Advertisement

Published: July 24th 2008

Medan: English Lesson with a Happy Ending

It’s a day faster and with Air Asia it’s actually cheaper to fly KL to Medan, Indonesia's third largest city, a quick hop across the Straights of Malaka but I need to reach it by sea, want to relive bygone days of explorers and spice traders. The ship, however, is oblivious to any romantic notions, a low aluminium hull tosses its cargo from port to starboard and back mile after nautical mile, air con preserving passengers like produce in a refrigerator, no promenade deck for shuffleboard, just a muddy window pane, and a neighbour reeking of tobacco smoke and in dire need of a shower. Customs and Immigration are efficient and friendly, a young man in a tight grey uniform reminiscent of C.H.I.P.S. steers me to the front of the line and to a small glassed in room where within seconds a one month visa is stamped inside my passport. I present myself to the Immigration Officer who welcomes me with a smile, “Hello Sir, how are you?” he asks. “Uuuuh,” I’m dumfounded. When was the last time an officer working the US-Canada P.O.E. used such language? A throng of dark brown faces is

milling about the port’s single exit, sacks of imported goods slung over strong shoulders, young men smoking and calling to arrivals directing them to one of several coaches, and a taxi, ojek, becak, car park. I sit up front near a self-important middle-aged woman who flirts with two young baggage boys, each have let their pubescent whiskers grow wild and appear less like young man than strange fruit. She tips them a little something and argues to me that her luggage ought to have my seat though everybody else’s parcels have been heaped in a pile in the rear of the coach. As we propel through the lively streets of downtown I refer to a map in my guidebook and recognise a few landmarks. Four other foreigners seated in the rear and I are the last to pile out, they eavesdrop on my instructions to the driver to stop in front Hotel Raya, one of several budget options encircling Mesjid Raya, a seemingly magnificent white domed mosque towering above a neighbourhood of internet cafes, bakeries and late night food stalls choked with exhaust fumes. For 8$ I enjoy a king size bed with air-con and cable TV and pass out

the rest of the afternoon despite the roar of traffic. At sunset the call to prayer wails through the small streets, the last touch of golden light slides down the mosque’s walls and leaves the yard of tombstones and weedy silhouettes in a peacock blue darkness. A half dozen boys who’ve spent the late day flying kites low over a suspicious mound of earth in the graveyard, return home. Facing the hotel in a row of scantly light warungs I find a seafood curry dish and linger late sipping an iced tea, watch the cats befriend new customers and the parade of wheeled food stalls pedal by in the blur of headlights. A young man drinking with his girlfriend asks if he may talk with me. I learn that he is an artist, carves wood and stone, pounds metal, blows glass, and offers me a tour of his commissions if I’m still in town come the weekend.

There isn’t much for a tourist in Medan, a palace with an unkempt garden, a peeling façade and a shrinking number of stately decorated rooms open to the public, besides none of which are visible, unequipped with even a single bulb. Poor

families whose laundry and cooking pots dry in the midday sun now inhabit the ground floors. A small quarter survives from the colonial age, colourful three story buildings leer above the dust and exhaust, construction and traffic a permanent fixture of Jalan Pemuda. Parked cars, shops’ aggressive window displays and craters dropping hundreds of feet into the earth’s bowels have reinvented the sidewalk. A narrow hall lined to one side by numerous shelves overflowing with creatures carved of wood or moulded in cheap metallic plastics, to the other a long glass case containing faux jewellery and primitive iconography, leads into a curious antique shop. An older woman dressed in a long robe and jilbab camouflages all but her dark aged face and hands, approaches me, appraises me with quick glances, intuiting what I might be after, and what I am willing to pay. A few paces ahead she directs me further into the shop, retrieving from the shelves strange and colourful figurines, holds before me tools, weapons, art for art’s sake, paperweights and dust collectors, from minority tribes across the archipelago, and, she says, I can get a good discount. From her lifetime of collected loot my eyes skim quickly

