Advertisement

Published: December 7th 2007

Camping at Karakuli & The Zen of Rubbish Collecting

"No pictures," commands a young officer in an olive green uniform and just out of diapers .

"I only want to photograph the mountains, and they're on the Pakistani side anyways."

"No pictures!"

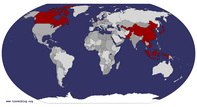

Welcome to the People's Republic of China. One by one passing the officers, we file into a shed to show our passports and have our bags searched. A busload of Chinese tourists returns from atop the pass, a long daytrip excursion, and tumble into the street taking photos of each other. "Oh, are Chinese tourists premitted?" I inquire of the young unyielding guard who at my prompting chases after the group yelling orders. Meanwhile I take some photographs of the majestic pass. The 600km stretch of the KKH in Pakistan, climbing through narrow valleys and rugged landscape and the tumbling Indus and Hunza rivers gives way to a broad valley in Xinjiang province, descending as far as the eye can see past Kyrghiz settlements scattered along the irridescent Tashkurgan flowing towards the Tamalakan Basin. I set my watch ahead one hour though officialdom, bus and train schedules, hotels, run on Beijing time, a further two hours ahead.

Pakistan - Xinjiang border

Pakistan - Xinjiang border

an illegal picture taken in China of the Pamirs in PakistanWe pull into the customs and immigration office on the outskirts of town around six o'clock. "Do you have any fruit?" asks the young agent. "I'm afraid I'll have to destroy these apples, " she says with all seriousness. I have to wonder what the mammoth sized cargo trucks are transporting. I offer to destroy one of the apples myself, starving after a non-stop nine hour journey with only a packet of biscuits. She examines the remaining apples as though they were moon rocks. My luggage is checked once more and though their cases art much smaller the Pakistani's have their luggage thoroughly examined and their persons padded down. The five young men, who'd arrived at the depot together in Sust play dumb, "no English," they answer. "Are you friends?" asks the agent of one man. "No," he shakes his head. Its discovered he is carrying loose in his pocket over a grand in American fifty dollar billls.

There seems to be a problem with the computers and our passports are held for a further hour. While the other passengers board 4X4s headed to Kashgar, I march into town, daylight disappears behind the hills and a loudspeaker dictates a

message in a language I've never heard before. I book into the Traffic Hotel, a grungy budget option, and plan to catch a morning bus so I can witness the scenery beyond Tashkurgan. Night has fallen and the streets are poorly light, the air smells of autumn and chimney smoke. In the heart of town a broad boulevard cuts north to south lined with a few restaurants and a couple bright red awnings under which glow yellow lightbulbs to display various bread loaves and bagels. I stock up and buy a few provisions from the general store for my stay at Karakuli Lake. A little restuarant's foggy windows behind the bread and noodle stalls reveals at closer inspection, a scene right out of Dr. Zhivago. I enter and find an empty table in the corner along a mirrored wall and decorated with fake flower baskets, reflecting the purple and white baroque design of the facing walls and the customers' variety of hats, little skull caps, pointed vicar like caps with embroidery, an older man in a black wool hat the height of a country decor tea cozy. I try ordering a bowl of noodles, an easy enough task in Pakistan

where everybody is eating the same dish, but looking around, the customers each have a unique dish before them, some soups, others stews, noodles or strange stirfries. I am served five skewers of meat and a bowl of bowtie noodles with beef and vegetables. I order a bottle of beer, my first in two months, and linger, admiring the hats and the decor, the strange new faces and costumes. Down the hall an accordian techno music starts to thump and when I investigate I discover a dark backroom with black lighting and men and women dancing, arms lifted out to the side.

