Advertisement

Published: March 15th 2009

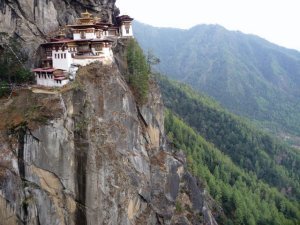

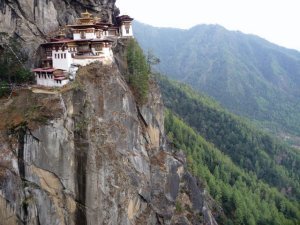

silencing view

silencing view

Tatkshang Goemba, held onto the mountain by the hair of angelsImagine a Switzerland cut off from the rest of the world until very recently, where internet and television have been permitted only in the last ten years, where 19 languages are spoken by a population smaller than that of Glasgow, where more than 600 species of orchid and more than 50 species of rhododendron grow, where the monarch’s crown features a bird not jewels, and where Buddhism suffuses each facet of everyday life. A country so mountainous that the only way to get from east to west was, until recently, to cross the border into the neighbouring country. Where one of its nature reserves was created to protect the habitat of the yeti. A country that stands precariously between two of the world’s emerging superpowers, having watched one or other of them absorb many of its neighbours. A country where the reigning monarch abdicated in favour of his Oxford-educated son in order to facilitate the country’s transition to democracy, ever mindful of the chaos this process has caused in nearby Nepal.

Meet Bhutan, a country braving struggling with the competing tensions of modernisation and tradition, and my destination for ten days at the end of February.

There are several

myths about travelling to Bhutan: that the number of tourist visas are limited, that you cannot travel except in a group, that it is prohibitively expensive. In fact, it isn’t as expensive as all that. Yes, there is a tourism “royalty” of US$200 per person per day (unless you are own your own, in which case there is a slight surcharge), but this covers all board and accommodation (although the top-end hotels will charge extra), as well as your guide, driver, vehicle and fuel. It would be possible to get through the trip without spending a cent more. The one “myth” that is true is that entirely solo travel - i.e., without a guide - is not permitted.

Bhutan wasn’t particularly “on my list” - I too would have said I believed some of the misinformation about travelling in the country, had I stopped to think about it - but then there are very few places I won’t consider, given the right opportunity and/or company. So, when Nancy, an erstwhile elephant project volunteer with a fellow passion for wilderness and places off-the-beaten-track, emailed me in late August about a trip a friend of hers was organising to Bhutan and

invited me to join her, I stopped for about three-and-a-half seconds before responding with an emphatic “I would LOVE to go!!!”. A month or so later, a London-based friend asked me what my next travel plans were, and I was justifiably teased for responding, albeit unintentionally pompously, “Well, the only thing in the diary is Bhutan at the end of February next year…”

The next few months trundled by in a haze of Africa and elephants. Bhutan was in the diary; it wasn’t going anywhere, I could get on with other things in the meantime. I came home to snow in January, unpacked Africa and re-packed for seven weeks in Asia, almost without thinking about it. Bangkok warmed me up again, and I had a blast there for a week, living on a day-by-day basis, working out what sights and sounds to absorb next. Suddenly, before I was really ready for it, and certainly before I’d finished doing my homework, I was in a taxi on the way to the Bangkok airport hotel where we were meeting the day before our crack-of-dawn flight to Paro in Bhutan. I dusted off my Lonely Planet, feeling like a naughty kid who

hadn’t done her prep and who was about to be caught out.

The trip was really a kind of dry run. Jeff has had a long-time love affair with Bhutan and has kept in touch with the guide from his first trip, the delightful, gentle and highly knowledgeable Tshetem. Together, they are exploring the options for co-ordinating trips to this part of the world, including, possibly, to Sikkim, Assam, Darjeeling and/or Ladakh, but this was the first with Jeff’s involvement, and he’d essentially roped in friends as guinea pigs. I was the wild card, only vetted second-hand, as it were, through Nancy. It was a small group - only five of us, and Jeff, Tshetem and our loveable teddy-bear of a driver, Dorje - but we all got on superbly.

