Advertisement

Published: April 25th 2018

E1E4D4AA-516A-427B-91B6-8345438D8FA9.

E1E4D4AA-516A-427B-91B6-8345438D8FA9.

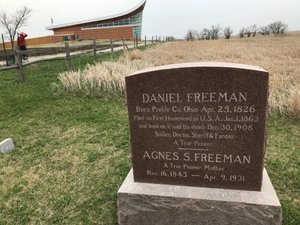

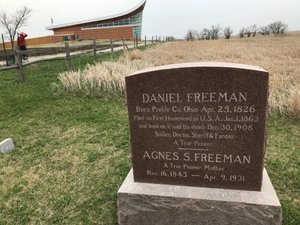

Freeman’s Gravesite - first HomesteaderHomestead National Monument of America, Beatrice, NE

In 1862, while the country was embroiled in civil war controversy, Congress passed and Lincoln signed, the Homestead Act. It was intended to serve as a kind of relief valve by siphoning off the disaffected and unlucky, including released black slaves, and send them into America’s hinterland by offering up free land. 160-acre parcels were available to anyone - all you had to do was build a home on it and farm it (they called that ‘proving it’) within five years of staking your claim. Over the next several decades, 160 million claims were filed, giving away one third of the American landmass in 30 states - pretty much from Indiana westward. (Texas was the only western state that did not participate in this rush). Although the portion of each state that was given away varied, in some states, like New Mexico, it amounted to about two-thirds of the entire state.

Billboards were plastered everywhere in the east and south advertising this new government initiative. And, something not likely to occur today, billboards advertising the action were put up in countries all over Europe and even in Latin America as a way

to attract immigrants. Some argue that this was one of the biggest reasons for the post-civil war surge in immigration. What could be more attractive than the promise of free land on which to build your family’s future! It was an integral part of America’s Manifest Destiny to conquer the entire North American continent.

Like all promises, public and private, way too many are not met. A great deal of unsettled America at that time was on the Great Plains. And what people didn’t quite understand about the Great Plains was that there were few trees out there, water was sparse, and, although the soil was good, it was not an easy place to build a house, cultivate a farm, and raise a family. Only 40% of the homestead claims were actually ‘proved up’ within the mandated five year period. Still, it is estimated that some 93 million current Americans are descendants of homesteaders. And the self-sufficient mythology that goes with that drive, is a huge part of the conservatism of the American mid-west and west.

The very first homesteader, filing his claim in the wee hours of January 1, 1863, was Daniel Freeman. And his homestead was

131615C9-8414-4B3B-ACF9-FD2F71C138A6.

131615C9-8414-4B3B-ACF9-FD2F71C138A6.

Cutout is proportion of state homesteaders.located just four miles west of Beatrice, Nebraska. His original log cabin, and the subsequent brick house he built himself, are long gone now, but the monument here preserves his 160 acre plot. The monument is also an attempt to restore and preserve the original tall-grass prairie, the ecological system that homesteading eventually wiped out, replacing it first with plowed furrows, and now with giant crop-circles watered by center-pivot irrigation systems, owned and operated, increasingly, by mega-corporations.

The monuments visitor center, ‘Heritage Center’, is designed to look like a plow and it sits on top of a hill overlooking the freeman Homestead. Inside there is a museum filled with exhibits on the causes and effects of homesteading, tracing its history from the origins of the act up until the last homestead claim, by a guy named Dierhoff who filed his claim in 1986 for a plot of land 200 miles west of Anchorage Alaska. On their computers, they have records of millions of homestead claims and you can look up your families records to see when and where yours might have been filed. The film at the center is one of the better park service films and gives a

very balanced view of what happened.

Outdoors, you can walk the perimeter of the homestead, viewing up close a restored natural tall-grass prairie system and walking over and around the sites where his homes stood. Part of the walk takes you near Cub Creek where he got his water, and through a cottonwood and burr oak forest where he was fortunate enough to find wood for lumber. There is something monumental (sorry) about being on the spot where it all began. This is certainly worth a stop if you are anywhere near Southeastern Nebraska.

Things aren’t all happy here, though, and the film and museum do a good job of exposing the raw underbelly of the Homestead Act. The biggest problem is how the act ran roughshod over the Native Americans who lived here. The justification for the government to sell off this land was that they owned it, (most of it anyway), by buying it from the French government, i.e. the Louisiana Purchase. But as one of the Native American voices says in the movie, ‘it wasn’t theirs to sell!’. Yes the French claimed all of that land, and sold their claim to the U.s. government. But

why was the French claim considered legitimate? They had never purchased it from the natives, and had never even negotiated the rights to all that land. So by what right could they sell it?

Part of the ‘misunderstanding’, if you want to be euphemistic about it, is that Native Americans don’t really have any concept of ‘owning the land’. For them, it makes as much sense to say someone owns a chunk of land as it does to say they own a chunk of air. Land isn’t property, it is simply part of the process of living. Native Americans have a life-sustaining relationship with the land - they don’t ‘own’ it. If anything, the land owns them.

So they were quite mystified when other folks started occupying their homeland. Homesteaders might show a piece of paper ‘proving’ that they owned the land and that made as much sense to Indians as some of the other claims of ‘western’ mythology. Eventually, though, the U.S. government had guns, and native Americans didn’t. So the final result was not based on moral righteousness, but rather raw mortal power. And native Americans were driven off onto weak, useless land parcels, often in

Oklahoma, where, with little natural resources, they get criticized for not ‘succeeding’.

So like most of ‘history’ there are good things and bad things. But I am glad we made this stop. In addition to the history lesson, there is also the prairie ecology to appreciate. I bought two books and finished half of the ecology book last night. Might write some more on that subject later.

And this completes our travels in the great state of Nebraska. There were only three bucket list items here, and we did the two monuments in western Nebraska on previous trips. So, unless we live long enough for a second round of travels, we are done with Nebraska and will be moving on to Iowa (in the rain) later this morning.

Advertisement

Tot: 0.097s; Tpl: 0.012s; cc: 11; qc: 32; dbt: 0.0689s; 1; m:domysql w:travelblog (10.17.0.13); sld: 1;

; mem: 1.1mb

Jane

non-member comment

Additional Books to read:

I read Conrad Richter's 3 books, The Trees, The Fields, The Town, many years ago & it was an eye opener, as to "Our History". Not sure these books are still in print; bought mine in a used book store on Oahu, of all places. Love reading/following Yours & Joan's adventure! I appreciate all areas/aspects & information shared through your eloquent writing. Safe Travels to You, Joan & Your Pups!