Advertisement

Published: October 19th 2007

The Natco Express

Shandur Pass The Daewoo bus pulls up nearly an hour late following a restless night in which the wind and rain lash the apple orchard releasing the fruit to drum on the tin roof. Leaving Mastuj, I am the fourth passenger in a coaster that seats more than twenty. My rucksack is hoisted onto the roof rack and I take a seat up front to enjoy the vistas out the windshield. On the town's edge where the road starts to climb the Laspur River I am made to register at the checkpoint. We pass a series of villages tucked among trees crowding the road. Dozens of school children are hastening their way in pairs and small groups, in uniforms befitting their grade and gender, anticipating the morning bell. Across the river along another road commute their classmates. The bus halts continually. Old men and women, young couples, families, their hands held out to hail the coach, followed with roadside embraces, and well wishing, climb aboard and dump their sacks in the aisle. When there is no standing room, I make for a space in the back bench and squeeze in. The bus zigs and zags up Sor

Laspur, a hidden triangular valley of yellow-green tucked among triangular mountains of blue-green. Entering famed Shandur Pass, the valley spreads out beneath brown rubbled peaks. In the distance a shimmering lake lies next to the Polo Grounds, the white stone bleachers, now deserted, offer little evidence of the merriment and excitement of 6 weeks back. The bus comes to a halt before a couple tents erected on the grassy knoll above the road. Passengers alight and wander onto the grass searching a stone for themselves behind which to squat, lift their robe to relieve themselves of their morning pot of tea. The officer of the tent wears a thick black beard, black sunglasses and a khaki uniform with beret. I sit next to him around a table where other passengers sit smoking and drinking chai. Descending the other side of Shandur Pass, the valley now flat and marshy, follows a meandering creek home to grazing cattle and horses. The valley tightens and heads eastward, the creek becomes a shallow turquoise river.

Phandar I'm let off in Phandar, a row of simple brick store fronts, four kilometres short of my intended night's stay at Phandar Lake. Unwilling to lug

my belongings, I settle on a simple hotel in the back alley of the village, a brick rectangle painted in a solid green Mountain Dew advertisement facing its blue Pepsi neighbours. I join a group of middle aged local men seated eating the everpresent dhal and rice in an alcove in front of the hotel. Through an open door, an equal number of young men stirring milk tea, baking chapatti and bringing a pot of dhal to boil. The owner shows me through the dining hall to a door tucked in the corner behind a table. I haggle the price down to 250rupees (4$) including dinner and breakfast. The afternoon leads me along the technicolour river in search of the lake. However the brambled bank and marshy pastures direct me back onto the main road. "Hello!" "What's your name?" "Asalam Aleikum." dozens of school children stream along the curb, watchful mothers and neighbours in tow. "Picture? Picture?" I oblige them and try to instruct an extatic gang of prepubescent boys and girls to stand back and not hit each other, let everybody inside the frame. Men lead donkeys back to the farm, packing firewood. Women, their heads covered in patterned

Lahtbo

Lahtbo

the hiking stage that wasn'tshawls, crouch in the furrows picking vegetables. The road climbs a rocky clay bank lending a view over the valley, a blue ribbon woven among patches of green and yellow, tinted brown or blue. Beyond a ridge, below a steep landscaped bank, I discover the lake, no larger than an Olympic sized pool and shallower to one end where horses and cows munch in the afternoon rays. I find a tractor's path back along the riverside and two young men dart from their yard to greet me. I am offered candies and told that this valley is nicknamed "little Kashmir". Chickens squabble, roosters crow, cows communicate their deep satisfaction relaying messages to old friends and family up and down the valley, MMMOOOOO! Children holler across the river, "what's your name? What's your father's name? what's your brother's name?" I cross the bridge and continue back towards Phandar. Two men halt my progress with an invitation to tea. I'm lead along a stoney creek to a huddle of hillside stonewalled houses and terraced vegitable patches. The older gentleman nods good-bye to his friend and hops across a channel into a thicket of poplar trees. The younger man, a mathematics teacher, invites

Herlighoffer base camp

Herlighoffer base camp

the hiking stage that wasn\'tme through a wood door set in an earthen wall. The interior is dark. I follow him deeper inside to a four pillared room layed with carpets and cushions, constructed under a clever skylight, its frame built of overlapping beams. Behind the posts, painted with Chitrali script and simple flowers diagrams, the walls are lined with beds. His mother joins us. Her complexion reminds me of sun dried tomatoes and her breasts sag below her waist under a purple polyester print. A young boy and a baby girl join us next. Grandma watches the baby doesn't hurt herself.

