Advertisement

Published: August 11th 2008

Inevitable

Inevitable

This is bound to happen....shocking I haven't come across more...The taxi deposited me in front of the art gallery. My day’s travels ended in a thunderous and rumbling “Sir!” from Prashant when we made eye contact followed by a rib-crushing bear hug. Upon realizing how genuinely excited the gregarious Rajasthani Commando was to see me in Naggar, I knew I had arrived in the right place. The miles of over-the-road pounding had come to an end and I was in good hands.

I doubled back through Shimla because there were no connections across the mountain passes to the road leading to Manali. I would either stay a night in Rampur or Shimla. As much as I could do without Shimla, I could still go out, re-energize myself with a good meal, and socialize beyond the wee hours of nine in the evening. Strangely enough, I had no intentions of opening my notebook from Shimla to Naggar, the second half of the split journey from Kalpa. I wanted nothing eventful to take place and I was well on my way. That morning, I descended through the putrid back streets of Shimla, passing laborers painstakingly climbing in the opposite direction with goods for the vegetable markets. All the produce was stuffed

Up Front!

Up Front!

I got to ride in the bus cabin on the way to Kuulu...in burlap sacks, some five feet high and four feet in diameter. The loads of onions, eggplant, and corn were almost as large as those that carried them. Lines of men by the dozens ascended the slippery stairs without a word. Their steps were steady and extremely slow. How they could do this for a living day in and amazed silenced me. There was no access to the vegetable market except by foot. Upon depositing loads of a hundred pounds or more, they retraced their steps only to once again perform Atlas’ endless task. I asked myself silently: Why not move the market to where people wouldn’t have to break their back to haul such burdensome loads and risk life and limb? Why not install a pulley system? There has to be a better way, right?

“You!” he waved at me to come forward. “You, you come here now!”

He has to be talking to me. As with most situations with bus rides, I was the only foreigner aboard. I pointed to my chest to confirm. He nodded. The man never asked anything of me but to join him. I was already comfortable in a mildly functional reclining chair

Way To Go!

Way To Go!

Kiran spends more time with children than the adults...with a partial view out the window. I wanted nothing of importance to take place. Kewal, on the other hand, saw me as an opportunity to crush the boredom to which he was accustomed on a daily basis. He has been working this route as a fare collector for the Himachal State Transport Corporation on a pittance of a wage for the last six years. He offered me the best seat in the front cabin of the bus, one with upholstered padding. There was room enough to stretch my legs all the way across the hub of the engine, though I needed to be careful that no part of my legs or feet came in contact with the blistering steel cover that encased the moving parts. Through the floor I could see to the asphalt. Best of all, my face was never more than a foot away from the ceiling-to-waist level windshield. I privately enjoyed my false sense of exclusivity.

The thirty-five-year-old father of two spoke of nothing in particular. He pushed his limited English to the brink with standard questions I’d expect from anyone struggling to make conversation. Often I did not understand him. To the balding, mustached man

Art Exhibition

Art Exhibition

My Indian Mom travels to show off her art reflecting Rajasthani subjects and culture...with money pouch around his shoulder, it mattered none.

After crossing the Satluj, we stopped for lunch. Roadside eateries in India are dismal at best. Kewal pushed me to the back of the kitchen where bus staff eat. I walked through the earthen floor dining area of plastic chairs, soiled tables, and flies, and took a seat with Kewal at a folding table up against a mud wall. He ordered nothing and only asked in a perfunctory manner if I liked vegetarian. Sure, I said. Who doesn’t? In Himachal, vegetarian is always on the menu. I didn’t expect filet mignon. The diner’s owner placed in front of us three or four dishes of rice, dhal, spicy vegetables, and a phenomenal plate of stuffed chilies. Chapatti breads came in intervals of a few minutes; I do not recall often lifting my face from my plate or the serving dishes. Overall it was a top notch lunch. By surveying the hygienic conditions of the diner, I figured this would be the make-it-or-break-it final exam for the antibiotics I carry with me. If they pass this test, I’ll have to make a commercial for Ciproflaxcin. I reached into my pocket and stabbed for

Willing Subject

Willing Subject

She readily posed for me. Each of her expressions told a different emotion...some banknotes to pay. Kewal grabbed my hand and shoved it back into my pocket. “No, you are my guest. You no pay.”