I’ve just taken a break from writing to make a first pass at sorting through which photographs to upload with this blog… and have narrowed the selection down to 105. While I fear that this may test the patience of even my kindest friends, for me, it is indicative of the extent to which Bhutan really is different from the rest of the world in every way.

Architecturally, the traditional design of Bhutan’s houses, which is now being delightfully reflected and updated in Thimphu’s apartment blocks, might have distant, curious and illogical echoes of Swiss chalets, but there is nothing Swiss about the imposing dzongs, the former fortresses which then, as now, combine the central administrative and religious functions for their dzongkhag (district). This combination of purposes is just one of the many ways in which Buddhism IS life in Bhutan. There really is no “religion” here in any kind of separate, pigeonhole-able sense that we might view it in the West; instead Buddhism, in all its manifestations and variations, suffuses every aspect of life, past, present and future. Walking through the forests and up and down the country’s mountains, you trip over a richness of prayer flags, chortens (stupas) and chukor mani, the Bhutanese prayer-wheels driven by the mountain streams over which they are built, so as to ensure that the prayers fly heavenwards for so long as there is water coming down the mountains. You do not name your own child. S/he is taken to the temple at a few days of age, and the lama draws names out on straws - the gods decide.

steep descent

steep descent

the last stage of the ascent to Tiger's Nest paradoxically begins with a dizzying descentBefore supping the local hooch, arra, you must flick some droplets around you to appease the spirits. The farmhouse where we stayed our last night might have look a little rundown, but its fabulous choesham (shrine room) belied the owners’ wealth. Outside my window that night, I noticed a scruffy kind of mobile made of leaves and twigs and hair pinned to the outside of the window-frame. It is a trap for the evil spirits that the owners must fear lurk around here. Many of the dogs are not owned by anyone in Bhutan, yet they look well fed. They are. Their night-time barking is indulged, if not encouraged, because it wards off evil spirits. During the day-time, the dogs sleep off the night’s exertions in whichever patch of sunlight they favour, and people walk around them.

Buddhism and history interweave to what seems a confusing degree, until you learn simply to accept the result. The Zhabdrung Ngawang Namgyal, arguably Bhutan’s most famous “historical” character, celebrated in the Punakha Domchoe for his defeat of the Tibetans in 1639 and instrumental in designing many aspects of Bhutan’s culture and traditions, creating a code of law and codifying religious teachings, appears

nearly there

nearly there

two-thirds of the way up to the Tiger's Nestas part of the triumvirate of figures in the altar of Punakha Dzong’s assembly hall. He is at the Buddha’s left hand, while the Guru Rinpoche is at the Buddha’s left. Now the latter, arriving in Bhutan in the eighth century on the back of a flying tiger to defeat demons, might more readily be characterised as a mythical/quasi-religious figure in our simplistic Western terms, and the Zhabdrung as a very “real” person in Bhutan’s political past, yet both are treated as “religious” figures here.

From the moment I stepped off the plane - in fact, from the moment we flew into Bhutan’s airspace - I was enchanted. Villages and farms seem to hover on mountain tops as if only accessible from the sky. Improbable tracks hairpin up hillsides carved, centuries back, wherever remotely possible, into steps to maximise the amount of land for cultivation. These steps may only be a yard or two wide, each boxed in neatly with a low mud wall, yet that is a little more land made available for growing rice and potatoes and barley. Even the airport itself is delightful, its main building a multi-storey version of the traditional house. The more I

saw of Bhutan, the more I was amazed that they managed to find enough flat (or flatten-able) ground to construct a runway; the Paro valley is certainly the only place this appears to be possible, even if it is then an hour or so’s drive to the present-day capital, Thimphu. In fact, the number of aircraft that can land here - given the brevity of the runway and its altitude - is extremely limited, and flights are often cancelled or re-routed if visibility is affected because it is a VFR (visual flight rules)-only runway. The road that runs parallel to the runway is reputed - and I readily believe this - to be the longest stretch of straight road in Bhutan, and therefore a challenge for drivers more accustomed to turning the wheel every few seconds as they negotiate mountain passes.