My host, Bulbul Amanshah, offers me a plate of apricots and answers my few questions about the valley. Most of the inhabitants are Ismaeli, a more liberal sect of Islam, who follow their religious orders not from the Koran so much as from their leader, Prince Karim Aga Khan, whom they accept to be the forty-ninth imam descended from the Prophet Mohammed (peace be upon him). Throughout the valley, from Chitral to Gilgit, north into Hunza and further east into Baltostan, white rocks have been placed high on the steep hillsides in characters reading, "Golden Jubilee Mubarak" or "Welcome Hunza Imam".

camp fire

camp fire

only shot of the sly porter and the donkey boyOn the 11th of July earlier this year, their Imam celebrated his fiftieth year as religious leader. For saftey reasons he lives in Paris from where he delivers weekly sermons, or "farman" and coordinates a society for the development and wellbeing of the Ismaeli homeland. Blue signs posted along the roadways tell of the Aga Khan Society's schools, universities and clinics. It is already dusk when I leave my host, both of us greatful for the visit, and wander on to the hotel. The manager has set off in search of me but soon returns, laughing at his own worries. I dine on yak with a couple men visiting the town on business.

Gilgit The Natco bus pulls into Phandar on schedule, packed. I gesture to the conductor, may I sit on the roof with my pack. A wise decision, allowing me unsurpassed panoramic views of the most beautiful two hours of the valley. Two other men grip the luggage rack with me, passing me biscuits and old smiles. Towering rock faces, crashing rapids, tall swaying poplar trees and small villages settled into the terraces, fringed with rocky land devoted to cemeteries zig and zag along the road.

Cars honk to pass as the coaster halts and passengers board and alight. A single Natco bus is the only public transport each day. The road cuts into the rock face, heavy cliffs jutt overhead. I'm later told in Gilgit that I was fortunate, moreso than a French man whose leg was broken riding atop the bus when a falling rock crushed it. Tractors block the road shoveling remnants of landslides caused by last week's heavy rainfall. I'd heard stories from a backpacker who'd traveled the pass following heavy rainfall and along with the other passengers was made to walk through the section of landslides until they met the bus blocked from the other direction. The bus passes scenic Khalti Lake, a widening of the turquoise river created by a flood twenty years back. The edge of the village actually lies below water. The bus stops for lunch in a town covered in dust like an antique sepia print. The wind and sun riding atop the coach have upset my stomach and the plate of pasty rice smelling of camp fire seems rather unappetizing in the fly ridden cafe.

Beyond the Ishkoman Valley turnoff the valley widens and loses

its peaceful charm to a series of towns and villages clanging with simple industry. I sign in at the checkpoints as we approach nearer and nearer to Gilgit. My first impression is of the heavy police presence in Gilgit, hub city of the Northern Areas. Tribal clashes had ignited concern in the late nineties and again a few years back. Rock or cement bunkers have been erected at intersections, officers and soldiers wielding automatic weapons watch the traffic. The lowering sun lights the surrounding mounatin peaks in a golden whipcream. I trudge through town, at a loss with my map, ask directions every hundered metres from the aforementioned soldiers. I tour most of the town before finally discovering the guesthouse, tucked into an alley on the edge of the market. A backpacker's oasis of "budget tour packages" and bland dishes "cooked fresh for you" welcomes me from behind a tall iron gate among a garden of roses. I'm invited to sit and enjoy a welcome cup of tea. I wake with the sun and find a quiet corner of the rose garden to practice tai chi before ordering breakfast in the front garden's dining quarters. Most backpackers are headed out

early, fetching flights, mini busses or coaches to destinations near or far, north to Hunza, east to Baltostan, south to Rakaposhi or east to whence I'd traveled from. I spend the morning drinking tea, nibbling chapatti and digesting the semblance of an omelette, engrossed with my current novel,

Maps for Lost Lovers, by Nadeen Aslam.

I leave the refuge of the roses and the tale of the missing lovers and their quarreling families for a day hike along a dried up water channel high above the bowl in which Gilgit lies. A boy of 18 years in snug fitting polyester track pants sees me passing up the hill from Serena Hotel chowk, a suburb of Gilgit, and approaches me, asking my destination. He joins me or rather guides me above the houses to Jutial Nala, the narrow opening of a steep hike into the forested slopes hidden beyond. Correcting him, we guide each other to the water channel, where he continues with me a distance from his village. I learn he is one of three sons, his brothers studying in Karachi while he studies engineering in Gilgit. You must be from a wealthy family, I tell him. His father's

Chakchan Khanqa, Khaplu

Chakchan Khanqa, Khaplu

oldest mosque in the village, either 200 or 400 years old depending on whose story you're tolda farmer in a village in nearby Naltar Valley. The young man boards at his Uncle's. He is Ismaeli and speaks Chinar, one of a half dozen tribal tongues, whose roots differ as much as Pakistan's neighbours, and are all heard spoken in the streets of Gilgit. The boy's face is smooth like an apricot, easy, unoffensive with the trace of a moustache. It's wonderful how 18 year old boys shine, on the verge of manhood. We walk on together alone high above the valley. I wonder why he has joined me but assume it's only summer holiday boredom. I tell him I intend to reach Kargah in a few hours time and show him that I have come prepared with a small picnic. He says good-bye, we shake hands and he turns back.

