Advertisement

Published: September 1st 2007

Yesterday... Today

Yesterday... Today

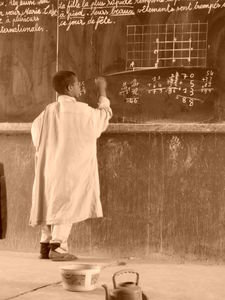

Photo: Amelie MouchetteI got my first taste of Mali in Banjul, Gambia, while trying to localize the relevant consulate. This had turned out to be a decaying shack from whose balcony hung the remaining shreds of what must have been once a flag. Inside the courtyard, written in chalk on the wall, there were a name, a phone number and the invitation to call. Had I been elsewhere I wouldn’t have given credit to what I was actually seeing, but in Africa, I’ve learnt it by now, impossible is nothing. So I just found a phone booth and called and -most surreal of all- the consul of Mali himself, Mr.Hariri, actually answered and explained me that the Banjul consulate had been closed and that therefore I would have to get to the one in Dakar to arrange for my visa. And with such a start I was sure I wasn’t heading for the most organized of the Countries. Even by african standards.

At the border, the border guard on duty tried to extort a

premium on my visa (I had finally decided not to return to Dakar for it and instead try my luck directly at the border) but they gave up

as soon as the rumour that I was

intimate with Mr.Hariri reached them. Rumour spread by myself, admittedly. So I reached Kayes, my first stop in the Country. The temperature was unbearable and the recent rains had further intensified both heat and stench. I lodged at

Maison de la jeunesse, your typical african hotel where the idea of ordinary maintenance (ig whitewashing) seems to die the very same inauguration day. The shared toilet smelled so much to make me think that someone had died there several days before and they were waiting for the arrival of the coroner to remove the corpse.

Even in Kayes, not at all a touristy city, you get your first morsel of what seems to be Malian endemic disease: the

guidism. That peculiar tendency to think that every foreigner is a dumm who will finally yield to the many perils of the unknown if not accompanied by a wise and competent local guide. The virus is so widespread that the government, in a flebile attempt to circumscribe it, releases a card that certifies that a certain person really is a guide. But, if in theory such a measure could have been effective, in reality

turned out to be a sort of boomerang, inasmuch as now the bearers of such certificate consider the possession of it as a divine right to make visitors life miserable.

Kayes is linked to Bamako by a railway line dating back to French colonial times, it covers the 600 Km distance in 24 hours. A remarkable average of 25 Km/h! And in Bamako, metropolis similar to Dakar but with more trees and less car,

guidism gets more intense. Lodged at the excellent

Mission Catholique, you have the problem, every single time you leave or arrive, to deal with a nourished group of

cool-man-don' t-worry-be-happy guides. If ignored, they pull out the damned yellow card and just flicker it in your face. There is no way to get rid of them. At the beginning, I thought this obsession for being your guide was just plain calculation, but after dealing (unavoidablly) with a good number of them, I begun to suspect that many are genuinely convinced of what they say. Of the impossibility of travelling around Mali without a guide.

Things degenerate when approaching the Dogon Country, true heart of Malian tourist industry. In Segou or Mopti, just to name

two of them, there is no way of taking a walk undisturbed: a guide and his card are always there for you. All of them offer pretty much the same tour and price depends in wide measure from where you come from. And just two nationalities seem to exist in Malian popular imagination: 1) the French (or European, terms used almost as synonyms) who are white, rich and speak french; 2) the Americans who are also white, even richer then the French and speak English. Belonging to the second category usually means higher prices.

On the Kayes-Bamako train I had met Roberto, a Swiss-Italian in sabbatical year, and together we travelled to the Dogon Country. At every intermediate stage, in response to the unavoidable harassment from the usual wanna-be-guide, Roberto made a point of honor in explaining that we were travellers, not tourists. A quiete obscure diference at the eyes of locals and, to be sincere, a rather feeble one at my eyes too. In reality, true travellers died many years ago, the very moment the idea of tourism was born. And a XXI century round-the-world journey is closer to an Ibiza sunworshipping summer rather than to the Marco

Polo experience. So, Yes, we are tourists, but poor ones. And poor tourists do not hire guides.

