and the mountainside. The bottom of the bowl is a long strip of pasture where two enterprising campgrounds have sprung up among the trickling water channels. The weather is chill, the air misty. I erect the tent, boil a pot of tea, then climb the ridge to admire the view. Only the hillside across the glacier remains unveiled, cloaked in fall colours, bright yellows and blazing patches of red. Far off

where mist and snow merge, two ants of men cross the glacier, racing the rain that has begun to fall. An hour later, after the cows have returned from the higher pastures, the two men pass my tent. They are friendly guys, from Karachi, on a one week holiday. The larger of the two, Ali, is the leadre of their six man team. Kazim, a handsome unmarried police officer is their cook. I am invited to join them for mutton later in the evening. The cold settles in, the rain picks up and I tie my boots on and wander down the pasture to the evening's feast. I'm welcomed by the younger members, three college students, light by a single candle flame. I take a seat and enter the conversation. We joke about the cold. I am served a leg of mutton and rice, unsure how long ago the meat was cooked, considering the rain has been falling all evening. Dinner is followed by strange riddles and magic tricks and card tricks.

The meat and the cold affect me rather poorly. I wake too late to a mess in my underpants requiring an awkward change in the freezing night

air. I shiver the rest of the night until swallowing a painkiller and feel my body start to overheat. The shivers return until I take another pill. The rain soaks my tent and the stamped earth is turned to mush and puddles. My stomach groans. At the slightest hint of day light I relieve myself among the rocks with an explosive force. The sky has been swallowed in dense fog and freezing mist. I collapse my tent, intuiting that I will only fall more ill should I stay in these cold wet elevations. The trail below the ridge has turned to muck. I slip several times. I'm forced to rummage into the bush to relieve myself several times along the descent. I know the trail ahead and encourage myself to plod on, having to pause more and more frequently until I can go no more than a hundred metres bewteen rests. I am unresponsive to porters ascending the trail and oblivious to the village children's friendly hellos. It is warmer in the village whereupon reaching the guesthouse I collapse in the orchard to catch my breath. The rest of the day is spent in bed, waking for a bowl of

milk porridge, only to return to sleep that evening. All the while I must visit the toilet every half hour.

Recovering in Paradise

Karimibad A quiet chubby man among the hotel staff gives me a lift next morning down to the KKH. Mid village we are stopped by four men. Their serious expressions and the driver's insistant refusals communicates a stressful encounter, a gang pressuring a fellow villager to join some kind of agreement. "Tension, tension," I overhear the driver repeat to the small but imposing gang. Even in Minnapin, a seeming paradise, there lies tension. A suzuki honks behind us and the driver uses this as pretext to bid the foursome adieu. On a bend in the highway I soon board a minivan north bound to Aliabad. From this unkept armpit of a town I catch a suzuki up the hillside to Karimibad, the jewel of the Northern Areas, formerly known as Baltit and currently known as the hub of tourism in Pakistan. I've arrived the end of the holiday season, mid September, and the row of shops and restaurants appear unpatroned. I book into Karim's on the cobbled slope below the fort. In one guidebook I

read, "Karim's offers the best rooftop views in town." I fail to read the later edition, "Karim's is looking tired and in need of repair." The weed garden is full of empty bottles, a wing of the guesthouse is off limits, the hall piled with timber and carpentry equipment. My loud calls fetch the owner, a muscled young Punjabi who leads me to the second floor row of rooms, where one room's key appears to work on all four. Luckily I'm the only guest.

At the owner's insitence, by afternoon when I have regained some energy, I catch a suzuki down to Aliabad to the clinic. The walled garden is a pleasent surprise. I admire the sign posted in the garden, 'smoking is injurious to health'. After registering I'm lead to a verandah where I queue on a bench full of middle aged woman and one elderly man. The doctor calls me into his light green office and take a seat on a stool between him and a plain clothes nurse. "We'll have to take a stool test to check for bacterias." A poster on the wall identifies a dozen microscopic bacterias. In the last twenty-four hours I have