Only a few minutes out of the airport and I meet my first Bhutanese dzong, the imposing Paro Dzong that dominates two valleys at their conjoining. We cross the river at the Dzong’s cantilever bridge, Nyamai Zam, which is of traditional Bhutanese design, a covered bridge with a tower at each end. Once over this and up the

hill to the dzong’s single entrance, you still cannot walk straight into its first dochey (courtyard): once through the imposing entrance, you turn into a passage that then does a second right-angled turn, reminding you once again that these were originally fortifications needing to withstand attack. For the most part, dzongs have two docheys, one lined with local government/administrative buildings (including the law courts, I was pleased to see - even if, just from the outside, these were just a little bit different from the good old Royal Courts of Justice in the Strand) and one with monastic buildings. “Monk-school” was just out when we arrived, and young monks in their fabulous burgundy robes were relaxing after the exigencies of the day’s tuition. All of the buildings, no matter their purpose, were similarly decorated, with woodwork and beam-ends painted colourfully if stylistically. Inside the main lhakhang (temple), the walls were covered with silk hangings in an attempt to protect their fabulous seventeenth century murals. Tshetem showed us round, lifting each hanging in turn and I had my introduction to Bhutan’s Buddhism. Just when I think I have understood one facet of Buddhism somewhere in south/south-east/east Asia, something else comes up,

and this was no exception. Now I was meeting Tantric Buddhism with its arguable origins in the shamanistic, ancient religion, Bon, and meeting new figures such as the Guru Rinpoche. Confused? I decided that I will simply have to enjoy the fact that here is something that, to a lay outsider, cannot be understood in a nice, compartmented fashion - here, Nepalese Hindu-Buddhism; there, Mongolia’s re-created quasi-Tibetan Buddhism; over there again, China’s Taoist-Buddhism - however frustrating that is to my organised, legalistic mind. It just is.

But one common factor emerges time and again: the amount of time, effort and resource that goes into celebrating (or appeasing) the gods and spirits, whatever the name of the “religion” in which this is done. The next day we hiked up to Taktshang Goemba, better known, perhaps, as Tiger’s Nest. 900m above our starting point in Paro valley, here is an extraordinary construction apparently glued partway up an imposing cliff-face. To the uninitiated, there seems no reason for building it “just there”, unless it is to try and defy the law of gravity. You cannot even get to the neighbouring building, “just round the corner” without climbing to the top of the

mountain and descending on a different side. Yet here, veritably, is a building that is held on, as they say, with the hair of angels. For only the second time in recent memory, a view took my breath away. I was speechless, silenced at man’s ingenuity and creativity. Although the Goemba had flirted with us, blinking at us from between the trees, as we hiked through the forest, and we had been able admire it from the teahouse across the valley partway up, it was only when we emerged at the lookout point on the second-to-last leg of the climb, a lookout point that is actually higher than the Goemba, that I was truly amazed. Here it seems as if you can reach out and touch it, yet you have 400+ steps to descend and ascend as you round the final corner of the valley’s edge to get there. I found it hard to concentrate on the precipitous descent. At every corner, I was dazzled by the building’s magnificence and improbability. In vain did I try and resolve not to photograph it at each and every turn. Inside, we met the resident lama - what a place to live! -

who took us into the main temple and then down to the cave where the Guru Rinpoche is said to have meditated before taking on the demons. Even for an avowed atheist, this was an extraordinarily moving experience. Everywhere we looked, there was a richness of decoration, whether in the murals (including, a little too graphically for my taste, an illustration of the defeat of the female demon), the altars or the embroidered brocade. Ahead of us were a group from eastern Bhutan. Making a pilgrimage here is considered high on the merit-acquiring scale for Bhutanese Buddhists. I had had some sweet chatter with them as we all made the final descent and ascent, yet I felt almost envious of their fulfilment here, and guilty of intruding on their special moment as we all crowded into the antechamber before the Guru’s cave. On the way back down, I went ahead. I was simply too moved by the day. I wanted time on my own, bouncing downhill through the trees, trying to absorb a little of what I had learnt and seen.