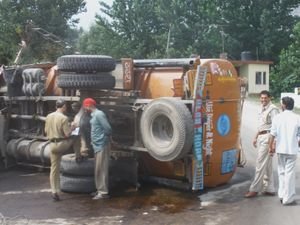

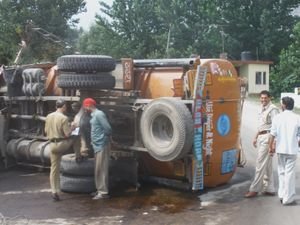

It was bound to happen. Motorists take absurd risks on roads not suited for the fits of vehicular insanity. So when we came bumper to bumper with the overturned fuel truck, I nonchalantly reached in for my camera and took some snapshots to document the event. Gasoline had seeped onto the road and was flowing over a cliff. The stench of fuel filled the air. Two police officers were filling out forms. A third had gone over to inspect the remains of a smashed van. I saw no one injured. From what I could gather, it is possible any victims would already be en route to a hospital. There was no yelling, and to my relief no lawyers passing out business cards. Calm controlled the scene. Our driver did not rubberneck, rather he deftly maneuvered the bus around the spill the and gathering crowd. We were soon gone.

Kewal insisted on writing me a letter in the future. Now that we had reached Kuulu, his day was done; I had one more tiny stretch before I would

Naggar

Naggar

From the Art Center...a small piece of lovely Himachal...get off at Patlikul and then board a small van for Naggar. In the morning, the soft-spoken man will turn around and head for Shimla to retrace the same route as the day before. Sometimes he takes a day off a week, sometimes not. I figured this would be the time he’d bum me up for money or some ridiculous favor to help out his daughter or some invented family member recently fallen ill. We stepped down the steps of the bus together and he placed his hand in mine. “Now we are friends. Thank you. You are good American.”

He confirmed the cash amount in his satchel, then took three steps to the regional office. Before I gained the first step to reboard, he had already turned around to wave goodbye another time.

Art is like wine: You do not need an advanced university degree in it to know whether you like it or not. But to be accepted in the artistic world, it sure helps. Kiran Soni has been an artist since she was a child. She has adored the sensation of pencil on paper and brush on canvas. I met her and Madhukar in Cambridge, Massachusetts

Roerich International Memorial Trust

Roerich International Memorial Trust

Children come here to draw, paint, sing, and act...a few months before I departed for India at an exhibition of her paintings. It was then when I realized that I had not only come in contact with a extraordinary artist, but an even more extraordinary woman.

I have come to Naggar to attend the launching of her exhibit, Beyond Strokes. Many of the portraits hanging in the exhibition hall are the same that went on her U.S. tour: aged men whose eyes are a window into the arduous years of life in Rajasthan and women in traditional dress tending to livestock. Like Prashant, Kiran also saw me crawl out of the taxi. She hadn’t seen me since I left on the overnight train to Bikaner to see the Chhalanis. In her restrained demeanor, she cracked a smile and gracefully shook my hand. “Richard, I am happy to see you gain.”

“I am happy I could come.” We both knew my plans would never have sent me to Naggar if it had not been for her invitation. She was appreciative that I accepted. “Where is Madhukar?” I spun around to try to spot him. There was no point.

“I am sorry, but he stayed back in Jaipur.” What? I

Towering Pines

Towering Pines

At these heights, everything is a beautiful as it looks, unspoiled...had so much I wanted to say. We could catch up and pick up where we left off. How could he do this to me? “There were meetings he could not get out of, but you should know he very much wanted to come. This is one of his favorite places.”

And for good reason. Naggar is a hill village seven or so kilometers above the Beas River town of Patlikul, a short distance that makes all the difference in the world. Up here is a laid back community of villagers, shop owners, herders, and apple growers. Above the fray, it is a clean(er), quiet, and scenic community among pine trees, shaded trails, streams, and mountains. There may not be much to do in Naggar, but I challenge anyone to find something wrong with it.

