Advertisement

Published: September 15th 2007

The Valley of Old Storytellers

The Valley of Old Storytellers

a mid day hike above Madyan looking south east toward FathepurThe Sound of One Hand Shaking

The third century Buddhist sites and museum's trove of Ghandaran stone capitals, busts and architectural pieces occupy a few hours in the late afternoon. A hike into the hills of Saidu Sharif next morning is complicated by a lack of posted signs and easily rectified by a young boy who sees me poking around a rocky outcrop, also the roof of his neighbour's house. "Bukhtara?" he calls to me. He leads me back down the path skirting a gully and we turn up a road to a bluff concealing the remains of a mid-sized monastery. Stone bases and simple masonry walls slowly take on their surroundings, the walls slowly decomposing, the red earth crumbling anbd shifting with each heavy rainfall. I decline an invitation in Mingora to visit with two college professors and tour around the valley. Hospitatlity in Pakistan has meant little time to myself, time to gather my thoughts. Udyana Hotel, tucked in a market off the main throughfare, is a meeting place of the city's entrepreneurs and the educated. Every few minutes, I am shaking new hands. In the reception lobby, dining hall, on the terrace, I

am joined by the Hotel Owner, Uncle, as he is known to the younger men. Wearing cap, spectacles, neatly trimmed beard, he speaks English and tells me of his work abroad. His friends, a banker, a PTDC chair, a forest management deputy, an agriculture ministry worker, tell similar stories. They and others without stories ask me the same questions. My answer is an alarm sounding every ten minutes. "Canada - Kevin - English Teacher". There is something unsettling in Mingora. In the evening when I'm setting off for dinner, perhaps the place I'd seen just across the street, the hotel falls into darkness with a sudden and familiar sigh. It is not safe to go out says the hotel manager. At his insistence, I wait until the power has been restored and am accompanied by two young men, one who speaks rudimentary English. They accompany me in search of an internet cafe. In the thrid cafe, I succeed. In booths behind thin black curtains, young men chat on-line and look at images of naked women. An electrical strom up the valley lights the nioght sky with flickering bolts of divine force. I feel a slight charge on the souls of

Ali, the old hippy

Ali, the old hippy

hotel owner, drug smuggler, dealer in precious stones, international lover, heroine addict, & honey shop ownermy feet. The racket of chinqis and busy shops drowns out the thunder.

The manager of the Hotel guides me himself to the bus depot, a large courtyard off the main road festooned by dozens of mini-vans, busses, pick-ups jostling for space. All the colours of the world turned a dusty brown in a loosely organized melting pot. I squeeze into the back bench of a paki-van. When we are seventeen young men, three boys, one woman and two chickens, the driver sets the bus in gear and honks his way towrads the exit. When I was twelve, boys called each other Pakis, a derogatory remark. And the Hindu marking, the bindi, or third eye, we termed a Paki dot. I can't recall whether or notI understood Paki meant a citizen of Pakistan. Certainly I knew nothing of its history towards independence and its very creation, in opposition to the Hindu third eye. A Paki-van refered to the overcrowded Econolines I'd seen transporting men in turbans out to the farm fields. I only saw these men from a distance, sewing seeds, picking potatos. I never viewed them with scorn. They lived together in extended families, in colossal houses of

Ahamdilul

Ahamdilul

Ali's friend since childhood. Never learned how he lost his right arm.concrete and stucco, a Paki palace. My father considered these a blight on the landscape. I accepted his truth, his preference for the old farmhouses, steep roofs, attics, wooden shutters, wrap around porches. More and more of these concrete Taj Mahals appeared in the farm fields, often set inside high walls. They became a natural part of the surroundings, a piece of the mosaic that is Canada.