Early morning I wake with blocked sinuses and a sore throat followed by a marathon sneezing fit while trying to quietly pack and not disturb my slumbering roommates. A to go pack of rice and pork in hand, I board a medium sized coaster packed with college students from the east and find an empty seat in the back next to a young Japanese fellow from Tokyo on the far end of a three week vacation. The sky is a grey brown haze hardly distinguishable from the rolling landscape behind which rises a glare of sunlight. A

strip of blue comes to view glistening on the horizon, the far end of a vast pasture where hundreds of yaks, camels and goats dot the grassland their heads hidden in the blades. I am the only passenger to fetch his luggage but the entire busload once it looks past the TV to a line of yurts and a man holding the reins of a camel, alight for an opportune photo spot. The school kids hop back on the bus and speed away, revealing across the street a series of domed and beehived mudbrick tombs and lesser graves, something of a Star Wars set. A tall middle aged Khyrgyz man in a navy mao coat and matching cap approaches me and enquires, "you sleeping?" I tell him I've brought my tent and will camp up the shore a ways but take him up on his offer for lunch. The faint image of snowy mountains wavers like ghosts across the lake and beyond the pasture. My sinuses worsen. I fall asleep in the tent feeling exhausted and struggling to breath.

The sun forces its way through the mist by afternoon when I wake sweating and wander back to the yurts.

The lady of the yurt follows my approach and motions my welcome, lifting the rug flap as I enter. Five metres across, the single room dwelling is laid with simple woven rugs except around the cooking fire where a pipe climbs to an opening in the roof where the rugs are pulled aside to let in the hazy sunlight. Thin crisscrossed strips of wood support the structure's walls from which knickknacks and kitchen utensils hang. Across from the door stands a cabinet, their single piece of furniture draped in a thick red flowery blanket. Next to the door on a low primitive counter sits a two burner gas stove and next to this a small cupboard where the poorly washed cookware, food and drink are stashed away. I sit on a cushion near the fire while the woman, playing with her head scarf, rummages among the bowls and bottles before serving me a bowl of yogourt and a plate with hard bread and rock hard bagels. Her husband and I are both poured a cup of yak milk tea, lighter in colour than Pakistani chai and served without sugar. Their young boy enters and sits between us, helping himslef to

bagel slices. His parents refrain from eating in the daytime for the holy month of Ramazan.

The afternoon I set out along the lake for an adventure to the village just peeking its rooftops from the horizon but am diverted by bits of rubbish strewn all along the water's edge and clinging to the marsh. I collect two and a half large canvas bags of trash, as I used to do on the beach back home, an emotional endeavour, carrying the responsibilty, cursing the dim-wittedness of poor habits, this my one selfless gesture to atone for all my comsuming and while the gesture is begun without thought, only instinct, there follows and remains heavier on my mind the frustration and reproach I feel for society's plastic life and disregard of nature. The next day I am returned to the shore collecting a third and fourth sack when a camel pulls up and two young women from Shanghai alight, the taller asking where I'm from, what am I doing and may she join me, while her friend snaps pics with an oversized camera. Glancing anew at the beach and feeling satisfied, I wander into the pasture land and find an

agreed safe distance from where to sketch a group of camels, the very colours, a sandy beige and deep brown mix of the surrounding hillsides, munching, grinding their fat lipped mouths in a circular motion, raising and lowering their long necks. Today is a beautiful day. Cleaning the rubbish along the shore, I have given of my time and appreciation and made it my home, my responsibility, however temporary. The sun's rays dance in and out of small clouds ambling westward across the Pamirs, other clouds graze above the peaks of Maztagh Ata, its pristine face reflected in the marsh. The sun sinks behind the hills bordering Tajikistan, less than ten kilometres distance, the temperature drops and I race back to the tent, an illusion that I am not living outdoors which fails around midnight with the shivers. But it's quiet. There are no neighbours, no shops, no room mates or tour groups. The lake laps at the shore, an excited dog barks suddenly and is quiet again, the deep moan of a yak bellows across the marsh, cars and trucks slip through the night, never disturbing, but confirming that I am not yet reached the wilds.

Morning, I

wash in the cool stream where I also leave my 'motions', followed like most days, standing still and breathing and aligning my chakras. The phlegm from my sinuses has ventured into my lungs. My water bottle is empty and the sky is overcast and brown like a suspended sand storm. I gather rubbish from the tide but soon tire and sleep until afternoon. Life on the lake is quiet. Little green taxis pull up to the yurts, Chinese tourists from the East hop out, pose for pics, hop a camel for ten minutes of wild adventure and having experienced all that local life has to offer them, hop back in the cab and peel away to the next sight. I paint my sketch of the camels grazing below Maztagh Ata, boil some Pakistani chai and shortly before sunset visit the yurt for dinner. I'm served a heaping bowl of rice topped with tomato, onion and egg. The wind picks up outside but it's warm and cozy in the yurt. The door flaps, the pot of rice and veg hisses. I hagge for the use of a thick blanke and return to the tent under a yellow sky, the underbelly of

a motionless sandstorm.