the cheap stacks of nicknack rubbish, leading deeper inside the grotto to a series of rooms, its contents all but blocking a hazardous circuit among oriental brikabrak, an old motorbike, two nifty old pedal bikes, dazzling light fixtures, ceramics and dollar store china, large and too large to fathom housing indoors wood carvings of beastly gods and demons. An hour later following several cups of tea and haggling and phone calls to the proprietress’ pregnant daughter, a visit to the ATM and assurances that shipping costs would be minimal, I leave the store with a ninety dollar dent in my wallet and a 4.3 kg package under my arm containing a carefully wrapped stack of Chinese bowls and a sinking suspicion Amelia Erhardt may have wound up here. Throughout Asia’s south-east, from India to Guangzhou, from the Mekong to the Ayerwaddy, whether students or housewives, the locals fetch their lunch from the markets in stacking bowls usually made from tin and secured by a simple handle sometimes wound in wicker. I’d never before seen them in fine ceramic, a cracking grey with dark blue emblazoned dragons. Next I visit the post office, a towering relic of the colonial era, the

far end of Pemuda, where after several queues my box is secured and stamped, signed in triplicate and made to look official. “Sir," I call to the man taking it off the scales, “it’s fragile, you know,” I gesture a falling motion, “… CRASH! How do I write that in Bahasa?” “Don’t worry about it,” he assures me. He has obviously never tried shipping water pipes out of Istanbul. Taking up the old antique dealer’s suggestion I order an icecream at TipTop, decorated like it was over seventy years ago, terra cotta tiles and rattan lounge furniture, a few feet from the haze and congestion, the cool desert and a small coffee are wheeled out on a tray by a smart looking old man in a pressed vanilla uniform.

On the cool and spacious veranda of Palace Maimoon a trio of young college students interview me, tape recorder rolling, the unsuspecting foreign visitor answers their questions, “What do you think of Indonesia’s education system?” “What do you think of Indonesia?” and likewise inquiries that require more than a twelve hour visit, half of that unconscious in a hotel room. Perched nearby a vulture swoops in and introduces himself, Adi,

English lesson

English lesson

Adi & the rich kids next door, Medan's answer to the Von Trapp'san English tutor/ wedding MC, whom I’d soon discover has a strong affinity for Whitney Houston and Mariah Cary love ballads. That should’ve been enough to clue me in. “Can you accompany me to my English class later this evening?” he asks. It’s obvious to locals that foreign tourists really have very little to do in Medan. Adi helps me to the museum tucked a way’s away off the LP map where at twenty to four the museum is closing though not scheduled to until five. We sneak in and ask the guards if we my have a look in just one gallery, the woodcarvings. “No,” Adi translates, “they’ve already turned off the lights.” Yup, never mind I’ve already flown half way around the f***ing world. Across the street we find a seat in a simple restaurant, a woman my age about, bearing a striking resemblance to J. Lo, prepares our cold drinks, carrot-tomato and fresh squeezed lemonade. Adi and I sit for a couple hours chatting up J. Lo, the old maitres and a bookish looking girl at the next table, Adi sings from time to time melodies among his repertoire of African-American Divas and teaches me a few

rumah mandi

rumah mandi

the 'bath' is actually used like a well, water is scooped and poured over one's selfphrases in Bahasa Indonesia. We ride a series of opelets, crowded covered mini trucks, long benches placed either side of the bed, headed away from the city centre’s congestion into the evening suburbs, hovels and stylish bungalows shoulder to shoulder along the crumbling biways. Adi and I walk into the quieter back streets to a dead end block where birds chirrup strange calls I realise will become familiar to me in passing months. The sunlight gathers to the edge of view and slips away. The cicadas are quiet, their rhythms taken up by frogs and crickets. Adi guides me to the back door of an unassuming upper middle class home where I shake hands with mom and dad while his students file into he living-room, a high ceiling parlour with gilded furniture and mouldings on the door frame and window frames, an easel and whiteboard set up in the near corner. Four sisters and one brother ranging in age from fourteen to twenty-three take up positions on the sofas. “What did you do today, Rilla?” I ask of the oldest, in glasses, notebook poised on her lap, before asking each in turn and writing their confused verb tenses on the