So here I am squeezed into a Paki-van. The road up the Swat Valley is more so the idea of a road, a thin strip of pavement down the middle eaten away at teh shoulders, forming potholes and mounds of rubble. The weather and tread of tires returning the smooth surface to its base materials. The river comes into view, a frothing, playful, greyish blue dancing across miles and miles of rocks and bolders, bathers and fishermen. Twisting, winding, accelerating, breaking, a steady stream of passengers hop on and off the Paki-van, blaring its horn at slowpokes, at road hogs, in blind turns of the road, in towns en route. The boy next to me leans forwards, his face hidden in a plastic sack. He and his brother in the bench ahead are

sick in unison. Their mother, her head wrapped in a black shawl keeps close to the open window. The young boy passes a plastic bag of sick to the fellow next to the window. I can't suppress my laughter but I offer the boy some of my mineral water and wet a handerkerchief I show him to press against the back of his neck.

Madyan Ali & Ahamdilul

It takes a little exploring of the hillside above the bazaar to find a guest house. A young girl with dark eyes answers my knock at the door. She returns with her grandfather who welcomes me into the courtyard where a sign reads, Check in and Chill out. He leads me into a spacious bedroom set behind a covered terrace. I join him on the carpet, enjoying a few pieces of ocra eatenb with torn pieces of a thick unleavened bread. I'm offered a tin cup of homemade lhassi. His name is Ali. He speaks calmy and quietly. It is his son's guesthouse. Ali owns a shop on the outskirst of Islamabad selling honey. He used to run a hotel in the market street here in town thirty years

back when the hippies considered Swat Valley their new found utopia. Conversation turns to hashish. I'm going to enjoy my stay here.

Do you like fishing, he asks. A grey haired man joins us, Ali's lifelong frioend, Ahamdilul. His name is something out of a child's storybook. He wears a mustard brown robe and a smart squaree beard and white embroidered cap. We climb into a packed mini-van and ride to the next village where we purchase fishing line and hooks. It's a beautiful afternoon. The billowy clouds grazing the mounatin toipsare unlike any I've seen, their shadows are dark green giant sheep roaming the terraced hillsides. We follow a road through an apple orchard and take a foot path to a fenced yard surrounding a raised one floor building with a brown wrap around covered porch, King Ashoka Palace reads a sign propped on the wrought iron fence next to a satelite dish. I shake hands with two young clean shaven men seated watching TV in a small room off the porch.

I follow Ali and his buddy around the back to Ali's room. His friend who owns the place has asked Ali to mind the place

house, Madyan

house, Madyan

interesting how homes and their inhabitants reflect each other's likeness and personalityfrom time to time, try to stir up some business. I sit on the bed and leaf through a guidebook printed fifteeen years earlier with nostalgic shots of faces and famopus sights of Pakistan . Ali prepares a charas, first heating a ball of hashish the crumbling it into a mixture with tobacco, and finally scooping it from his plam into the emptied cigarette. Ahamdilul licks and rolls a sheet of glossy paper. Ali points out to me that his friend's right arm stops at the elbow. Strange, I hadn't noticed. He is so dexterous with his left. He carefully places a light cigarette on the table's edge pinched under the coffee table's linoleum top. A pressed ball of dark green hashish is placed on the burning embers. With his paper tube, he leans over the smoke and inhales long. He laughs in a raspy cough. Ali laughs and passes me a spliff. I will remember this moment, these two men, the hotel, the thin green carpet, the perfect day. They stand and begin raveling the fish line around a stiff piece of folded cardborad, tying the hooks. We follow a windy path down to the river where midafternoon the

sun bakes the rocks. We each find a comfy perch and cast the line below the strong current. Ali tells me a fish story. One time a man was fishing on this bank, he points up the stream, and a big fish caught his line. It almost tugged him in, man, but his friend cut the line. A hundred metres upstream a bridge spans the canyon far overhead. On the far bank groups of young men relax on shaded boulders below a restaurant sheltered by two broad leafy trees. Ali tells me of the hippy days in Swat. I think of my Uncle in long wavey hair and curly beard riding horseback through the pictures of a faded guidebook. I can feel the fish bite, their nibble discernable from the current's pull and the rocks' rubbing vibration on the line. The shadows begin to climb down the bank. We drop the line moving on to a shaded outcrop of rocks but after an hour leave empty handed. There are no fish biting today, says Ali, we'll return with a net tomorrow.