passed too many

motions as the doctor calls them. My blood pressure is low and I am to be hooked up to an IV, something I grew accustomed to in Japanese clinics. If my body doesn't respond to the mineral drip, I'll have to stay the night. However after three hours of straing at the fan and its reflection in the IV bag, like a drowning mosquito, my bp level looks normal and I am discharged. Leaving the walled garden, I return to the suzuki depot but violent shivering takes me and I climb into the first available taxi. I shiver the whole ride and well after I have put myself to bed and pulled the wool blankets tight. When he asks if he can be of help, I tell the owner I'd like a bowl of soup. "Sorry, kitchen's closed." I'll pay you whatever just get me some soup. I can't move. A few hours later a knock at the door announces the soup's arrival. The young man asks if I have a candle then returns with one glued to a small table. The Hotel owner enters after lugging a large gas lamp and extinguishes the candle. A third

man arrives with a large basin of unspiced chicken soup. It's an effort to eat like they show sick people being spoonfed in the movies. An old man looks in the door and flips on the light. I turn off the gas lamp. Less than a minute later the generator escapes a loud sigh mid-chug and the room is thrown into darkness. I leave the soup for breakfast.

I return to the clinic next day for a blood test and discover I am normal. I've seldom considered myself normal but apparently it is now medically confimed. In the vicinity of the guesthouse, the carpet shop owners, the chapatti baker, the cafe owner, the young server, the three men who run the local eatery, have all learned who the traveler is staying at Karim's. "How are you feeling?" they each ask me throughout the day. I recognize some of them from the soup fiasco the night before. "Still weak today," I answer them. The next morning I slowly resume my tai chi and can feel the stiffness and exhaustion like a bike left out in the rain. I brave an omelette and late morning challenge myself to a short hike

up the crest in the hill to Baltit Fort. The cobbled road through the remnants of the old town is steep but not as much as the fort's entry ticket. I join a five person tour group in a carpeted room where everyone's admiring maps hung in frames. The tour guide, poor fellow, has a strange accent, a mix of all colonials mispronouncing odd syllables and misintoning others. Are his jokes his jokes alone or do all the poor tour guides share the same discourse. In the second room he explains how Islam was brought to the Hunza who retained their wine making traditions nonetheless. Gourds, which the guide refers to as pumpkins, lie about the wine making room. We're treated to a slide show; Part I, the Mirs, of whom only the last six have their image recorded in history, that is, since the British arrived in the mid nineteenth century. The current Mir has no special power. He's an elected MP with a mannish wife responsible for several womens' causes. Part II follows with snapshots of the mountains proceded by part III, slides documenting the fort's reconstruction. The tour passes through a maze of rooms, the largest of

which stands at the base of the stairs, its floor cut with compartments, a pantry in which to store the grain, tribute of the citizenry. The rooms on the second floor are brighter, the walls cut with windows looking onto the polo ground and valley. The tour does not include the Mir's sleeping quarters nor his wife's. I'm dissapointed to learn there is neither prayer room nor quarters for the livestock. The rooftop offered the most memorable scene in the tour, a view encompassing the valley from _____ peak in the east to Rakaposhi in the south. I recall this scene from a BBC documentary but the TV screen did not manage to successfully illustrate the length and breadth and superlative wonder of this valley. How could this valley fir in a TV screen! The guide explains how the Mir used to reside on a dais beneath this ornate rooftop pavilion before his court seated on the floor. In view of such a wide and varied and far reaching history and set in such an incredible landscape, I can't help but think the media is truely shameful for villainizing Pakistan.

Below the fort a sand bank along a water

channel leads into a shaded neighbourhood. A suzuki scrambles past. The sandbank is a road apparently. Men gather under the trees and chat, wives toil in the garden, apples weigh down the boughs in the orchards and bumble bees explore the tall fragrant flowering bushes. The ochards lie behing ditches or high rock walls, the branches carefully trimmed so not to be in arm's reach of passers by. I call to a young boy playing among the trees. "Yessir, he responds, "how many apples would you like?" His polite and formal English is as shocking as his well parted waxed head of hair. He approaches me with a pair of differing colour. "The golden apple is considered the more beautiful but the green is more tasty." He's right too, it's much juicier. Young children walking in threes and fours, in scruffy uniforms, collars unbuttoned, pockets torn, ties a skelter, stop me in the road, "one picture?" They laugh at their images. Soon I've archived the whole neighbourhood. One young boy already a man at eight years, golden hair neatly combed and freckles is determined to have a copy of his photograph. He has posed several times, has argued with his