It was all a little different the next day. En route to Phobjikha Valley, one of the places

snow lions

snow lions

beam detail at Gangte Goembawhere the rare black-necked cranes spend the winter having flown over the Himalaya from Tibet, and the kicking-off point for our three-day trek two days’ later, it snowed. We’d been threatened with snow in Thimphu, but, fortunately, we were blessed with a crisp sunny day instead, although it was still distinctly cold. Here, we’d just passed through the snow-line - I’d noticed tiny “puddles” of unmelted snow from my vantage point in the front seat of the car, when it actually started to snow. It had been a long drive, and daylight was failing by the time we reached our destination, yet the flakes were still coming down. It all looked very pretty by the light of the guesthouse, but was there a Plan B for the trek? Call me a wimp (and I am), but I really didn’t fancy trekking in snow, at least not in the kit I’d brought with me… And what about camping in the snow???

Two days’ later, you could barely tell it had snowed. In the meantime, the snow had actually assisted us in spotting the black-necked cranes, fabulous birds that stand more than five feet high, and that could equally well have

been called red-crowned or black-tailed cranes - just pick a feature. It had also made our trip to the Gangte Goemba, a huge local monastic complex, particularly scenic, and had answered the question of what Bhutanese kids do in the snow. No, not build snowmen, but build snow chortens… oh, and, of course, have a snowball fight. As do the younger monks, a rare insight into their humanity, notwithstanding the maroon robes. We set off on our trek, the only effects of the recent snow the amount of mud underfoot and the still-chill temperatures.

The trek was an extraordinary privilege. This was no tourist trail with signposts and marked campsites. This was a step into Bhutanese rural people’s everyday life, these narrow tracks through the forests, and up and down mountains. Miles, sometimes days’, from the nearest road or surface wide enough for any kind of wheeled traffic, these were tracks that the Bhutanese had walked, with their yaks, ponies, cows, mules, for centuries, as they move between villages, and between winter and summer pastures, and which they still walk today. The forests were awe-inspiring in the height of the hemlocks, spruces and cypress; in the variety of the

Phobjikha valley village

Phobjikha valley village

the last human habitation we would see for 24 hoursplant-life, orchids, rhododendrons, gorgeous mauve primroses and all; and in the intensity of their growth, whether deciduous, evergreen or bamboo. Wildlife was never far away, though reluctant to be seen. We came across a recent scent-scrape of a clouded leopard, and scat of both fox and common leopard. Towards the end of the trek we were rewarded with a good view of a palm civet as it lolloped across the rocks, and the entertaining sight of a troop of grey langurs playing in the treetops. The unlikely-sounding cries of barking deer (mustjac) had accompanied our departure the last morning. Birds flitted overhead from time to time, the colourful “his” and “hers” of the minivets (he’s red-breasted, she’s yellow-breasted), and the gorgeous blue-throated barbets, another bird that could have been named after various distinctive parts of its glorious plumage, to name but a few. No further sign of the big guys - we’d had a wonderful sighting of Himalayan griffin at Gangte Goemba - though a couple of rufous-necked hornbills flew over at one point.

But the star of the trek was not the countryside, not human and not wild, but semi-domesticated and unintended: Dog, pronounced “Doe-gee” in our attempt

to Dzongkha-ify his name in line with the most common language spoken in this part of Bhutan. Dog adopted us from very early on, in fact from before we left for the trek. He first came to our attention when we were watching the horsemen prepare the sturdy steeds who were to carry our belongings and camping equipment. Nothing unusual, a dog in such situations, but this one was having a great old time, tossing around a piece of material and catching it again. “That looks like a glove,” I remarked out loud, to no-one in particular. Nancy caught up with us a few minutes later. “You’ll never believe,” she confessed to me, “I’ve dropped one of my gloves.”

We set off ahead of the horsemen, and Dog accompanied us, tail waving high. At first, it was a bit of a game. He’d canter off into the fields on either side of us, checking up on the cows or whatever had taken his fancy, and we’d either find him waiting for us ahead on the track or hear him running up behind to catch up. If we stopped for too long to look at a view or a bird

or an anything, he’d start whimpering. “Come on guys, we’ve got places to be!” The first afternoon, he left us, and we didn’t know if he’d gone back or gone on ahead with the camp assistants who’d done their morning duty of carrying and dishing out our lunch, and had gone off to catch up with the horsemen (who had overtaken us mid-morning) and set up camp. But there he was, lying on a small rise in the ground, keeping an eye on proceedings, and we had a rapturous welcome. The horsemen were also delighted to have Dog along. The risk of leopard taking one of the ponies at night was very real and they were intending to sleep out with their animals, so Dog’s ears were a vital addition.