board. I learn that each of them has woken early and taken a nap in the afternoon as is routine along with a bath all from the same bath water. I picture in my mind one after another soaking themselves in the mandy, not unlike a tub found at an old Japanese sento but much much cooler. My confusion is a source of laughter as they explain the procedure for a bath in the rumah mandy style, scooping a small bucket of water from the mandy basin and pouring it over oneself. I’m treated to a home cooked meal up the block at Adi’s step parents’ where the college professor lounges in his arm chair on the veranda like an orang utang and chats with his wife and Adi. I watch a frog leap among our flip-flops, puffed up gold fish make faces in an aquarium and koi swim figure eights in a narrow fountain set among orchids and a well groomed lawn. Simple tents stand in the neighbourhood’s vacant lots where young entrepreneurs serve powdered drinks and blended juices. Youths and parents gather at their respective favoured ‘juice bar’, playing cards or playing guitars. How many problems may have

been solved had my hometown shared some a simple attitude to evening recreation. In view of the long commute I invite Adi to crash in my king size bed and enjoy an American action flick. “You want a massage?” he asks, seeing me stretch my tired shoulders. He’s skilled, starting with the neck and trapezeus muscles, deltoids, following my spine, working his strong fingers on my lower back and hips. It’s the first time somebody has offered me a massage. He rubs the tight ticklish knots in my hamstrings and my calves, mentioning the wrongly positioned and proportioned muscle development, a consequence of several sports injuries which a decade of visits to the physical therapist, chiropractor, acupuncturist, reflexologist and aroma therapist have made little improvement. “Flip over.” I can’t see the TV anymore so shut my eyes. His fingers tighten and pull along my arms then snap each finger. Then his hands wrap around my upper thighs, highly sensitive, my eyes pressing shut, mind concentrating on a distant landscape disconnected from its body, but to no use, a contented bulge grows inside my shorts, Adi’s hand rubs closer and closer and graces over. He pulls back the elastic for a

look and laughs. And then I’m given my first ever massage with a happy ending.

Nora & the Orang Utangs

Bukit Lawang lies in the hills less than a hundred clicks north-west but the journey requires just over four hours sweating in the back seat of an opolet, a mysterious half hour stop serenaded by teenage punks jamming on ukuleles, wheezing amid the thick smoke of kretek, traffic queues on the narrow strip of road behind slow wide load cargo trucks transporting palm oil piled in large bunches of red date-like fruits. A persistent guide greets me at the park’s entrance, directs me across the river on a wobbly suspension bridge to the overpriced pick of tour groups before complying with my request to head upriver to the backpacker huts. A newer stronger suspension bridge crosses Sungai Bohorok, below bathe children and young couples in the shallow rapids, to a block of wood hut warungs and restaurants relocated fifty metres further and higher above the current after a flash-flood wiped out the village five years back killing nearly three hundred. A footpath twists up the bank past a few stilt dwellings complete with bamboo furnishings selling local handicrafts and

banana pancakes, remnants of the flood, concrete foundations and half structures hide in the tall grass. Jungle Home-stay, a new addition, appears beyond a garden shed, set back from the path with a cozy wrap around restaurant where a young English couple hellos me. My first glimpse of an orang utang, a large woman wobbles towards me dressed in a thin cotton shroud, the manager, Nora, direct, flirtatious and cheeky, she is soon my best friend, pinching my cheek, telling me I smoke like a girl and look five years older when my thinning hair is wet. Kate and Patty of small town North Wales and I dine before a TV set turned to Hindi music videos, the usual handsome couple, the tall dark and handsome hero flexing, she fair skinned, belly undulating, reappearing in various costumes in numerous locales, but ultimately arriving at some Central European capital where locals gather round spell bound in the piazza and a tram snakes past the background. The guide returns under the cover of darkness and mutters a lower price in my ear. I agree and hand over the fee for a two day one night trek into the jungle. A pretty young

Our Guides with Orang Utang

Our Guides with Orang Utang

Sunny's role was to lure the beast off the trail by using most our banana rationsDutch woman has paid twenty dollars more he whispers a heads up.