The channel hugs the mountain side several hundered metres above the town. I watch the streets and traffic and compare it to a mental picture of the town map. A loud revving leads my eye to a thick band of pavement hidden beyond a row of trees where a plane is taxiing to take-off. I watch it accelerate down the runway and soar over the

valley, at eye level, then vanishing to a speck. I meet a new channel, this one flowing and servicing a community of small homes set in walled gardens. Women go about their washing, children splash in a large water tank that should probably have posted signs against such activities. I pass a teenage boy with a rifle propped in a tree. I don't bother to stop and ask why. I reach another village further on and descend rather than follow the channel into a tight valley headed away from town. "Kargah Buddha?" a chubby young boy asks me, as I pass him following a dirt track. I nodd and he points back where I've come from. I backtrack and see above the road carved on the rock face a standing Buddha figure. But below the bend in the road, far more interesting in the heat of the afternoon, a small creek spills down a lush narrow ravine. I find a rocky perch and soak my smelly feet. Five young boys call from the road and with enthusaistic gestures instruct me to join them for a swim. They direct me to a pool in the creek created by a small damn

of rocks. We all peel off our kameez and jump one at a time into the chill waters, our shalwar bottoms ballooning with trapped air. The eldest boy is the most reluctant until I splash some sense into him. His brother, the youngest by four, five years shows off in a series of acrobatics. My old swim coach tendencies has me trying to teach them butterfly in a pool less than five metres across. Instead we try to outspin one another in a somersault competition. I hail a suzuki back to town. The driver stops not far along next to a spring and with one hand holding a jug filled with water, he sprays the doors and tires, with the other hand he smokes a joint. I explore the bazaar the rest of the afternoon, fetching a bag of fried orange potatoes and spicy beef kebabs then investigating the wears on display in the psuedo antique shops. The salesmen unroll their kilims, "this from Afghanistan, Turkmenistan, Iran. This one very old, this one from Yak's wool." Thank Allah, I'm not a salesman or a shopkeeper.

The Sly Porter & the Donkey Boy

Nanga Parbat Packed up, porridge downed,

bills paid, I hop aboard the 7am van bound for Astor. Seat #6 is a half seat next to the sliding door. Beyond the city's perimeter past the checkpoint, zoo and firing range and just before the road narrows dangerously through a construction site that has piled boulders on the shoulders, 'PWAM' pops a window off the back left side of the mini van. The driver doesn't appear the least bit surprised. He slides it under the seats and we continue. The Karakoram highway (KKH), the ninth wonder of the world claims a stone plaque, follows the west bank of the Hunza River charging south. On the far bank villages sprout on a fertile bluff. At Jaglot, less than an hour out of Gilgit, the Hunza and the Indus collide in a wide sparse valley of primordial rock faces and heavy sand piles. The Karakoram and the Hindu Kush face each other from either side of a battle of plate tectonics. The van zips past a few villages skirting the highway, shops selling grapes and apples and creating detours at which passing vehicles feel inclined to honk. A quiet side road dips down into the gravel beds and crosses a

bridge over the Indus and up the narrow canyon of a tributary.

The Astor Valley circles around the back side of Nanga Parbat, the second highest peak in Pakistan, ninth in the world. Small terraced villages cling to the roadside and step halfway down the canyon. Astor, hub city of this small valley and once gateway to Baltostan and Kashmir lies four hours outside Gilgit. In the journey's last hour my stomach pains return. I gallop down the road and take a turn off up the hill to a series of hotel sign posts. I enter the first guesthouse, the cleanest looking. "Can I use your toilet?" There are few uniforms in Pakistan. I have no idea if I'm talking with an employee or a guest. No response. The small crowd of men seems fascinated with their own tasks. I race to the neighbouring hotel where i'm shown to the john. Occupied. When I have my chance at last, I am a symphony's percussion section. The half full jeep, I'm told will take me the last hour up the valley's end to Terashing, sits idling on the roadside where a burning pile of rubbish sends a plume of smoke

through the open window. The drive is slow and agonizing. Each stone finds its way under the wheels. My stomach senses each one squeezing thru my intestine. The man seated at my side introduces himself as an employee of the hotel in Terashing and passes me a business card for a terkking company based in Islamabad. I ask if he'd seen my friends pass through town the previous day, an English woman and her Chinese husband. Yes, he nods. He has told three lies but my attention is focused inward on not letting fly a second symphony. He pays my fare as I dash into the hotel's courtyard and hunt down the toilets.