The morning is grey and my illness no better. I am just in time to catch the 9 a.m. coach to Kashgar, pausing by the lakes to let out two Australian girls. Unlike aclear day when friends and family partake of the fair weather and venture outdoors to hike or swim or picnic by the lake, a grey day says, forget m. A grey day doesn't want to belooked at or partaken of. Only what lies immediately along the roadside is visible, blurring at the edges, suggesting gravel roads into the rocky terrain. The road turns, the valley narrows, white peaks waver amid the grey morning. Further on the journey twists through construction sites and unattractive villages with concrete facades, car parks and tall billboards advertising

. The bus halts undecidedly along a bazaar in Shufu where I catch my first glimpse of urban Xinjiang and its array of faces and costumes, Turkics from Mongolia, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, women standing curbside dressed in skirts and stockings and sequened polyester blouses, thick hair tied under scarves, hands on their hips, chatting to their neighbour, selling cool drinks from freezers or fresh fruits displayed on long tables.

Without a Hat You are Nobody in Kashgar

I'm let out on the outskirts of downtown and unable to orient myself, wander into the busier blocks asking news stands for directions. An American couple wrapped around each other on a crowded traffic circle, necking as though on honeymoon, elicit from me a mumbled under my breath, 'find a room', before realizing I'm standing by the hotel gates. I check in. It's thursday. I've arrived a few days before the Sunday market to soak in what I can of local life and to beat the weekend wave of crowds my guide book warns of. I pass the afternoon wandering the tree-lined avenues in flip flops unaccustomed to pavement. My muscles tire quickly of the city's stop and go rhythm and crowded curbs. A visit the bookstore is made in anticipation of the long bus rides across western China.

The following day on my wanderings I'm accompanied by a young American woman, Alison, who's been teaching several years in Beijing and has a good grasp of Chinese. She tells me of her various employers; a lucky break with a two week summer camp that financed her flight, a boss that let her go to be replaced by the boss' incompetent ex-boyfriend whom she hoped to woo back. We explore the spice market on the edge of Old Town and the adjacent row of hat shops, easily the most photogenic place in town for people-watching. The sunlight filters through the awnings, bulk bins of fruit candies, chcoloate, seeds, nuts, spices and teas create quilt patches. A dozen shops display the same bins of saffron, cumin, candied peanuts, saltines, figs in various quilted patterns. The shop keepers attempt lazily to lure my tourist dollar. The nearby hat shops, not to be confused with those in the squares around Idkah Mosque or the covered malls of the Sunday - actually everyday - market, display on hooks or wooden knobs or uptiurnd waste bins a half dozen styles of head wear. Most abundant appers to be the four sided peaked embroidered cap that recalls to mind a church cardinal. They tend to be black with white and green stitching, popular among the local men but decidely untouched by tourists. While second in popularity would be the simple skull caps, the shops tend more to dicplay shelf after shelf of black wool hats, some with brown trim, some taller than others, others tall enough to smuggle a samovar across the border.In equal number but in contrasting effect are the various other fur and wool caps, in white,beige or black, with or without earflaps, strings, showy tufts and finally more familiar to westerners, stacks of 'paperboy' caps and old man boulder hats, the former in dark browns, the latter in grey and black plaid. Some of the fur caps are of loud dimensions requiring a degree of personality, necessitating adequate level of seriousness, a little humour and at least two years of study of Russian literature. Not until Sunday do I find my hat, a wool cap the shape and size of a fancy folded serviette. There seems to be no other like it in Kashgar and in a town full of hats where one's faith and ethnicity are to be found in its manufacture, I am met with scrutiny, the lone Russian emigre to Kazakhstan.