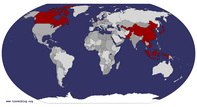

Our expedition, a couple from Amsterdam, she’s a doctor, he’s handsome in a tight pair of shorts and strangely charming stutter, the nineteen year old bombshell from from Eindhoven, Sally, and our guides, a chubby, humoured fellow named Udin, and Sunny, a younger man with a thick mop of hair whose attention is increasingly directed at Sally, and I, dressed in soccer shorts and a thin tank top contrary to the guidebook’s suggestion to cover head to toe against insects and other heathen pestilence, climbs into the hills late morning under an overcast sky and a gentle breeze set at room temperature. Udin points out a grove of rubber trees, the bark scratched in diagonal patterns to let run a thick white sap that collects in half coconut shells placed at the base of each trunk. Along the ridges across the river spread an Australian-financed palm oil plantation, a chainsaw drones far off. A trail leads further into the park toward a strange whooping call, hooouat, hooouat, hooouat, wat, wat, wat, a couple of white handed gibbons, Udin informs us. He answers his mobile. Rangers try to

keep track of primates’ whereabouts and direct guides along numbered paths to spot the animals, warn of danger or keep trekking groups from swarming in one area. The paths twist, bisect, loop, climb, slide through thick jungle, scurry along slopes covered in loose underbrush. We come face to face with a wild male orang utang hanging leisurely a couple metres above us, chewing imaginary food. It’s an experience, our eyes meeting across the evolutionary gap. For the next few hours Udin and Sunny take us scrambling through a snaking network of trails responding to calls on the mobile, leading us to wild and semi-wild orang utangs, the later more dangerous, raised in captivity and apt to grab hold of a trekker’s rucksack in search of ambrosial bananas. We are lucky says our guide, we’ve found a pack of long black tailed Thomas Leaf monkeys with remarkable punk hairdos, long tail macaques and black gibbons. We pause at a crest in the hill to chat with another group, share monkey stories and pass around a couple spliff. Sally buys a few joints she and I will enjoy come evening with a hot cup of black tea, relaxing on the riverbank, refreshed

in the fast current. She and I share stories of the many romantic places we have each travelled to alone. Night falls. A full moon washes the river in a mysterious glow, a sci-fi meets Vietnam war movie set, and jungle sounds close in but for the Dutch couple who’ve yet to discover silence. As though planned each of us wakes with a sore back cringing the thought of a day’s hike but after cleaning up camp Udin and Sunny seem all to accommodating and promise only one hour’s journey on foot. We climb a steep ridge where Sunny is alerted to a familiar rustling in the distance, a blur of amber hair swings gracefully, with surprising speed, covering thirty or more metres in a matter of seconds. “Grab your bags!” warns Udin, “It’s Mina.” She doesn’t appear dangerous, she’s kinda cute in fact. “Back away, come on.” Sunny presents her with a series of bananas slowly tempts her away from the path, Udin instructs us, “Now, go, go!” to climb the ridge. “Did you get a photo?” he asks. Last week Mina befriended a backpacker and sat in his lap for over an hour. That’s a lot of bananas.

The trail climbs back down the ridge and returns us to the river upstream by a deep refreshing pool where our gear is bundled in plastic sacks and tied to a train of oversized innertubes that carry us all too quickly back to the village. Fifty dollars for twenty-seven hours of Sumatran jungle seems steep considering the average Indonesian earns less than a hundred a month but the experience is worth it. And should deforestation eventually wipe out the jungles of Indonesia I’ll have some wonderful stories for the grandkids.