friends to move out of the frame and give him his due, has caught up to me thrice, short cutting through the orchards, hurdling the walls I imagine while i take the gravel road's wide turns. In Urdu, a foreign language to him so I ought to understand, and strangely I do, sort of, that he wishes I should speak with a guide or with his school teacher for their ought to be somehow some way that he can have his picture. I admire his perseverance and feel his frustration. Life is tough,

the haves and the have nots, life's ultimate frustration. I ask him for his school book and a pencil which he delivers from his little blue and red backpack. I crouch on the roadside and the boy stands still before me ignoring his friends giggles and nudges. I sketch his friend with the sticky out ears, copying his young round profile more easily than his serious friend who I've drwan too angular as though he were already a teenager. I am asked to sigh the sketches before my comission is completed and they follow me to the main road and bid me farewell.

I've assumed a

routine in this hilltop paradise, focused on lounging and eating and admiring the views. Early afternoon I read on the verandah of my room to escape the midday heat. Incredible how the skies have remained clear as soon as I decsend the mountain tops. From three o'clock until sunset I can be found at the corner table in the garden of Baltit Cafe. The menu is a little pricey but rightly so, real estate like this where I come from belongs to snobs with high regal - keep the riffraff out - hedges and no starbucks could ever afford such an address only jeopardize their advertising behind a tall hedge. Admiring the view, reading my books, writing my journal, I order an apricot shake and a chicken salad and cheese sandwich with fries and contemplate each day to sketch the terraces and diatnt peaks. But how could you fit this valley in a sketchbook! Sean appears one afternoon in the cafe's garden, sniffing my trail from Chitral to Gilgit to Skardu, although its not a scent you can miss. He is quiet while we listen to the travel tales of an Australian, Roger and Tania, his partner from S. Africa,

Chapatti

Chapatti

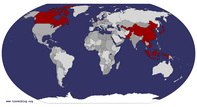

get 'em while they're hotwhom had shared with me the morning's Baltit fort tour. Roger's voice is beautifully crisp like a radio announcer, his beard is reds and browns and overgrown, slowly merging with his chest hairs. Tania's voice is pleasing too but i say this of most South Africans. As she said on the tour, we had first met in Kalasha but so many vistas later it was hard to place them. The days are spent like this; reading , writing, relaxing, and eating back the five kilos i've shat down the side of Rakaposhi. Since I'd last seen Roger and Tania in Kalasha, they had acquired a visa and been safely conveyed to Khabul. They complained of the heavy police presence and lack of freedom for tourists, cursing the stupidity of the Korean missionaries whose attempt to convert the Taliban cost the Korean government over a million for each of its misguided holy rollers. I keep my comments to myself. We laugh and laugh at the many strange things Pakistanis do, the stress of it all washes away.

Half past six as the sun peaks her crown over the eastern ridges, Sean hollers up to me on the verandah. I like

copy this beard please

copy this beard please

Handsome Young Carpet Salesmanpunctuality. We set off through the old town below the fort and cut into a back path leading to a water channel balanced precariously along a steep cliff face frowning across a chasm at an equally jaw dropping cliff, the two of them meeting deep inside the chasm where Ultar glacier feeds their water channels. A bridge leads across the tumbling waters. Sean follows my lead, confirms my direction which, after several falls on a steep shifting sand hill leading to a wet track among tall dewy blades of grass, has mistaken us. We backtrack. And despite the warnings of the guidebook, we follow the waterchannel into the heart of the chasm rather than risk our lives on a goat path over a blind horizon - so steep are the cliff faces. The rock face rises several hundered metres and drop as far below. We reach the tumbling current where it drops into the channels. Sean and I look at each other dumbfounded. Where is the path? Rock pile after rock pile block any view of the meadow we are after. We grow anxious to find the path knowing once the sun climbs into the narrow canyon, the river flow