The Story of the Soma Flower

In a corner of the grassy yard we sit in lawnchairs

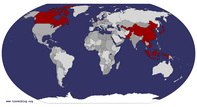

in need of cushions below a row of plum trees where we await the arrival of the hotel owner. The valley cools in the late afternoon shade, the sunlight climbing the eastern slopes. I admire the view to the southeast, a village nestled on the lower slopes of a protruding mountainside. We are joined by two men. Our circle stands to greet them. One of the men, dressed in a clean pressed sky blue shalwar-kameez and matching cap offers his hand and broad smile. He shines with a stroong sense of self possession. I wrongly assume he is the hotel owner and fix my attention on him, waiting to hear him address me in English. The man next to me is heavyset with a pointed white moustache and two more moustaches for eyebrows and hazel eyes liuke crystal quarz. He looks more German than Pashto. Upon learning that I speak French, he has brought a book with him, an atlas of minerals and gems printed in Italian. He is most eager to know the value of a stone labled labradorite, found in Eastern Canada, Scandinavia and Russia. It doesn't seem to be a popular stone. The men discuss gems, rubies,

fish for dinner

fish for dinner

Ali looks on as Ahamdilul's hearthrob of a tall dark and handsome son nets a catchmoonstones, topaz, turquoise, lapis lazuli, opal, onyx. I cannot shed much light on their enquiries.

The Hotel owner, as promised, tells me the story of this grassy river bank where we sit drinking tea and eating small red fruits tasting similar to dates. "When I first began this guesthouse, it was named the White House. I was shown a photograph by a German professor of Archaeology. It was printed in 1939. It was of this very spot and showed that there once stood a stupa built in the time of King Ashoka. He was Mauryan Emperor of Gandhara, now known as the Peshawar Plain, and a great patron of Buddhism, establishing monasteries and a university, establishsing the second great flourish of Buddhism since its founder, Prince Siddharat Gautama, some five centries earlier. You see that hill on the far bank, he points beyond the bridge. In the time of Ashoka, it was known as Junosat, place of the gods. On the night of the halfmoon the unwed women of the village would wait for the light of the moon to rise over the valley before crossing to the hillside. There they would cut a flower known as soma which

an old miller

an old miller

mills can be found riverside in every backwater of the country only bloomed in the moonlight. With the necetar of this flower, they woulf prepare a drink they offered to the 80 year old men of the village restoring them to the strenght of 18 year olds." I listen to the men in the cirlce talking in Pashto. Unlike Urdu whose syllables are quick and abrupt, Pashto's are longer and each syllable rolls into the next.

From the sixth century onwards the great Gandaharan empire fell to subsequent rulers with each passing century. The Achaemenid fell to the Macedonians under Alexander whose successor ceded to the Mauryan dynasty. Later the Bactrians, the Parthians and the Kushans each held sway over the region. I ask the hotel owner, Ataulahan, about the people of Swat Valley. The Yusufzai came from Afghanistan about five hundred years ago. They pushed the people out of this valley who have now settled in Kohistan, the valley to the east known in more recent times for its tribal feuds. The Swat Valley, once the northern tip of Gandahara, remained a Buddhist people well into the fifteenth century. From this time, the Mughals advanced into the region forcing Islam on the locals. Many Pakistanis will argue that Islam

was never forced on any of its followers, that the Koran explains that Islam is to be shared with others through teachings and accepted conversions. Islam of the book seems unlike Islam of the world. Swat remained its own kingdom even under Britsh rule. Ali shows me a coin dating to 1940 with the bust of Prince Al-Haj Sadiq Mohammed V Abbasid of Bahawalpur State. Not until 1969 was Swat annexed to Pakistan.