At the summit of Naggar is the end of the road: The Roerich International Memorial Trust, a retreat for established and budding singers, painters, writers, and musicians. It is a facility of galleries, a stage for performances, seasonal gardens, and studios where artists can practice their passion. It is an unostentatious setup that welcomes people from all backgrounds. The only requirement from the Trust is

Years of Ups and Downs

Years of Ups and Downs

This is when a photo surpasses what words can tell...that art for the sake of art must spearhead the reason for the visit or stay. Even after three days, I ran the possibility by the Cultural Organizer, Sherubaba, of remaining on and finishing my writing project here.

“Ah, so you are a writer!” This pleased him. In his eyes, it lent legitimacy to my being there and could bolster the Trust’s profile. “Very famous?”

“No.” Not even close.

“That is OK. Look, Mr. Richard, you stay here as long as you want. We have guesthouse for you where you can write all day. Like an apartment. But we ask of you, for our children, our students: You also teach them to write, like expert in residence. Do you teach? You know how to teach children, teens?”

“I think I can try.”

The man with the wavy black hair parted down the middle of his crown wanted me to extend my stay. Of course, I had already committed myself to traveling, but I will admit to actually weighing the option of staying on. “Then good”, continued Sherubaba. “Any time. You stay here. You see here, we have everything for you. Everything is OK.” He was right.

Kiran has arranged a

Highlight Of The Day

Highlight Of The Day

Even her Mom loved how she lookd in the dress...three-room apartment that suits me in spite of a few minor drawbacks. The thin floorboards to the upstairs unit creak loudly. Any movement I make will surely be noticed by the occupants below me. By early morning, perhaps six, the local Himachal woman residing in an adjacent home starts splitting logs to prepare a fire for the day’s meals. I have gone out to stop her and with much ire have wanted to tie her down, immobilize her in some way. Then common sense prevails: before I reach the bottom of the steps, it occurs to me I am armed with my clenched fist and she with an axe. So I insert my earplugs and resume my morning slumber. On the first night in the apartment, I disturbed the resident arachnid from its routine. It crawled out of the sheets of one of the auxiliary beds. I actually have no problem at all with spiders as long as we are on separate continents. Upon sight of it, I involuntarily jumped back to the wall and regained my composure. I witnessed the spider with the wingspan of a Lear jet swagger the length of the bed cover. I introduced my agile roommate to the bottom side of my sandal. It was rather dazed after its first interaction with my footwear. Its legs quivered, but its eyes still gleamed at me. Curiously though, following swipes two through seventeen, ceiling to bed, it had no reaction at all.

“Richard, come quick. It is time!” I checked the clock, a minute past eleven. I had been typing for about two hours and was keeping track of where I had to be and when. It wasn’t time. The ceremony was scheduled to kick off at eleven thirty.

I went to the door. There was Sherubaba. “What? Why? I am not ready.”

“You must come now, very quickly. Everyone is waiting for you. We are not starting yet. You must come now.”

“So let me get this straight, I need to hurry up because Kiran’s show is starting”, I paused and gulped when I realized I was in India and this was actually happening, “early?”

No sooner did I change into a polo shirt and khakis, rush down and take my position among villagers, press, and local officials, did Kiran cut the red tape to open the show. With no words to mark the occasion, the public pushed in to survey the oils and watercolors of Rajasthan, a day-and-a-half drive from Naggar. Yet for many, it was worlds away.

Kiran gets it. Asked to offer words of gratitude to the public for their attendance and support of the exhibit, she kept her comments in both Hindi and English short and to the point. No one enjoys listening to anyone rattle on about accomplishments and acknowledgements when the majority has come for an entirely different reason. Part of the opening ceremony was the lighting of a brass-colored candle stand from which wicks stick out of a small cup in the center. The public circled around the staff as Kiran lit the first wick to mark the occasion. She then called up others who played a contributing role in organizing the exhibit on her behalf: the curator, a Dutch couple who photographed and videoed the event for her, and a Lithuanian singer who was to perform later in the afternoon. She called out certain individuals by name. As each person approached, they took a candle from Kiran and lit one of the wicks until two were remaining. Then without warning, Kiran scanned the several dozen in the gallery, found me, and called out, “Richard, please.” With her right arm she motioned a path from where I stood to the candle staff. She held out the candle to me and directed me to light one of the last wicks.