The Karo Highlands

Kay and Patty, the Welsh duo, she fond of her pint, freckled and woven with dreads, he pale, simultaneously innocent and mischievous like a choir boy and hints of a typical British sense of humour, show me the way early morning to the minibus stand, bemos bound for Medan. Chainsmokers pile in and a dozen sealed plastic bags swimming with river fish are stacked in the back seat as we weave through the village. Four hours later the driver ushers my companions and I directly onto a large bus - something out of a Muppets movie - destined for the Karo Highlands. Passengers are crammed in

my attractive charm

my attractive charm

(my skin smells of sweaty cheese is more like)six across on benches that would normally accommodate 1.5 westerners, my how the people are tiny, and how the old wrinkle and shrink smoking their kretak inches from a wide-eyed babe. Cramped and sweating, suffering an irritable stomach and inhaling thick blue streams of smoke, I keep the window open a crack despite instructions to keep it closed. At the first sharp turn in the road, a stream of brown fish juice drips from the roof splatters through the window and covers my left side in stink. I shut the damned window and carry as calm and distant an expression as possible while my contractions arrive closer and closer together until after too many bends in the road we pull into

Berastagi amid a downpour and I lead my friends dashing to the nearest hotel where they enquire about prices and I duck into the toilet and replay jungle noises in reverse.

Berastagi doesn’t look like much at first glance, a city of half a million, an agricultural based economy surrounded by the fertile soil of the Karo Highlands and looming nearby two perfectly conical volcanoes. The main drag cut through town connects big city Medan to the natural

resources, ethnic groups and cool climate of the interior, blink and you’ll miss the Tugu Perjuangan erected on a wide median straddling the drag, between the central produce market and a row of nocturnal warungs, a monument commemorating the Bataks’ resistance against the Dutch in the 1800s and, naturally, fitted with a traditional Batak hipped roofline to resemble a bull’s horns. Curiously, down the block, stands a giant cabbage commemorating perhaps the weapon of choice used against the Dutch. In the rolling hills surrounding town lie dozens of unique wood churches decorated a blend of Lutheran and local influences, simple mosaics of European saints flank doorways, geometric patterns circle the eaves. Surrounded by Muslim peoples including among the most devout of Indonesians, the Acehnese, The Batak were converted to Protestant Christianity in the mid eighteenth century when a German missionary’s sojourn coincided with several years of bumper crops, praise be to Jesus, until which time the Batak were still practising cannibalism on their slain enemies.

Strengthened on antibiotics and two nights’ rest in one, I regain my sense of adventure and hop an opelet for

Dokan, curious to interpret the guide book’s version of “a charming traditional village”, and

bearing in mind the all too familiar and all too disappointing Chinese model with ticket booth, tour groups in bright matching polo shirts and souvenir shops selling factory direct handicrafts. The minivan pulls up to the pumps - recently government subsidies have fallen and the price per litre has rose over a third and all other services have increased in most cases overcompensating - but the pump's nozzle and the van's valve are on opposite sides and a queue is quickly forming. The hose is passed through the van next to a passenger enjoying his kretak - only in Indonesia! I’m let off by a row of fruitstands clustered around a dirt track rolling through farm fields enclosed by palms and tall red flowers. Two young boys leave their friends’ football game in the schoolyard to accompany me to their village. The road forks and continuing right I follow a bluff above a small village surrounded by lush forest, a half dozen horned roofs of sugar palm fibre loom above rusted tin roofs, blue walls, unkempt gardens, and scraggly mutts. The road approaches what appears the finest of the traditional buildings where a young woman peeks her head out the

low door and calls to me, “come in, come in,” waving her hand. I climb the ladder of the stilt house and peer inside letting my eyes adjust to the darkness. A wide walkway of wood planks cuts a central axis, leads past dormant cooking fires and sleeping mats to the back door. The young woman has me sit with her and her cousins and grandmother, a well dressed young couple from Medan sit to the back. Eight families share the dwelling, a cooking fire shared between two, a vast attic for storage space and to hold the smoke which deters mosquitoes. After a wander through the village I sit sketching and draw a crowd of young people, dozens of children, a fraction of them aware of my activity, the majority simply there to play with their friends. The swarm grows restless, teasing, pushing and swaying and soon wrestling.