Alison and I weave our way through the food market, the tangle of carts and wagons, horses and tractor engines pushing and pulling their way through the tables of fruit and veg, the butcher's blocks, the noodle vendors and the popular cake stalls. We cross Jiefang Lu and enter the plaza fronting Idkah Mosque, its yellow gate and minarets tucked among a row of trees, the city's centre piece now dwarfed rather than embellished by the construction of a modern Chinese plaza with steps leading nowhere and flower beds where lines benches crowded with Uiygher men who've nothing better to do, sit and chat and watch the tourists on parade while they wait for the call to prayer. The evr present photo booths offer the subject a variety of poses, on horseback, camel back or seated in an elaborate cart.

A tall young man in front of the mosque gate informs tourists to return after prayer time, some two hours later. In Egypt, in Turkey, in Pakistan I was never told not to enter during prayer time where it was simply a matter of logic and following posted instructions, not to disturb the rows prostrate on their rugs. We find a spicy Uiygher restaurant on Renmin Xi Lu, windowless, the walls coated in perspiration. We venture into a large underground supermarket and explore the aisles of colourful packets, and after inqiring as to some cheese, are directed to a bag of hard yogourt candies from Mongolia.

Back in he hotel lobby I encounter Sean who has just arrived in town courtesy of a jeep hired by a Swiss woman. "Mireille?" I ask. She leads us to a food market she'd uncovered the day before. She recounts for us her frustrating and shameful day trip out to Karakuli Lake, the jeep she hired for more than a hunderd dollars, the driver who spoke no English and who grew unreasonably angry when Mireille asked could she help lift a Swiss couple back to the city who's bus carrying their luggage had departed the checkpoint without them. Off Renmin Xi Lu, down a side street of spice shops, electronic shops, and cool drinks stalls we compare the kitchens either side of the aisle, hissing and boiling and frying, noodles, hot pots, fish and trays of vinegared veggies. The three of us fetch our desired late lunches and sip copious amounts of tea, lingering, chatting, people watching, soaking up the atmosphere, prolonging the inevitable slog through the crowded streets. Convenient and alluring, over the next few days I return for lunch again and again on my own or with other travelers and sit at the popular Uiygher stall, serving up heaping bowls of spicy noodles, where I learn the symbols and pronunciation for luomien, somien and guomien, pulling noodles, friend noodles and a mixed noodle dish. I sit and watch the young men taking customers' orders, how each staff has his or her own role, whether chopping or frying, pouring tea, washing dishes or the most entertaining, a young man with a fine little rump and a wee moustache busy kneading and rolling the dough into balls and pulling the noodles into three foot long threads. After he gathers a half dozen threads, he grabs both ends and whips the middle against the counter with a loud bang. He doesn't know I'm looking at his backside. Noodles can be only so entertaining. All the while the boss sits to the side watching his young employees with a stern eye and collects patrons' bills. The young employees smile when I arrive for the third day in a row and help teach me the various noodle dishes, luomien, suomien and guomien. However, in the ensuing weeks when I attempt to match these terms to the symbols or pictures, I am inevitably served the same spicy bowl of noodles, a strange reincarnate of Pakistan's rice and dhal.

Mireille, Sean and I meet Allison in front of the mosque but forgo the entry at 20RMB a pop and cross the street to the spice market and stroll into the Old Town. I guide my friends around the ticket booths and into the shaded quiet back lanes, a look at how things may have used to be. I can't help but regard Kashgar as a walled amusement park, the Han operate the busses, the wickets, the rides, while the Uiyghers carry on a semblance of their daily life believing themselves to be shop owners or farmers or restraunters when in fact they are the amusement. The Han account for 30% of the population in Kashgar, dressed as pharmacists, hotel owners, bankers, police and military. I can only assume the children mix together at school and their parnets too in the factories and in the markets but not once do I witness a mixed group out enjoying the night air or a multi-ethnic couple walking hand in hand. I photograph the children playing in the lanes with a stick or with little plastic motorbikes. Their faces hide nothing, big eyed, lips expressive, most keen to be photographed. I am reluctant to ask the men and whenever I ask the women, they are quick to answer in the negative. So I take endless shots of the younger generation scampering in the shadows of two hundred year old homes. Stretches of the Old Town have been given a face lift, the alley dotted with golden cobble stones, guiding the tours past house fronts bearing plaques that justify rebuilding century old homesd into hat shops and carpet shops and bric-a-brac shops. Sean & I, trying to cut a path across the Old Town in search of the Sunday Market, happen upoin a Chinese tour group swarming a young defenceless girl in the alley, clicking their tongues to grab her attention and flashing their oversized zoom lenses inches from her poor face. I surprised myself and let the whole scene unravel without strangling the tourist, without damaging his camera, without even screaming down his throat. I wonder how much autonomy the Uiygher have in Xinjiang, how much control they have over their people's future, which for the moment seems doomed to become an endless series of roadside attractions for busloads on the move. I find it shameful and sickening, this China of bullying entrepreneurs and ignorant polluters.