I hesitated. I wanted to refuse as politely as possible. Why did she call on me? I had done nothing to help out. I wasn’t part of the Trust. I know next to nothing about art. In actuality, of all the people who had gathered to assist in putting the gallery together the night before, I did the least if anything at all. A Spaniard and a Russian labored to hang her portraits with fish wire. Anja and AJ, the two Amsterdammers, adjusted and positioned each painting when finally set on the wall. I tried to intervene, but wound up sitting in a corner for most of the evening trying to look important but failing miserably at it. As I recall, during a break for tea and snacks, I held my own. Besides this there was no reason for me to have been there. Until I finally invented an excuse to retire, I marveled at the beetles and other exotic insects that crashed onto the floor while the others pushed through until midnight.

Why me? The entirely gallery focused its eyes on me. There was no way I could get out of this. Camera shutters clicked and some bulbs flashed. I did my duty and lit one of the wicks. Then I went back to the same corner where I hid the night before and hoped I would be forgotten.

Kiran is great with children. Intuitively, she spent most of her time focusing on the youngsters from this Himachal hill town who have most likely never been to Rajasthan. It is likely that Kiran’s paintings are the closest some of them will ever get to India’s most iconic state. The little ones followed her around as she explained the meaning of and techniques behind some of her work. The children were genuinely paying attention to her until the irresistible came between the children and the art. In the middle of an explanation, one child observed the nearby restaurant’s delivery of trays of sweets. He took off like a shot through the crowd, his head at about waist level with most of the guests. He filled his mouth with the packaged treats. Then another, followed by three. In the matter of ten seconds, Kiran’s loyal following of attentive, budding artists had dissipated from twenty or so to perhaps two. When she had finished her sentence, even she realized that when competing with candy, her art does not stand a chance with children.

A cultural program followed the ceremony at an outdoor theater above the gallery in Kiran’s honor. The setting and weather compensated for some of the tiring performances and painfully long and pointless speeches. The sun shone intensely; only puffy cotton ball clouds got in the way. A breeze from the mountains kept the heat from becoming too powerful. Among the imposing perfumed pines of Himachal on this splendid day for all, not even some of the most amateurish acts and tiring local musical renditions on percussions and strings could ruin it. I fought through the squeaky repetitious snake charmer music of boys whose future in the performing arts is shaky at best. At the same time, it is what the personnel at the Trust want to see take place: art, music, and expression in an environment where children are encouraged. It is therefore easy to overlook the inadequacies of these beginners and still encourage them to create.

A cute musician in residence from Russia played several instruments brilliantly and sang in a few languages including her own. This delighted many from her homeland who make it a point to come to the Trust, whose founder was also from Russia. She claims to play over sixty instruments, some I have never heard of because they are non-traditional to modern music. After hearing the polyglot perform on something resembling a saxophone and other stringed gadgets, I was convinced she could brilliantly play a piece by Liszt with only a blade of grass in her mouth. The tall and multi-talented AJ brought over a plastic blue chair and joined me in the shade near a powerful amplifier. He leaned over to gain my ear.

“She’s rather good. Do you play any instruments?”

“Do my mp3 player and stereo count? If I had tried out for my high school band as the triangle player, I would have been placed on the reserve team.” That last comment sent him laughing; the two front legs of his plastic chair came up and nearly toppled him over on his back.

Not just because I have lived in his country, but AJ and I got along from the get go. He gets the American sense of humor without my having to offer any follow up. He and his wife see India the same way as I do. They are admittedly outsiders, though they want to grasp India below the surface. We share the same fascination, madness, and confusion towards India. With strong hopes to live here on a full-time basis, they keep an apartment in Delhi while they travel the country in search of prospects. AJ and Anja often find it impossible to reconcile the cultural conflicts between what they see in India on a daily basis and their own upbringing. While indignant as I am at the gross social injustices they have observed, they are not so simple-minded to think they can change any of it. Nevertheless, the couple maintains a firm belief that, as professionals in the Dutch public services sector, some things can be done accomplished. They neither curse nor embrace India. Rather, they accept it for what it is and do their part to bring about small change where so much is immediately needed. They work through the obvious and appreciate the nation’s ability to function with grace amid the chaos.