An opolet fetches me from the roadside just as a downpour begins and lets me off at the bus station in Kabanjahe. In a row of unlight shops I find a restaurant, scratched and dilapidated wood benches and tables stand on an uneven dirt floor, where a half dozen young

Bukit Lawang

Bukit Lawang

can you find four people?women under the charge of an ugly middle aged beast serve me an overpriced chicken bone and avocado juice. A few kilometres north-west lies

Lingga, “the best known and most visited” of the traditional villages, pleasantly small and clustered at the end of a road winding into the back country. Locals gather in the covered market to relax, a few women have cloths laid before them selling onions, garlic, cucumber, potato, chilli, and bags of various spices. Men smoke kretak in the teashops encircling the market. Livelier than Dokan, on the footpaths I encounter folks fetching rice and other supplies from the few sundry shops, tending their cows, chatting with neighbours, playing, smiling. The traditional structures lie in various states of decomposition, fallen planks, torn roofs, rotting floorboards, skeletons of their former selves, carpeted in light green moss, forgotten in the rituals of daily life. A man approaches me, dressed smart and enparting a confident swagger and car salesman smile, instantly recognisable as the tourist liaison come to collect his fee. He directs me past the two finest Karo Batak houses in Lingga, gestures to the nearest and explains it is where the young unmarried men traditionally sleep because during

courtship they cannot stay with their family and the other, he points across the road, is the king’s house, rather small and the interior a dark emptiness. He comments on the wood carving, painting, and the leather weave that binds the slats together, not a single nail is used in the construction. I follow the man inside a small shed where he sits at his desk and pulls out a logbook. Wood carvings hang from strings covering the walls, flutes, pipes, boxes, divining calendars, the handy work of the older men in the village who’ve no longer the energy for and revenue from farm work. He shows the logbook where Germans and French visitors have written their name and address beside an inventory of sold woodcrafts. Honestly they look like cheap junk. I explain that I haven’t the money to spare on crafts but promise to help him instead with a one week itinerary he must organise for a Swiss tour group coming to Sumatra. Exploring the village on my own, disinterested in hearing more lore of bygone traditions, I come upon a small group of children and soon find myself giving an impromptu English lesson to the two eldest

after dinner treat

after dinner treat

jungle ganga rolled with kretek (clove cigarette) and mentholgirls, a mother passes me a thin picture book and we practice animals and bedroom objects vocabulary. Children from the surrounding homes gather and watch and laugh, we play a game of ‘Simon Says’ and sing ‘Head and Shoulders’ while moms arms crossed over their chest watch in disdain as though interviewing me for a job. One grandmother stands among the children, blind and toothless and laughing a soundless joy. I pull out my camera, “Picture time!?” and they scatter with a howling “NOoooo!”

Kay, Patty and I armed with a rough idea of the route follow the road looping behind the guest-house climbing into the backfields. It’s a fresh morning, young students board opelets, folks sitting at teashops call hello. Not a hundred metres of road through Sumatra pass without a friendly hello and a brief inquisition, what’s your name? Country? How old are you? Where you go? The road ascends rolling meadows of rice paddies before a turn-off leads past the ticket booth and trail head, inclines steeply on a narrow strip of asphalt wrapping around the mountain’s base, a long circuitous approach offering an hour later our first glimpse of the peak of