We wander further reaching the blue and white tiled mausoleum of an eleventh century muslim poet and scholar. The entry fee is 30RMB and no doubt the explanations will not cater to non-Chinese. The toll booth is empty and for a few moments I taste freedom, snapping pics in the rose garden before an irate young woamn returns, "ticket! ticket! menpyo!" As dusk falls we discover a theatre with nightly showings of minority dancers and musicians in frilly shiney costumes. Too dear for Sean and I, instead we find a table in a BBQ tent in the theatre's parking lot, choose a bunch of skewers, vegetable, tofu, bread, meat, each painted in spice and cooked over the coals. We sit several hours washing down the tastey morsels with shots of Xinjiang beer. Mireille recounts tales of her field work with the Red Cross in Georgia, Bosnia and Africa. We discuss war and her new job in Geneva working with asylum seekers, the stress of the younger generation who grow up with a new education, a new system of thought often in sharp contrast to what their parents believe and preach to them at home. The three of us each share our mild experiences with meditation practice. I admire Sean who takes his Buddhism more seriously and refrains from meat. We share experiences of witnessing spirits and discuss whether or not free will exists. Sean and I are similarly convinced that all 'fate' is predetermined by nature, or logic, or cause and effect, however one wishes to label the laws and forces of nature. Mireille is astounded and questions why does she bother, why should anyone for that matter, bother to execute positive change in the world. Sean, using somewhat cerebral terminology, explains that an individual's actions are part and parcel of nature, resulting from their attitudes, resulting from their previous experiences, education, upbringing and their will to effect positive change is only logic. Mireille will soon turn forty. She is happy with her choices and in hindsight can see she has progressed, obtained and refined stronger skills. I will soon turn thirty and am quite happy just to be a traveler for the moment.

Mireille boards a morning flight the next day to Islamabad and then back to work on Monday. Sean and I spend Sunday together, wandering the early houred back streets for clues of the live stock market misplaced in both our travel guides. A German - Australian couple with the latest edition show us it has moved several blocks out of town and we all share a cab, arriving mid-morning behind the tour groups. Enclosed in a brick wall beyond the carpark full of vegetable stands and general market noise, tractors and blue pick-ups haul livestock into a large dirt yard, two footbal fields lined end to end. Herds of goats are tied in orgnanized knots shoulder to shoulder, their heads woven in a geometric weave watching their neighbour's backside, donkey carts pull up one by one in a sectioned off zone where old men and their grandsons clamper aboard and take them for a test drive, whip in hand, bells 'a jingling. Western tour groups crowd the locals snapping close-ups of the weathered faces and exotic headware. The cattle buyers eye the merchandise and pump hands vigorously with the sellers, working out an agreed price. To one corner of the cattle yard, stand four small yaks, three white, one black and two camels. 3500RMB for the three year old male, 2000rmb for the two year old female, presuming our communication was anywhere near the mark. One might expect farm equipment or at least handi-crafts for sale but besides the livestock pen there is little to divert the crowds. The morning's parade of countryside folk continues to roll in, donkey carts, hoofs pattering the concrete, sheep herds and black sedans, always a glum faced Han behind the horn.