AJ told me a story about an apple grower from Himachal that sums up his feelings towards the backward (my words, not his) attitudes of many who have yet to let go some of their customs. Some are so illogically applied that a Westerner would be aghast at the horrific consequences.

There was this farmer in Himachal Pradesh, a region with a bountiful apple crop. He heard about the high prices for apples in Delhi, so he arranged and accompanied a shipment there and his efforts were rather profitable. He became more aware of the domestic market by connecting with others in the same business.

AJ picked it up from there. “He heard the prices in Goa were even higher so he shipped a lot to Goa.”

“And he went along with the shipment?”

“Yes, he went along to sell the apples. And then he got to a hotel, and he wanted to have dinner there. And he ordered meat. Originally, he thought it would be chicken.” In Himachal Pradesh, the word meat is synonymous with chicken. There are no other options, but for perhaps mutton.

“So this guy, a Hindu, had accidentally eaten beef.” I summed up. Among Christians in Goa, beef is perfectly acceptable and common. But for an uneducated farmer from the north, he was totally unaware.

“Yes, he didn’t know. He threw up, and he was very sorry. He felt very guilty and he didn’t know what to do. He left for his village the very next day. When he got back home, he called a meeting of the village leaders out of guilt. The villagers held a collection for him.

“And with this collection, they built a house outside the village where he could live…without his wife and children.”

“But his wife and children”, I wanted to confirm, “weren’t permitted to go with him.”

“No. And he wouldn’t let them. That would put a spell on them. This is what I found the hardest part about this, or the most interesting part, or whatever way you want to define it, of course. People have been kicked out of their communities probably for the better part of history. But this was a strange mixture of what he wanted for himself and what the community wanted. He didn’t object to it.” The man’s honesty and deep guilt earned him a sentence of banishment from his peers.

“He never resisted?”

“No. It is very Calvinistic, very Christian actually, to suffer for your mistakes.”

As far as the village was concerned, they were being understanding and compassionate.

“When he left the village and went to his house, it was a crowd of mourning people.”

“As he left the village.”

AJ nodded. “As he left the village. He went to his house like a goodbye party or something.” The farmer’s family was permitted to pay him occasional visits, but they did not go with him. As far as AJ understands, the farmer has never been invited back into the community and continues to this day to endure a punishment for a harmless accident of which he was unaware at the time.

Kiran Soni’s art focuses a great deal on rural Rajasthan and the plight of the state’s women, an approach totally in line with her activist tendencies as a government official. But Kiran the artist is but one side of the multifaceted woman, the one aspect that is surprising to most others does little to interest me. It might have much to do with my indifference to art as a whole. I cannot say.

Her art is what you make of it. I have had the great fortune of knowing the woman far more than the artist. She is a lady whose unconditional generosity and kindness to me far outclasses any oil portrait or watercolor landscape. I know the woman who not only invites me as a stranger into her home, but asks me to join her in her quarters late at night aside her husband. She has her nightwear on and her hair is wrapped up, encased in a plastic cover for tomorrow. I know the elegant woman who does not take any particular excitement in the sound of her own voice; she communicates more effectively by listening than by speaking. Though she wields much political power over the lives of others, I know the woman who sits on her bed at night and flips through a trashy, glossy woman’s magazine. I converse with her and write about her without fear of reproach or being asked to leave. I question her, critique her, and call her out on issues when I think she has erred in her arguments. And still she and her husband remain the key figures to the success of my time in India. The woman’s art may earn her tacit publicity and adulation. But as a whole, the artist is a mere fraction of the woman.

Advertisement

Tot: 0.201s; Tpl: 0.016s; cc: 22; qc: 110; dbt: 0.1374s; 1; m:domysql w:travelblog (10.17.0.13); sld: 1;

; mem: 1.5mb