Genung Sibayak. A

wet wall of jungle looms above the road, an occasional motorbike roars past, Kay whinges incessantly about the heat, the humidity, her lack of fitness, always something to which her partner keeps silent. A concrete staircase continues deeper into the foliage approaching the crater, a powerful stench of rotten egg fills the air. A half dozen abandoned campfires lie in small clearings along the path heaped with trash, an increasing number of plastic bottles and food wrappers decorate the trail. Plumes of thick grey smoke spout from cracks coloured yellow among the grey rocky slopes, an interesting photo opp. Hunting along the caldera a descent down the other side towards the hotsprings I inhale too much smoke triggering my irritable bowels. Feeling ill and impatient with our three-headed expedition I bid Kay and Patty happy trails as they pursue the hotsprings and I return along the same route collecting rubbish along the way much to the amusement of local youths trekking mind you with ukuleles and BMX bikes.

Danau Toba

Three bus connections, two long waits, a heavy downpour and six hours later I’m let off at the jetty in Parapat just in time for the last crossing

curious beetle, Genung Sibayak

curious beetle, Genung Sibayak

things you see when doubled over with the trotsto a peninsular paradise on the island of Samosir. Half a dozen westerners and a crowd of locals, many of them long haired touts of the overabundant guest-houses in tourist dead Tuktuk, sit on the topdeck beneath heavy grey clouds painted in watercolours measuring the last light of day. I climbed a volcano on an empty stomach, shat diarrhoea in the bushes on my descent and travelled six hours with cramps, I answer a tout’s question as to why I look unhappy. No worries, he tells me, and from the pier leads me to an affordable guest-house, Liberta’s, the one I’d already highlighted in my guidebook. Unfortunately the only room available is a characterless shed next to the Ping-Pong table/ laundry facilities but assures the manager, Mr Moon, several guests shall be checking out in the morning.

Daybreak opens a crack in the cloud cover, a trail of stepping stones and tree roots leads through the garden between a series of two floored bungalows to a pond’s edge where a square of pavement offers a moment of tai chi. A fisherman in a low dugout paddles the far side of a swath of voluptuous reeds, propels himself tugging with

his hands along a net the length of the bay. A few homes shelter on a bank hugging flooded rice paddies and lily ponds, a young boy and his mother scoop water to bathe themselves and beyond the low treelined summit of Tuktuk climbs the sun sleepy in a bank of clouds. I check into #1, a bungalow with a loft bed and private porch overlooking the spit of garden reaching into the lake. Five mornings in a row I perfect my kopi order, steaming hot with three spoonfuls condensed susu, sit reading my novel or journaling, while the birds chirrup and guavas fall thump off their branch, chickens squabble and the fisherman combs his net.

Next door I meet my neighbour, a tall Italian with long black curly hair, Andre, a financial analyst with a firm in London who does his week’s work in a disciplined day or two, examining data on his laptop, interrupted occasionally with animated phone calls to friends and family back in Turino, business jargon shared with associates in the UK. At breakfast I’m introduced to a young couple from Provence, David, a cook, with spiky blond dreads and creative ideas for pasta, and

Anne Sophie, dark skinned, soft voiced and rolls her own cigarettes, a strong blend picked up in India and kept sealed in a plastic jar with a French label, a black cat on a green background. The loop of hotels, guest-houses, restaurants, shopfronts displaying woodcarving and batik, a couple galleries, signs advertising bicycle and motorbike for hire, magic mushrooms and laundry service around Tuktuk’s bulbous peninsula offers a pleasant hour’s walk. The weather changes quickly and rarely settles for long, clouds blow in and bunch along the caldera’s three hundred metre high cliffs. Besides a few hours’ bikeride up the coast to Simanindo, a walk to the market in Tomok and short jaunts to the German bakery or a cheap delicious meal, I feel most content planted in the garden at Liberta’s. Kay and Patty appear the next day along with a quiet French couple I mistaken for Germans, a towering Scotsman in short shorts whose hipbones at the end of some gorgeous looking thighs reach half way up my ribcage and whose masculinity is sensually highlighted by a slight feminine charm and a brown haired fuzzy chested stud from New Zealand who fancies himself a ladies’ man and whose

petrol stop, Berastagi

petrol stop, Berastagi

DANGEROUS: pump hose passed through the opolet where a passenger sits smokin' a fagaccent registers with me in a murmur. After an hour sipping Bintang with the English speakers I have enough of Kay’s testosterone and thankful I speak French spend the rest of my stay among the Europeans.