The Hotel owner shows me to the second floor rooms where he explains there are fine views of the mountain at sunrise. I am the only tourist in town and get the room for a quarter the price. In a cozy lounge tucked between the rooms I watch the pink clouds of sunset. I take tea and later am served a plate of chicken and rice in the glow of the gas lamp. Two men enter and introduce themselves as the local police. They inform me

that the fellow who rode in on the jeep with me has signed himself up as my guide. I'm stunned. I tell them I hadn't agreed to that. Besides I can't afford a guide and request only a porter. The officer explains that they have already contacted the main office in Astor so it's best I take this man.

This man whose name is never told to me has returned home according the Hotel Owner. The foreign bacterias coursing through my intestines and the circling dialogue take their toll but we come to an agreement.

The man shall be my porter and I shall pay him the respective wages, 290 rupees per stage. The return trek to Shaigiri covers six stages and takes three days.

The peak of Nanga Parbat and the glaciers and mountain chain that fall to its northeast are slowly gilded with the first morning light. In the courtyard, out of view of passing shepherds, I practice tai chi, breathing in the fresh apline air. At breakfast the officers return accompanying

the man who is to be my porter. An argument ensues. He believes he is entitled to a guide's wages. I argue that he speaks

less than 12 English expressions and the trek is through an open zone. The officers defend my statement and

the man conceides. Not a hundred metres up the trail, he has me wait while he fetches his walking stick, a bag of oily chapattis, a few groceries and then proceeds to hire a donkey. A teenage boy helps set the load on the beast's back. We cross the first obstacle of the journey, a lateral morraine separating Terashing from the next village, Rupal. The donkey and the teenager follow the porter and I. It appears my porter, despite our agreement and his wages, has disguised himself as a guide and the donkey boy as my porter. The latter brings up the rear, with pursed lips, making quick fart noises, urges the donkey over the loose rocks.

Atop the ridge of the morraine, the view looks out across lower and upper Rupal to the next glacier crossing. The steady ascent cuts through terraced fields where men and women, stooped in the grass are cutting and seperating and standing the hay in bushels. We pause for a juice at a general store tucked under a shady tree to wait for the

donkey boy to catch us up. Young boys play in the next yard a game of volleyball catching it on the roof or in the tree branches with every other pass. A handful of teens loiter in front the shop watching me closely. A handicapped member among them sits at my side and inspects me up close. Above Rupal, donkey in tow, we follow a footpath through green fields along a water channel. The guide-porter leaps a fence and I follow through a jigsaw of stone huts, their doors no more then three feet high. The dark brown track climbs steadily into a lush damp glen, the grass munched short as a golf green by the beasts who journey to the summer pastures above. We skirt a pond and I have to watch closely not to squash a hundred wee frogs leaping across my path. Into the second morraine, I lag behind admiring the views up to the glacier. On the far ridge, two shepherds are erecting a cattle fence. The porter and I take a load off while the donkey crosses the undulating rock path. Continuing on what had seemed a wide expanse of flat green meadow is in

fact a field of small mounds, moguls made of grass tufts. Beyond one more glacier, or rather the rock slides left in its wake, we descend onto Herligoffer.

The donkey is unloaded and we recline on a grassy patch by a clump of pine trees. A man in a chai brown shalwar-kameez and red baseball cap appears from behind the trees and greets the porter-guide. The former play with the dial on an AM radio while the latter takes my pot to the river to fetch water for tea. Another shepherd toting an AM radio sidles up. The first shepher jokes with me, "your guide speaks good English. You like lhassi?" he asks, pulling a 2l bottle from his side and pouring a cup. Many things pass for lhassi, milky, watery or porridge like. My cup is of the milky persuasion but too sour to finish. Chapatti is just as varied, thin like a crepe or thick as a doorstop, toasted and hot, cold and stale or oily breakfast pakhoras. I erect my bright orange one man tent before venturing out into the pasture, ie. to find a hidden place for a dump away from the skiddish yaks and

some yaks have all the luck

some yaks have all the luck

( the only handsome shepherd I encountered )sheep. On the hillsides, the treeline grows thinner and thinner hacked for firewood without much thought to reforestation. In many parts of Pakistan this problem is now being addressed and farms have been planeted with tight rows of poplars. I return to find the porter and the donkey boy preparing a pot of byriani over a crackling camp fire. Digesting my meal, I gaze up at the starry night sky but it doesn't hold my attention like prime time tv and I am early to bed. Rain drops split splat on the tent before falling in a regular pitter patter. My tent unzips and the porter's hand reaches in, "light", he calls.