This young nation is veiled by the media in a deceptive burka. So little of the rich culture of the region and its many tribal peoples and their handsome crafts are known to the west. It was on visits paid to Vancouver's Expo 86 where I first discovered Pakistan through the colourful truck art, the floral designs, mountain landscapes, animals and mythical figures painted ion bright primary colours on shimmering tin sheets hammered between crisscrossing borads of engraved wood. I never understood these trucks in their true context, rumbling the crumbling highways they shared with Paki-vans. A young man in his early twenties running a successful internet cafe in Mingora, his clients cooled by a half a dozen fans whirring like giant hummingbrids, sat at his

Ali's old hotel back in the late 70s

Ali's old hotel back in the late 70s

now under new management and suffering terrible tourism. VISIT SWAT EVERYBODY! It's beautifulcomputer palying with a music icon, filling the room with an easy rythm. You like to chat, I ask, seeing a dialogue box on his screen next to a webcam shot of an Asian girl in denim shorts. He smiles. "What is wrong with Pakistan?" he asks. "When I am chatting and a girl asks me where I am from and I answer Pakistan, they immediately say good-bye." The veil over Pakistan blinds the outside world. Why not write, I live in a beautiful valley in the north of Pakistan. "Sometimes I write I am from Swatland," he grins.

Lights on the fence posts glow a dusty vanilla encircling King Ashoka's palace with a sense of comfort and dignity. Ali speaks to me in French. We cannot easily understand each other's accents. He continues with the tale of another German professor who following the text in a book published on the culture and geography of the Indus Valley and its surrounding areas, was most intrigued by a passage concerning a special type of mushroom. I've never heard of a mushroom tale, I confess. The professor was not a crazy man. He was well educated but determined to find this

King Ashoka's Palace

King Ashoka's Palace

Fatehpur, where no one would think to stop, and where I listened to the old men tell storiesmushroom. He read that it could give a man immeasurable knowledge, like a god. Ali's tale dissappears into the night, the German professor heading off to India occupied Kashmir on an invalid visa. I can hear merging with the conversation around the table, the call to prayer from two distant mosques. High on a bluff across the river in the light of a hotel's balcony musicians play to a small audience who clap a loud rhythm. A camera bulb flashes. A deep and resounding boom is heard to the south. I've heard similar sound in the time but the detonation finishes with more of a crackle sound when the hillsides are blasted for rock. The men all stand and quickly gather walk to the TV room off the porch. I follow behind. The men flick through the channels for news of what has just happened. The Hotel Owner is on his mobile, "hello, hello" his voice frantic. The line is poor. Ali tells me what I assume is still only rumor at this stage, that an improtant man, a sort of district chief has been killed. The Hotel Owner, Ali tells me, holds a similar position so he is naturally

worried. When I understand the gravity of the situtaion, I fell awkward and helpless, watching adverts for skin cream, tea mix and cell phones. The shiney happy houselholds on the TV screen don't ressemble any of the Pakistan I have seen. The power goes out and we shake hands goodnight. Ali, Ahamdilul and I smoke a spliff before heading up to the crossroads to catch a van back to Madyan. The road through the orchard is pitch black, my friends only slightly darker shapes in front of me. White streaks of light dance in the tree branches, dozens of fireflies, marking the curbside. A Paki-van pulls up after a few minutes and we squeeze inside. Ali scrambles on to the roof. Still others hang off the side and back rails. I can see the road ahead in a hazy glow. The dark night hangs to the edge of the headlights' beam. The van charges along its path, spraying gravel, bouncing over potholes and rock piles. Stoned, pinched under my arms between two young men, I enjoy a Paki-massage.

Ali's Only Story with a Happy Ending

It was an unintended sidetrack but I've been a week already in Swat

Valley, sifting what I see and read or what I'm told, stories of King Ashoka, of the Hippy Days, of Pakistan's struggle towards independence, news of bombings, confusion over Musharef, his police, Afghani refugees, rumors of revenge killings, General Zia's military takeover and suppression of President Bhutto, killings, failure of democracy. I sift and put in chronological order the many stories of Pakistan. Pieces are missing or fragmented, like most stories. On the main road, the only road out of town, at the south end of the market, Ali once owned a hotel. It was the sventies. America was waging war, participating in Vietnam's cicl war, giving cry to millions of protestors and the peace movement. Draft dogers, lost souls, drifters, peace loving hippies searched the world for their small bit of paradise. Ali's hotel had good business. He often shared the responsibility of its upkeep with the westerners. One English girl stayed eighteen months. And often Ali gave a roof over their head and food on the table to those who'd run out of money, letting themn earn their keep running errands. Ali speaks slow and hushed much of the time. "Hey man", "Mother Sucker", expressions he has learnt