Five young men employed at Liberta’s cook, serve meals nearly all day, tend the garden and see to each guest’s comfort, and an added touch, call each of us by name. I learn Wana’s name who tells me in order to remember, “Wana, like, I wanna be with you.” He is tall and handsome, a fresh haircut, a thin trail of chest hair, a cheeky grin, a voice clear and raspy at the same time which bodes poorly for his singing career but we endure his guitar solo through the evening meal. Come nightfall frogs croak with a loud sudden fart like my mom would share whilst relaxing in front of master piece theatre at the end of a long day and a good meal. A furry white canine named Bongo often visits me on the bungalow’s deck where I read and he looks at me puppy-eyed until I feed him another Marie-Susu biscuit and he sleeps by my feet. His adopted daughter,

a tiny, rambunctious pup named Lucky still chases her tail and each day finds her face covered again in stinking mud from the base of a jackfruit tree. I sit immobilised, enveloped in a tale, Animal’s People, the work of an Indian writer, narrated by a victim of an Amrikan faktri’s poisonous gas leak, a slum dweller of Khaufpir, tells of the usual corrupt local politicians, unscrupulous American lawyers, an untrusted philanthropist/ doctor and her courtship with a local singer / victim of the toxic chemical explosion. Andre and I discuss the all too easy possibility of spending an entire two-month visa here in Tuktuk, perhaps renting a large house on the peninsula, a fully equipped traditional horned roof, surrounded by garden and overlooking the bay behind Liberta’s.

Strange. One of my earliest memories is a dark green wet colour, a shade darker, more opaque than the carpet in my parents’ house. I attached to this a feeling of anxiety, something like the undertoad in The World According to Garp. I’m younger than five, probably five, from a bystander’s vantage point you’d see a wheat blond head of waving hair by a B.C. summer lakeshore or river bank, but

my eyes are under water, trying to think where is the bank, a brown shape I’d slipped off. And someone saves me, my big brother or my father, what would Freud have said. In the back garden a trail leads past my deck, beneath a guava tree where birds teach their offspring to feed, along a raised paved walk straddling a two foot slope to the left to a pond cramped with reeds where frogs mate by night and red headed black and white ducks make odd abrupt cooing quacks, and to the right a rectangular thirty or more feet in length bordered at the nearest and furthest corners by red and green palms shading sprightly shrubs and piles of dredged rotting reeds. A hot sunny morning draws me to the cool lake. With Mr Moon’s permission, armed with a hooked saw, I shimmy into the water, a pool enclosed by slithering stems, six foot long tendrils, a result of chemicals released among the lake’s three year old fish farms and churned about by constant motor traffic. The hired help lounge in the shade puffing strong cigarettes, I’m alone, half lawnmower, half drowning fish, trimming the reeds. I submerge my

head to counterbalance while my arms and legs tug and twirl, sink, rise, grasp hold of and lift, pull to shore and plop in a pile. When my head’s underwater I see the slimy green and small explosions of dirt brown and instances of yellow light, and I wonder which was first, a childhood romance or a vision of myself at age thirty.

Advertisement

Tot: 0.303s; Tpl: 0.022s; cc: 26; qc: 135; dbt: 0.1598s; 1; m:domysql w:travelblog (10.17.0.13); sld: 1;

; mem: 1.8mb

david

non-member comment

Still Brave

Aww, You're still being brave, bold and beautiful... Miss ya, David