Within minutes of sunrise, the sky clouds over. "Nanga Parbat doesn't like to show her face to foreigners." I hear this remark on two ocassions from different locals. We finish breakfast, a couple chapattis fetched from the shepherds' huts, and gather up our gear. "Shaigiri," says my porter, "one o'clock." I look to the time and understand that it will take five hours to reach our next night's camp. We set out circling the pasture along a winding river's rocky bank and a lonely grove of miniature

trees before crossing to the other bank. Overcast and cold, today's terk feels uninspired. Beyond a dusty brown bluff, a second brige brings us back to the north bank where rising a hill we start our descent into a small bowl where a clump of stone huts and piles of firewood face a low wet patch of grass, a reluctant gurlgling spring. "Shaigiri," the porter points to the huts. I'm dumbfounded. The five hour hike stopped short at forty-five minutes. "Nanga Parbat south face," the porter points to a cloud covered fock face, "Rupal peak," completely hidden in clouds and another peak further up the valley unseen. The prospect of lounging around this damp bowl doesn't much appeal. We have another pot of chai and I perch on a rock sketching the huts while the other two munch on chapatti. An HB pencil records the row of stone hovels, dark doorways, bundles of sticks, dirst, grass, shrubs, a grazing donkey, a rock slide and rock face and grey clouds. The return trek is done in silence, non-stop walking, the porter and I leaving the donkey boy at his own pace. Reaching the pond, the porter bounds up the hillside where

nature calls and I walk on ahead down through Rupal. The locals eye me suspiciuosly.

The porter finds me back crossing the morraine before Terashing. He whistles me over. I've followed a wrong path. At the porter's suggestion, I take tea in the hotel's little salon before dealing with his payment. Minutes later he returns apparently having changed his mind and requests the cash. I hand him 1200 rupees for four stages. He looks at me, at the money and back at me. He is confused. "Six stages." I fetch my guidebook and the hotel manager, standing nearby, I request to help translate. Last night we camped at Herligoffer, stage one. Today we hiked for forty-five minutes to Shaigiri, stage three. How is it possible that with a donkey we covered 8km in less than an hour and never set eyes on Lahtbo, stage 2. The hotel owner is slow to see my point and repeats several times to me that Shaigiri and back is six stages. When he begins to understand my complaint, he plays down his role in the argument. "I am only the hotel owner. This man is not with my hotel." One of the police

officers arrives, the one who cannot speak English. Before he has listened to a word of my story, he starts barking at me, "six stages." A bystander whom I've never seen before is pacing back and forth and shaking his head. I cut him off when he opens his mouth to me, "Look, you were neither on the trek, nor are you an officer, nor do you speak English, so sod off." I flick my hand at him. The Hotel owner looks at me pittyingly. I tell him I've had a great experience with Pakistanis up until now but that

this porter conned me. I pack up my room and apologize to the owner but I can't stay the night. I really don't feel relaxed there anymore. I pass the officer and the hotel owner the porter's wages for six stages, the latter having disappeared, before moving to the other end of the village to the recently opened guesthouse.

Once I've settled into my new room, I see the porter march across the lawn with half the men in the village in tow like dim-witted sheep. I'm stunned. "I've paid your bloody six stages. GO AWAY!" The hotel owner

Skardu

Skardu

a cinematographic moment from the hotel balconytranslates but still the porter doesn't leave. I share a few profanities with the porter whom though has swindled me I have still paid in full and still he doesn't leave me in peace. I pull him into the road and lead him back to the hotel where his money is piled on a bench in front of the kitchen door. "Sorry," he says. I leave without shaking his hand.

Gilgit After fetching a bowl of spicey noodles and a take-away order of pakhora I score a window seat on the early morning ride back to Gilgit. The first two rows arefilled with a family, including five women who keep their heads out the window hurling for most of the four hour journey. I have to time my picture taking carefully, sliding it closed before the next gague. Sunday. The post office is closed. My one errand is postponed. I lounge under a gazebo in the rose garden reading my novel, boiling myself a pot of chai and nibbling on chocolate biscuits. I have almost forgotten about the previous day's fiasco. A Scottish girl who's nearly lost her accent after two years of traveling the sub-continent and sounds

more like a BBC announcer, sits chatting with me while I scrub my laundry. Erica and her boyfriend Robin have been cycling across India and Pakistan wearing their shalwar-kameez, I learn, commenting that I could not picture them in spandex. Erica stands over six feet draped in a clean purple kameez. Robin is soft-voiced, with spectacles, snake like dreads and a long beard. I join them on the back patio and listen to an excited German, a tall young man with bronzed skin and turquoise eyes, discuss fuel cells and hydrogen and ethanol andalternative energy sources with Robin. I can't follow and doodle in my sketchbook. Erica pulls out a pipe and passes around a bowl of hash she managed to bring across from India. Late evening a gang of us head down the block to the best kebab restaurant in town. Pots simmer and bubble in the shop's roadside kitchen. Skewers barbecue over charcoals. Inside the tables are packed, all faces turn to gaze upon the foreigners. The air is smokey, the surfaces grimey, the fans whirl, and everywhere dart black flies. We are led upstairs to a family room where the six of us feast on two large