icecream worth photographing

icecream worth photographing

I braved the ice cream (sorbet) machines only a few times as they are undoubtedly mixed with the tap water - but sometimes one needs a change from dhalfrom ghosts of an another era, hippies, Ali would be disappointed to see today, embracing capitalism. He tells me about the women, French, Italian, English, German, Canadians whom he's been close to long ago. Some were travelers to Pakistan and quite adventurous. Every weekedn Ali and his German girlfriend would ride the horses she'd bought in the market as a tourism venture for the hotel. You should've seen the faces of the other villagers, shocked and jealous. There I was riding atop a horse in the company of a western woamn.

Ali smokes heroine. Brown sugar, he calls it, a soft powder light brown to grey. He places a little on some foil he has torn from inside a cigarette pack and heats it until black. The fire heats the powder into a cohesive metallic liquid. Ali uses a tight roll of paper to inhale the smoke. I watch him out of curiosity the first time and because he is smoking it in my room out of sight of his son or daughter-in-law. If you smoke it, he tells me, more than two days in a row, you become addicted. I watch him smoke it each day for a

travel agency sign

travel agency sign

I thought first this was a call to arms against the USweek. It's okay, I'll be alright. I have none in Islamabad, he assures me, so I'll have to stop. I don'y judge Ali. I don't consider his finances and how he spends the little he has. He talks about an Australian he'd trusted with a precious stone. Last Ali heard, the man was in LA. Ali tried several times t contact the man but was never responded to. The man had promised to send half an estimated 2000$ profit.

In the late seventies, early eighties, Ali traveled Europe. Following the advice of an English sweetheart whom he's met in Pakistan, he had packed up and sold the hotel and his antique shop in the market. Business had been falling. He flew to the UK. When he arrived he called her. I've found a new man, she said, I have a new life. Please go back to Pakistan. Ali moved to St Tropez where he found a wealthy French girl. For many years he flew back and forth between Pakistan and Australia smuggling drugs, selling precvious stones or carpets. He spent over two years in a Paris prison. Once in Belgrade and once in Istanbul he'd been mugged. All his

market, Madyan

market, Madyan

the ever present Bedford truck, the first of which I saw at Vancouver's EXPO 86things stolen. "Two fellow Pakistani approached me in the train Station in Milano. I was waiting for the night train to Roma. I bought them tea and we took a walk together. A coffee, they suggested. I told them let's go back to the cafe. They said, no, the cafe people were no good. In the basement of the station there was a cinema but for some reason it was closed that night, people sitting or sleeping everywhere. The two men got out a small stove and cups and prepared a pot of strong coffee. I had one sip and was out stone cold for forty-eight hours. When I came to, I realized my train ticket and luggage ticket were missing. I just sat there, you know, thinking but without anything to think about. Several weeks earlier in Belgrade, a group of Pakistanis had approached me and told me their story, that they'd been robbed. They asked if I could help. I passed them eighty dollars. They each embraced me. They said they had money beiong wired from friends in Switzerland and promised they would pay me back. I could tell they were wealthy kids. I hopped the train that

night. The fellow in my cabin asked what those others had wanted. He couldn't beleive I'd supported their story. A month later, sitting in Milano station, thinking but without anything to think about, I saw the same group of Pakistanis and went up to them and told them my problem. They paid for my ticket to Roma where they were headed as well, put me up in a hotel with them but in my own room. They all shared another. They went to the shops and returned wityh new luggage full of new clothes." That was my favourite of Ali's tories. Have faith in others.

Family Feuds

Much of the time, when Ali was not talking about the good ole days, he was complaining about the others in the village. They marry young and have too many kids. They can't afford to educate most of them and the cycle continues. The families continue to grow but their land hldings do not, the property divided and divided again among sons and grandsons. Ali has worked at several jobs, abroad and in Pakistan. He has always sent money home. His wife had not known better and lent too much of

it to her father and brothers. Ali has had little to do with her or his in-laws for the past twelve years. She complained when he stopped sending money. His in-laws took him to court shaming Ali and his wife. Naturally, I was surprised when Ali should take me to visit them up the valley one evening.