We had managed to skip almost all the attacks, to skillfully reject the continuous

advices not to venture alone in that valley of restlessness and mystery. Among the dozens of absurd stories told to us, the one I liked best was Adil’s from Mopti. According to him, Mali law states that is mandatory for any foreigner entering Dogon Country to engage a guide. Offenders will be stopped by the police at Bandiagara check-point (which in reality doesn’t exist) and escorted to the nearest tourism office where some kind of

state guide would be assigned to the unprovided tourist. All this, obvious, at his own expenses. Moreover, in such a case the tourist can not bargain on the price! I confess: I laughed in his face. I know, it isn’t nice, but the idea of this Perry Mason of the guides coercively assigned to us by the Malian authorities was indeed too surreal for me to keep a straight face. Nevertheless, once in Bandiagara, last stop before the real Dogon villages, we had met Bah, apparently one of the very few guides not

belonging to the

cool-man-don' t-worry-be-happy kind, a laconic french speaking fella of little economic pretensions. And we ended up hiring him.

Following Bah, we trekked during four days starting from Dourou and finally arriving at Kani Kombolé, walking southbound along the falaise. 25 Km covered at an average not less shameful than the one kept a few days before on the train: 6 Km/day! Our typical day would invariably start at dawn (unavoidable inasmuch as we were sleeping under the stars), then breakfast, a visit to the village where we had spent the night, a mere hour of walk to reach next village, maxi-mega lunch break from 10am to 5pm and finally another short stroll before the definitive evening stop to camp. After three days of such bromide routine, I told Bah that a venerable 80 years old man on wheelchair would have covered a greater distance than ourselves.

But, if on the sportive side the Dogon Country trekking turned out to be null, on the cultural one has been one of the most interesting experience I’ve had to date. Every village differs from the others in architecture, customs and, in some cases, in religious creeds too. Even

Tuaregs

Tuaregs

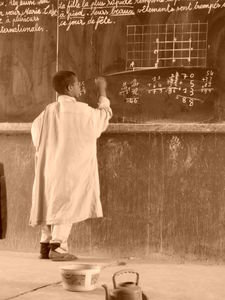

Photo: Amelie Mouchettemore surprising is perhaps the high level of social-economic autonomy they enjoy. They are almost self-sufficient thanks to millet, onion, mango and other crops and to the breeding of goats, chickens and cattle and, up to few years ago, they kept a sort of autonomy also on the juridical plan, with a local council where the elders from the village were in charge of solving all litigations between community members. Today, unfortunately, are more and more those who decide to appeal to lawyers and judges of European breed ignoring the self-taught (and uninterested) wisdom of their own old ones.

In the

minus column, instead, I’ve been struck by the exasperated tendency to beg. Children know only one phrase in French: “Donnez moi l’argent!“ (

Give me the money). Adults don’t even know that, but their hands open to money as swiftly as their minds close to new ideas. In the village of Yaba Tulun, as an example, we went to visit the

hogon, the spiritual leader of the village only to be received with these words: “Donnez moi les kola“. From him, a spiritual leader, a wise man. Depressing.

But our guide was second to no one when it came to wisdom. After realizing that Roberto lives in Bern, same city of one of his

fiancèes, he asked me if I had ever been to Switzerland. When I answered that I hadn’t, he replied with all the seriousness of a federal guide: “You should go. You know, in Switzerland they have TV in every house“. Amen.

ITALIANO La versione italiana di questo blog la trovi sul sito Vagabondo.net

Link:

Avvistami, Salutami, Assillami, Guidami

Advertisement

Tot: 0.373s; Tpl: 0.013s; cc: 37; qc: 156; dbt: 0.2097s; 1; m:domysql w:travelblog (10.17.0.13); sld: 1;

; mem: 1.5mb

Kate Hildebrand

Kate Hildebrand

hi Marco

this was a great read! I can't wait to get to Africa someday ^__^