Gilgit

Gilgit

facing each other either side of the street, a sunni and shia mosque are much cause of the tension in Gilgit and the consequent heavy police and military presencebowls of meat, one of chicken karahi, the other mutton, all for less than ten dollars.

Baltostan At 730 I am the first to board the minivan. On the edge of town the van is filled at the depot and we continue down the KKH before taking a narrow highway east between red rock faces encouraging the raging current of the Indus River. The six hour journey is one of the more breathtaking in Pakistan, squeezing past over loaded Bedfords, near misses with Yaks, passing terraced villages and lazy roadside restaurants. The Indus suddenly widens upon entering the Skardu Valley, a kilometer in breadth and shallow forming several sandbars. In the rugged town of Skardu I have an hour to fetch lunch and groceries before the onward journey a few hours further east to Khaplu. The road leaves the Indus, the latter headed south then east beyond the mountains and into India, less than a dozen restricted kilometers away. We follow the Shyok River past hamlets tucked in lush gardens fed by an inticate design of water channels. It is nightfall before we reach Khaple Bazaar, with a cozy, rustic, end of the world charm. As arranged the

minivan driver lifts me up the winding roads to the village's upper reaches where I inquire for a room at KT Lodge. An NGO has rented out the entire lodge. I spend the night a taxi ride half way down the hill at an overpriced hotel popular with trekking groups. The hot shower is delightful however.

Morning, the sun is just rising above the Karakoram, shafts of light descending into the silvery river and the hamlets on the far banks of the Shyoke and Hushe rivers. The peaks of Masherbrum and Honboro remind me of the painted pictures in my old copy of Tolkien's The Hobbit. I enjoy the short quietness of early morning practicing tai chi among the rose bushes. At breakfast the calm is broken by uniformed children arriving to school. The slopes of Khaplu make for tiring walking but the complete lack of tourists, Pakistani or otherwise, make it rewarding. I explore the backroads and peak into the wooded yards, ambling along the water channels fed by the Gnanche river, a trickle of srping water which cuts a wide path of rubble through the middle of town. On the east side of town three old wooden Khanaqs survive from the 18th century. I admire the carved lintels and doorways with floral and geometric designs but am forbidden to enter the mosques. A barrel chested old man passing along the road reminds me with an unwelcoming authoritarian tone in his foreign words. Children playing in the street call hello, salaam, how are you, two rupees. In the irrigated yards figures move about their daily chores. Unlike most elsewhere in Pakistan, the homes are here painted in light geen, yellow, soft blue, creating a communal sense of culture and an appreciation for an improved lifestyle. The road winds up the slope past a polo field - they're to be found in any village of the country - and reaches the old Raja's Palace peaking over an earthen wall covered in dried spikey brambles.

Despite the cracks and holes in the walls, the edifice remains impressive. Thanks to my chance encounter the night before with the manager of the NGO financed by the Norwegian Government and responsible for rebuilding the palace, I am given a tour of the rooms. Naturally, it takes a quarter hour or more to communicate this message, the manager being on business in Skardu, but once I track down the English speaking foreman, the request is relayed to the chowkidar who leads me up the grand staircase and unlocks the imposing edifice. A narrow hallway where several hard hats hang on a carpenter's horse leads to a court open to the upper floors allowing the servants who inhabited the ground floor to hear their masters on the upper floors. I'm lead from one room to the next through low doorways too quickly to get my bearings. A narrow corner stairway leads to the second floor, crumbling wood planks lead to the third. A thick plank can be closed over the staircase to protect the Raja and his family. The chowkidar demonstrates how the guard would have locked the hatch with a strong beam fit through two iron handles. A low railing wraps around the open court. I'm shown the finest rooms of the house, the sleeping quarters for the Raja and in another corner of the top floor, those of the Rani. The ceilings in both rooms are carved with wood mouldings, painted floral designs peer through a cake of dust. The crumbling walls contrast with the fine wood lattice window frames which look across the village sloping down to the Syoke and the merging Hushe dominated by range after range of the Karakoram. On the roof top is a small pavilion where the Raja could seek some peace from his political and domestic affairs.