will rise and block our way back. Across the rapids above the rockslide reads a painetd sign on a flate rock face, 'Ladyfinger restaurant 40mins'. We find a somewhat safe place to leap across the whirling glacier water, scramble up the bank and find the path at last. It takes more than eighty minutes but beyond the last rockpile we enter a high pasture where a stone fence encloses a few grazing calves. Further into the valley stands a lone structure of stone, 'Hunza House welcome', reads a sign above the doorway but after wrenching the door open, we find it empty. Roger and Tania appear crossing the pasture above us, returning from the morraine below the glacier, the latter looks like a frozen waterfall. The four of us complain there are no cold drinks on offer. Roger and Tania vanish back down the trail while Sean and I lie exhausted basking in the sun munching apples and walnuts before descending. Following our friends' advice, once the channels are reached we hang a right following the opposite cliff face. It leads to stunning views above Baltit fort and the Hunza valley stretching towards Minnapin. If it weren't for the monotonous

cuisine, relentless black flies and the over abundance of simpletons, I'd carve myself a home here in the mountains.

That afternoon I take my first honest to goodness 'motion' in over a week. Though I feel recovered, I continue to enjoy my vactaion from my vacation. I don't feel the least bit compelled to day hike or explore the old villages or millenia old rock carvings, lakes and glaciers scattered up and down the valley. I continue to lounge about Karimibad, enjoy the over priced menu at Baltit Cafe, the curries and grungy atmosphere of Rainbow Cafe, the communal dinners down at Hunza View Inn and most everyday I splurge on a chocolate, biscuits or cheese - yes, there is cheese in Karimibad, a cardboard roundel with a cartoon cow, a processed Swiss cheese called Happy Cow. Spread on chapatti and topped with french fries creates a delicious alternative to the club sandwiches. The other foreighers to Karimibad don't seem to stay more than a couple nights, lodged below the village in a string of cheap guesthouses. I shop the market for hats and postcards and compare kilims, exchange my books and sample local music. One afternoon I step

into the shiny little barber shop for a shave and a cut. I pass the place a dozen times each day and, surprisingly for such a little village, the seats are always occupied, the scissors always snipping. Both barbers are working on customers garbed in yellow smocks staring at their reflection, a cricket match plays on the TV, Sri Lanka versus Jamaica. I don't know a thing about cricket. I take a seat on the bench between two young men and wait my turn. The power cuts, the TV screen goes blank and the fan overhead slows to a halt. There are two showers in the back, both in use, until a man steps out from the curtain to towel his hair, finding space in front of the mirror and combing back his dew like an extra in Grease. The barber on the left pauses to pick his nose, examines his findings, before retrieving his comb and scissors. Luckily the one on the right motions for me to take a seat. A burgundy smock is thrown across my front and velcrod in the back. I notice goat droppings among the hair piled underfoot. I show the barber a photo from

my camera of a handsome young carpet shop salesman whose beard I'd like to copy. The salesman seemed flattered at the time and neither the barbers nor the other patrons think it peculiar I've brought this photo. There were other handsome parts to the salesman but I thought it better not to photograph these. In the cupboards above the mirror along three shelves stand a dozen red apples lined in a row alternating with packets of one of two ointments, an aftershave with flowers printed on the package and a pink box, its contents a mystery. The cut is quick and painless, the barber refers again and again to the photo. He lathers across my bristles an invisible sticky paste and sets to with a clean blade copying the carpet salesman as best he can. I pay 100 rupees, a buck and a half, for the experience. Another foreigners steps in as I hop off the stool. Do I tell him, the one on the left picks his nose, the one on the right has terrible breath.