We set out in the afternoon, following his good friend, Ahamdilul, to his house on the river. We smoked a spliff, drank some chai and watched his son catch small fish in the rapids with a throw net weighted down on the ends with small stones. Ali, his friend and I continued our walk up the river. The sun was setting. I'm not sure what were Ali's intentions. He wanted to visit a woman among his in-laws who was bed-ridden with a broken leg. After two months like this her husband refused to spend anymore on medecines she needed. One of the elder brother-in-laws greeted us along the road. I knew who he was before Ali explained. Lefty and I were shown into a room with three beds made of wood frames and teathered rope for mattresses. Members of the family would join

us, the younger ones eyeing me carefully. I watched through the open door to the yard where the younger children played. Little faces with big eyes would come inside the door's light watch me a moment, then run off laughing. Two boys played in the yard with a string and jar lid, pulling and easing the string, creating a buzzing sound. It brought an instant smile to my face. Ali returned to tell me thay have killeed a chicken for our dinner. So much for fish. Hot roti, boiled chicken with chili peppers, spinach and a plate of salted onions and cucumber slices are set on a table by the beds. We feast. Two adorable boys, eleven year old cousins keep me company, both seemingly innocent, wanting to sit closer and closer to me. One looks me wide-eyed straight in the face. The other props his knee against my thigh. They teach me to count to twenty iun Pashtu. Their uncles scold them when they try teaching me Arabic. The eldest man of the household, younger and stronger than Ali, but with a weathered face and bushy greay beard, rolls a charas. Its new for me how its perfectly acceptable

market, Madyan

market, Madyan

oooh, there's the National Geographic shotto smoke in front of young children.

Behrain On a trip I make on my own one day, repeating a short ride up the Swat to Behrain, fifteen ruppees of speed bumps, potholes, racing other paki-vans and taxis through breathtaking scenery. Ali had bropught me the first time. We'd hiked up one of the river cutting through town, flowing into the Swat, and watched boys leaping from boulder to boulder the splashing in the swift current. One boy's shalwar trousers had caught two large air bubbles. He floated over the rapids with swollen testicles. Three young boys cooked cobs of corn on the bridge, using a large wok filled with hot pebbles in which they rolled the corn. A man lead his two reluctant mules down to the river for a drink. Schoolchildren with backpacks prssed for home, following the river on a path behind us. On my second visit I followed this path curious to see where it would lead. I followed up the tumbling pools of cool water, past brick homes, stone huts apinetd white or left grey. That's a beautiful garden, I called to one man in a wool cap, a kontcha, decsending a ladder

from his roof into a walled garden. Tall pink and yellow and white rose bushes peaked their heads over the wall, relaxed in the shade of a few fruit trees. Someone had had the foresight to and skill to erect a walled garden within a small patch of land sitting between the river and a canal conveying water to the homes further off the bank. People everywhere, coming, going, working, playing, watching. On every road, every doorway, inside cars, on horse drawn carts, in the furthest reaches of the mountains, there are Pakistanis etching out a life for themselves. I'd thopugh to find a quiet place along the river and sketch. The path I take does not go beyond the farms. The valley up stream is reached by another path on the opposite bank impossible to reach without a long backtrack. I find a boulder amid the rapids where I relax a measured and inaudible distance from two youths upstream and a family downstream daring each other to submerge their eentire bodies. First the rocks, then the trees, grass, stone bank, the scenery takes on a black and white form. From the first rock drawn, I had a crowd gathered

around me. One boy sat next to me looking back and forth from the sketch to the river, noting which objects I was recording. He motioned to his friend passing by who joined us on the rock. The more firends, neighbours, brothers until the late arrivals had spilled onto the surrounding rocks. Flowing white and pale blues and browns, the boys' robes created a curtain I asked to be parted so I could see the scene I was trying to depict, the white house on the bank. More boys and young men gathered only to see through the crowd why others had gathered. Someone sparked a charas. I laughed to somebody that I could be selling cold drinks, making a little profit meanwhile. A man crouched next to me, perhaps twenty years old, said his name was Raven or something thereabouts but with a Pashtu's use of phlegm when pronouncing the r. Would I sketch him, he asked. He must've known he was beautiful, that he easily stood out in a crowd. I sketched rather poorly one side of the face lopsided with the other, nervous because there were so many eyes watching each pencil stroke. I took the 2B