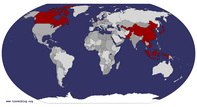

At the top of the village lies the oldest mosque in Khaplu, Chakchan Khanqa, a colorful two floored square surmounted by the elegant sweeping eaves of a tin roof. The surrounding homes and shops and children and wives seem oblivious to the poorly tuned blaring loudspeaker from the new mosque down the block. Forbidden to enter the Khanqa, a kind shopkeeper leads mer above the roof of his house where I can take a picture of the 400 year old structure. A dirt track leads above the village following the east bank of the Ghanche, flowing through a gorge, Ganse Lungma, seperating Khaplu from two picturesque terraced farming villages, Gharbunchhung and Hippi. The villages, some sixty dwelling altogether, perch either side of the river. I observe a mosque high above Hippi balancing on a rocky spur and make that my destination. A young girl dressed in rags hunched over her washing sees me pass and directs me up a rocky staircase from where water is flowing. I hike above the field strips until reaching a precarious water channel hugging the mountainside that leads me to the rocky outcrop. The mosque is abandonned and empty inside. The rock tower climbs a few metres higher than the mosque and provides a romantic place for a picnic. Three locals, father and son and grandfather see me toss my apple core and approach offering a heaping handful of nuts and dried apricots. I much on pistachios and drink in the view. I imagine where is India, China, Afghanistan, Tajikistan, beyond the mountain chains.

In the afternoon I change accomodations, sacrificing my hot shower for something affordable in the bazaar. The Citizen Hotel has no English signage. Locals point to a narrow footpath between two buildings. An open white door leads onto a courtyard tucked among the rooms and the corner kitchen/ reception. Two Punjabees are seated in the courtyard eating rice and dhal. Several other men are watching TV in the kitchen. The manager makes himself known and shows me to the VIP suite, the only room with a semblance of a pisser tucked inside a dank closet. In the bazaar, where cozy meets grubby in the dust and poplar trees, I enquire about transport to Kasumik, a village to the northwest up the end of a valley and starting point of a good three day trek. I'm given confusing news. I can take a public jeep in the afternoon but won't arrive til just before sunset or I can take a minivan to Doghani, first village in the valley and hitch the eight kilometers beyond.

I wake before the day has lifted its golden orb over the peaks. As the mini van leaves Khaplu we pass a Bedford lying in a ditch on its side like a slaughtered yak, its front end quite damaged. I am let off outiside Doghani, the near side of the suspension bridge and have a quiet one mile hike into town. The bazaar is asleep and the few people up and about tell me there is no jeep hire. I continue through the slumbering village, the sun begins to climb diown the slopes and light the corn fields. Outside the police station a sign reads, "Foreigners must sign in." I enter the wrought iron gate and follow the sound of a breakfast conversation, subdued laughter and the scraping of a pot. I arrange with the officers for a lift to the road's end, 800 rupees for a rumpy bumpy eight kilometres. The young officer plucks a few apples and slips them in my bag. The senior officer climbs in behind the wheel, smoking his thrid cigarette since I stepped inside the office. He smokes half a pack on our journey, aided by the junior officer using one cigarette to light the next. It would be generous to call it a road, the undulating gravel track to Thalle La. Several times the truck stalls and two young men we've picked up, hop out the back and help push. Eventually all the pushing and cursing and gear grinding doesn't help. The captain is replaced by a friend who leaves his tractor by the roadside and we manage to bump our way the last kilometers. In the penultimate village below the road on the edge of the wee village a mosque is being erected. Over a hundred locals have gathered in orderly lines passing sandbags, wheeling barrows, calling and receiving orders.

Three hours from Khaplu, a little more than thirty kilometres, we enter Kasumik, a hodge podge gathering of twenty houses. To my dismay there are only four men in the village. The officers lead me to the home of the youngest man who, the senior officer remarks, will be my porter. We gather in a room with two large windows and and simple carpets spread wall to wall where we are served tea and chapatti and yogourt. As is the custom in Baltostan, the men spoon a greyish brown powder, Sato, into their tea. I nearly gagued on a cup of this brew in the bazaar in Khaplu. I decline a second. The young man of the village proposes an unfounded fee as porter. He speaks no English and has no supplies, not even a sturdy pair of shoes but neither I nor the officers can haggle him down. We return to the next village where the circus of locals continues to construct their tower of Babel. Among the mayhem, the young officer returns triumphantly with a guide for me agreeing to a lesser fee, a guide old enough to be my grandpa. His name is Ibrahim. Reluctantly I load my rucksack on his back. His broad smile is familiar to all the village who wave him goodbye, the young kids shaking his hand. Shorty before noon we are back in Kusomik. We make preperations inside his home. His wife serves me yet another cup of chai while her husband races about searching for his sleeping bag which he shoves into a fraid canvas backpack. The trek's first couple hours follow an easy dirt track up a cultivated valley of gold and green patches inside rock walls. Despite his age, Ibrahim's endurance is as youthful as his smile. Shepherds leading goats and women returning to the village with loads of fire wood in whicker baskets greet Ibrahim and share small talk. Having set out late, we make camp four hours into the lower mountains at Metsik Pa. While I erect my tent on a grassy island in the creek, a shepherd collects the dry yak pies with a stick, tossing each into a wicker basket. The animal's feces are a good source of heat. An electric pink band of light streaks across the horizon before falling into darkness. After a big mug of hot yak's milk, the bubbling waters sprinting across the rocks lull me to sleep. All I've eaten today is tea and milk and chapatti but I'm too tired to be hungry.