I treated myself to more than just the rootbeer and cheese and chcoloate in Karmibad. In Islamabad I'd not had the time and elsewhere in Pakistan, the choices were slim, but in Karmibad a whole strip of carpet shops crowd the market. A distance from fort chowk's souvenir shops I discoivered, Hunza Carpets, a large boutique with gorgeous wool and silk carpets hanging from the walls and rooled up in piles about the floor, still others underfoot and small side room stocked with donkey bags and camel bags. I spent two hours admiring the wares, the senior salesman unrolling and piling and rerolling, narrowing down my choices, comparing colours, patterns and dimensions, while the younger salesman cross referenced the codes writtenb under each carpet with the prices in a log book. I settled on nine pieces in the end, four square mats, 4' X 4', "eating mats" used by the nomads, with simple geometric patterns in hushed tones of green, grey and dark blue, a larger rug in soft grey and eggplant and four donkey bags that make for ideal double cushions you can prop against the wall. Including shipping I plopped down a grand, a big chance to take. ( I can happily say the carpets arrived on schedule at my parents' place a month later.)

Khunjerab Pass There are few days remaining until I must enter China and validate my visa. I hail a suzuki down to Aliabad, passing Sean along the road, "See you in China!" I call. He yells back he has found the infamous espresso machine and homemade brownies of Northern Pakistan, Cafe de Hunza had closed and moved into a small cafe at the bottom of the village. No matter, I'd already gained back the five kilos I lost after Minnapin. Aboard a minivan I am Sust bound, passing numerous little villages along the KKH, and picturessque bends in the river. There are only three of us, including the driver, headed beyond Gulmit where the sunshine and early autumn colours and glaciers near Passu deserve more than just a passing glance. I later hear from Christine, a Swiss traveler, of her amazing few days stay in Passu, where she'd lodged with a local family who refused payment, the man of the house guiding her across the slopes and glaciers. Just before dusk the minivan pulls into Sust, the last village of the KKH and no more than a couple hundred metres long, the shadows disguising this whole in the wall as somewhat enchanting. Stalls set upo along the curb sell fruit and drinks and fried potatoes and crispy fried mysteries. After booking a ticket on the next day's Natco crossing, I fetch a bag of samosas and pakhoras and take them back to Sky Bridge Inn to enjoy on the verandah, admiring Karan Koh, a peak to the southeast somewhat like the Matterhorn, disguard its blanet of sunshine. A man climbs above his second floor home and, face lifetd to the sky, calls out across the neighbourhood, "Alllllah O Akbar. Alllaaaah O Akbar." A fellow living not far below him is interrupted from his TV show and steps outside his tiny flat to see what in the blazes his neighbor is up to.

9:00am sharp twenty passengers, among them a Swiss, two Japanese, two Poles and the rest Punjabis are assembled in the gravel lot in back of the Natco office when a tiny white hatchback pulls up spilling out three large officers in grey and navy uniforms. They step onto the stage, the passengers scramble out of the way trying to figure the next move. The largest officer points to a skinny weasel of a man commanding him to tidy the stage. It only makes the scene all the more farsical, tugging on a stubborn scrap of paper caught under a table leg. "You, please come, you are the biggest," the chief officer points at me. I hand him my passport while the other officers have me unpack the contents of my rucksack. We are an hour precisely before all twenty passengers have filed through and we can board the bus. 10:00am we cross the street to the immigration office, unload and file one by one into th office to have our passports stamped. At half past our bus crosses the checkpost at the north end of town, 86km to the Khunjerab Pass via Khunjerab National Park. This is by far the most expensive coach ride in Pakistan, tahnks in part to the contact with the Chinese and their inflated prices for independently traveling foreigners. Even the fellow who placed my bagf atop the bus asked for baksheesh. I refuse but Mireille, a woman from Basel on a 2 week holiday hands the man 20R. The road winds through an ever narrowing valley opf yellow and red trees. Approaching the pass, a keen eyed passenger spots a herd of ibex grazing on the slopes, a cross between a goat and a gazelle with beatifully large curving horns, probably over two feet long. The Khunjerab Pass is a long table top plateau flanked by the rounded peaks of the Pamirs to the west and to the east, the young sharp contours of the Karakoram range. At 4733m, the panorama is breathtaking.

Advertisement

Tot: 0.134s; Tpl: 0.023s; cc: 12; qc: 40; dbt: 0.0527s; 1; m:domysql w:travelblog (10.17.0.13); sld: 1;

; mem: 1.3mb

MikeandNancy

non-member comment

Envious at Home

Your writings and photos are wonderful Kevin. Thanks very much.