and filled in his dark head of hair. I could do a better job if we were alone. You are a very handsome guy, I venture. I think back home you could have any girl you chose. It's strange. He wanted me to look at him, to study his face, the long wavy strands of hair, parted down the side, arcing across the top, light brown eyes, long thick lashes, a strong straight nose, a small upper lip, a thin strip of beard framing his jaw and chin, the cleft in his chin. Or he was oblivious to my emotional state and simply wanted a picture of himself. He knew he was handsome and that I'd enjoy looking at him. As payment for entry on the rock, I asked that another spliff be rolled for me. My request was granted. I'd finished the drawing but tweny or more boys remained on the rock, chattering, loitering, chilling. Raven asked if there was anything he could do for me. I actually wanted to be alone, I said. With a flourish of his hands the rock emptied.

And here the story telling ends

I've been in Swat too long, I start to

think, feeling too relaxed. I talk with Ali but otherwise I am quiet listening to Pashtu, trying to decipher the more commonly used expressions. When I do speak, my words sound strange to me. English sounds out of place, like a television set on a tropical beach. Then I hear the importance in each word, its picture a thousand words. I choose my words carefully. Ali and I move out of his son's guesthouse one evening. He hasn't been around much but suddenly he's calling Ali on his mobile. "The backpacker has left! Did he pay you? How much? That's not enough! Those prices were from last year." Ali and I move into King Ashoka's Palace. I take a room on the back corner with a fan and a clean white tiled shower. It's twilight and the week of the meteor shower. Ali and I share a spliff and I stay in the yard watching for shooting stars. There are other stories in the Swat Valley, the men seated around King Ashoka Palace garden pouring over the owner's rocks he is brought from his mine up in the mountains, the children who spend most of the day splashing in the

canals by the mosque in the middle of towen, the bee keepers, the farmers, the hippy days, Ali's shocking tale about the tourist who set herself up in Gilgit in a hotel and under the police's supervision earned a fortune in two months sleeping with the men of the village. The stories end here, however, late morning. Ali and I have dined at his friend's on omelette and corn bread. My bottle is filled with fresh spring water. I wave good-bye from a Paki-van anbd sink my head into Benazir Bhutto's autobiography. She is 35, in England at last for medical treatment and protesting in America the US sponsorshipo of General Zia's junta in spite of their rampid human rights abuses.

From Fethapur the van travels down to Mingora along the west bank's broad valley, passing villages of wooden shop fronts and crowded chowks. Wheta and corn shine gold, rolling to the banks of the river. Midday in Mingora I cross town to bus depot and connect for the mini-vans to the north. I hop a van in the crowded game of vans, busses, passengers and cargo headed across the river for Chakdara. The police stop us on the

bridge. There is some confusion. Our van has pulled up just behind a tour group coach and the officers think I should be aboard their charter. Across the bridge lies southern Dir district. I fill in my specifics in their logbook. He is explained that I am a different nationality and traveling on my own. The landscape changes. The mountains lose their green peaks. Brown rocky slopes slip past. I'm reminded of illustrations of the Holy Land in my old bible from elementary school days. We reach Timargah, a small town where a narrow sloping road off the bazaar only just accomodates the van into its birth in the depot. Our bus and one other form two queues. The drivers call out, "Dir e!" "Mingora!" I slink into the shade of a teashop, sit next to the window looking over the market and sip my milk tea.

Advertisement

Tot: 0.316s; Tpl: 0.021s; cc: 26; qc: 135; dbt: 0.1879s; 1; m:domysql w:travelblog (10.17.0.13); sld: 1;

; mem: 1.7mb

Linda

non-member comment

I can't believe you are actually over there.

Great blog, Kevin. At times I worry for you and at other times I marvel at your spirit. Stay safe and keep the stories coming.