The next day, fueled with another hot cup of yak's milk, we make for the upper climes. Our pace slackens as the temperature drops and the altitude stirs our heads. Yaks graze before the distant peaks of Honboro and Masherbrum behind us to the east. By early afternoon, bundled against the biting wind we reach the summit of Thalle La (4,572m). The descent down the west side across broad pastures is easily done, Ibrahim bounding ahead of me. Golden marmots stand at attention whistling as we pass. Bunking down for our second night on a short strip of level ground below the path, I give my sould a good massage. Ibrahim borrows a generoud amount of the cream to soothe his arthritic knees. I start a fire while Ibrahim stones a stubborn yak intent on sharing our meal. After his prayers we prepare a spicy pot of Biryani. The third and final day, a steady descent begins along a narrow donkey path cutting through a series of small pastures and shepherds' huts. Reaching Bauma Harel, the path slopes steeper hugging the cliffs of Bauma Lungma, a narrow dry rocky gorge. The path is ell marked, a beige ribbon of dust undulating into the distance. We keep a steady pace trying to reach the bottom before the sun enters the gorge and make Chaupi Ol by noon. I have in mind to camp here under the trees and have a look round nearby Shigar, a quiet village endowed with a fort, khanaqs and history not unlike Khaplu's. Ibrahim is anxious to return home, however, and seems intent on securing me a ride back to Skardu before he heads back up the pass. After tea, we saunter into Shigar, along dusty roads lined with trickling water channels. A group of young men outside a poorly stocked general store make room for us in their circle and keep us entertained until the muezzin is heard across the polo pitch and they clear off. Presently, a colorful flatbed trudges into the block. The equally colorful pirates in the cab make room for me. Rising over the pass, Shigar valley, in a blend of blue river, grey sandbank and green and navy slopes stretches north to some of the country's toughest glacier crossings. Adventures for another day.

I book into Baltistan Tourist Cottage, dark and dank and conveniently located over the bazaar on the main chowk. A buck fifty affords me a windowless single with an operable fan, squat toilet and pipe from which cold water fills a bucket in lieu of a shower nozzle. After a good scrub, I dawn my grubby crotch torn, hash burn holes shalwar kameez, in the process cutting my hand on the fan, and scour the market for a cheap bunch of grapes and a kebab shop. I know the prices and argue with the vendors confidently. The few men in the kekab shop watch a hung TV in the corner showing the news and music videos of scantily clad Indian girls. Strange how unalike these neighbours are, India and Pakistan. And on further thought, so many bordering Asian nations encourage their dissimilarities and bicker over undefined boundaries or wars of the last century. I find the owner of the guesthouse who is busy training his three young sons, like lapdogs close at his heels, the business. I receive admission to the oily cave of a kitchen and boil a pot of tea to enjoy on the balcony. The sons and a couple guests recline in metal chairs serenaded by a radio next door, watching the traffic under a fading blue light, a translucent and timeless dust grey-blue, until the stars appear, cueing the guests for dinner. Before that moment ends my uncomfortbale stool transports me to a cinema where the scene before me, an idle moment between plot points, is used to enhance mood and setting, two of the sons their chins perched on the balcony's rail and the nervous pacing of a tall stranger chating on his mobile. Sean appears in the dining room, a traveler from New Zealand I'd met a few weeks earlier. We share french fries and swap tales of misguided hikes and misfortunate stomach pains.

Advertisement

Tot: 0.312s; Tpl: 0.023s; cc: 21; qc: 136; dbt: 0.1638s; 1; m:domysql w:travelblog (10.17.0.13); sld: 1;

; mem: 1.7mb

Stacey and Mike

non-member comment

Wow!

Kevin, beautiful photos, WOW! You are such an adventurer, here we are with tickets to the Canucks game tonight!!! Ah, such contrasting lives we take as a step off from Hiro-ville. How long is your adventure, are you back to Japan or coming home to Van? We are awaiting your arrival! Safe journeys and keep in touch! stace xo