The next day he walked with us all day. Yes, his presence might have prevented us from seeing something or other, but this was more than compensated by the fun and entertainment he provided. He’d trot off ahead but, if he reached a division in the path, he’d walk on a few steps, and then turn round as if to check he’d made the right decision. Late in the

a chukor mani

a chukor mani

24/7 prayer submissionmorning, he started hanging back and lying without obvious reason. Nicholas astutely diagnosed thirst so both he and I took turns pouring water from our bottles onto our cupped hands, which Dog lapped up vigorously. He took such an interest in the source of the water, it was all we could do to prevent him seizing and upending the water-bottles himself. On more than one occasion after that, we had a Dog-stop, gently suggesting to Dog that he might like to refresh himself in the stream we were passing. However, he never looked quite as interested in stream water as he did from the hand-held version. High Maintenance Canine, Dog was becoming.

The third day was the Day Of The Suspension Bridge. Dog did not like suspension bridges, probably because of the nasty way they swayed. He balked at the first one, taking us so much by surprise that Nicholas didn’t really think twice about picking him up and carrying him over, and, for a semi-feral dog, Dog was extremely docile in his arms. However, by the second bridge, the boys had decided Dog needed to become a Man. Anna and I crossed first, leaving the boys to work

out how this was going to be achieved. Certainly, persuasion wasn’t going to work. Dog wasn’t having any of it, and remained steadfastly on the nice firm ground at the end of the bridge, notwithstanding the verbal encouragement from the three male humans twenty feet away from him. Tshetem broke first, and went back to carry Dog the first few yards onto the bridge. I didn’t think dogs could crawl on their hands and knees, but Dog did, keeping his body low as he headed cautiously back for the safety of the stationary land. Take two. This time, Tshetem carried him much further onto the bridge, and he and Jeff crowded the bridge behind Dog, forcing him to walk forwards. After several painful minutes and lots of encouragement from Nicholas, Anna and myself, Dog finally reached us to a banner-waving welcome. As soon as he set foot on terra firma, though, he was off again, tail held high, as if to ask what all the fuss was about. But the third bridge was the longest. At the far side we could see Nancy and Dorje waiting for us. There was no point going to extremes to get Dog across this

one; he would just have to come back across fairly shortly as we hoped he’d join the horsemen in walking back to Phobjikha Valley. We bade him a fond farewell and, one by one, crossed the bridge ourselves. But Dog was going crazy behind us. He still refused to step foot onto the bridge, and dashed down to the river-side to see if there was another way of crossing there. I was terrified he would try to swim the river. This was the Punak Tsang Chhu, a glacial comparative-torrent, and Dog would have been killed if he’d tried. I urged the others to get out of Dog’s sight in the hope he’d settle down, and we went over to chew the fat with the stay-behinds, and to enjoy a well-earned beer and snacks. Some time later, however, something caught the corner of my eye and I looked up. There was Dog, only a few yards from our end of the bridge. Yes, he had conquered his fears and made it across the bridge - which was no doubt far more stable without those heavy humans on it. We were so proud of him! He was cosseted and indulged, and broke

Dog in charge

Dog in charge

the first evening's campsite in the forestour hearts all over again. Both Anna and I, independently, had spent some hours on the trek trying to work out whether it was at all possible to take him home with us…

Advertisement

Tot: 0.105s; Tpl: 0.03s; cc: 12; qc: 28; dbt: 0.0487s; 1; m:domysql w:travelblog (10.17.0.13); sld: 1;

; mem: 1.3mb

Lynn

non-member comment

What an adventure!

This is fantastic. Great job of bringing to us something that most people will never experience. Aren't you the lucky one! But one burning question - what happened to Dog (my new hero)?