Thus far my initiation into Chinese travel, compared with her neighbour Pakistan - and further distant travels in South East Asia - has been less than I'd hoped. My guide book has fallen behind the times. The popular cafes, restaurants, guesthouses have been replaced, their prices have escalated. Hotel rooms are over-priced for what they offer and sightseeing as an independent traveler is beyond one's means. Entry fees and transportation out to the sights are fixed at tolls on par with western countries. Perhaps most discouraging, because after all some sights are worth the entry fee, the troublesome journey through wonderous landscape, and considering I'm still somewhat young and can afford the less than luxurious basement beds and dorms without showers, is the rough manner of the local swindling tourist trade. So I reexamine the guide books and translate their exagerated enthusiasm, convert the prices with the past few years' inflation and decide just how much deceit I'm willing to accept from hotel owners and taxi drivers. Having discovered the reality of Kashgar, or rather, having replaced its exotic mix of ethnics in a remote and unknown landscape conjured from history books with today's silk route theme park reincarnation, I decide against further travel along the south silk route. Yarkand and Khotan will remain exotic and wonderous, smaller versions of a Kashgar I used to envision reached at a long journey's end by camel caravan ladened with spices. My plan to circumvent the Tamalakan Basin and to cross the Kunluns, a five day coach journey rattling its way in the dark to a hired jeep waiting in the sand dunes to overcharge me the last stint to a ruined oasis where the Hans are standing by to hand me an entry ticket to a fenced in ghost town with plaques and tourist kitsch souvenir stalls, kinda lost its appeal.

I catch a sleeper bound for Kuche, a twenty dollar upper berth with a thin mattress and a frame three inches shorter than me. My head is raised above the feet compartment of my neighbour. Cramped, I recall the bound foot beauties of an earlier China. A slapstick kung fu flick dubbed and subtitled in Mandarin entertains the passengers as the bus finally grumbles into gear, an hour late, the pale sun decsending over the city outskirts. I watch a car chase scene involving a young nun, a chubby slow-witted man driving a van full of snakes and the anatgonists, two men in suits and sunglasses before returning to the pages of nineteenth century Wessex and the trials and tribulations of Tess Durbyfield. What felt sacreligious in Pakistan, turning to a work of fiction to escape my surroundings, is a necessity traveling western China. By morning, whether according to the sun or to Beijing I am no longer certain, the bus halts on a strip of highway several miles outside Kuche where a half dozen passengers, myself included, alight before a low metal arch preventing heavy truck traffic from entering town. A few of us hail a passing pick-up and motor down the slope into a dry green neighbourhood of mudbrick dewellings known as Old Town, before crossing a simple river into new town, the ever common construcrtion of bathroom tile facades and wide empty boulevards. Over a bowl of noodles in a shop next to the coach station where the town's cheapest motel has upped their charges, I brainstorm my options while a taxi driver pesters me over and over to accept his lift to the Kirgil Thousand Buddha Grottoes. I book a sleeper for the evening on to Turpan before making a call at CITS, the friendly English speaking government sponsored travel agency, which seems to have disappeared so I find my way to the local bus station for a cheaper alternative out to the caves.

To avoid the access road's strange cross bar, the bus wobbles off the drag into a sand course and follows a series of dirt tracks criss crossing construction sistes along a future toll way cut through a changing landscape of rock formations and glowing red cliff faces, a winding river and grey grey skies. I'm woken an hour and a half outside Kuche, among a block of forgotten shop fronts and souls dwelling this neighbourhood between nowheres. The motor rickshaw drivers have all banded together charging an unnegotiable 15RMB for an 11km trip. We take a short cut through a wide gravel yard plowed with zig zagging roads and bumps and jumps. I hold the bars and try to keep my neck from snapping. A sealed road cuts a pass through the low hills of beige loess earth and descends into a valley, a narrow thread of river feeds a scattered grove of trees and disappears beyond the low mountain range stretching east to west. The rickshaw puls up to a ticket booth. There are no tour groups, no coaches, only a single Chinese family being lead up the hillside and shown inside the caves. A chubby girl races up the stairway to lead me on my private tour, panting, catching her breath, fumbling with the keys. She speaks no English, her skills as guide, as art historian are minimal. She reveals the murals, or rather what remains of the long since looted masterpieces, scratched green and turquoise buddhas, flowing apsaras, hints of musicians and mythical creatures, fading into amnesia. She unlocks the treasures, shines a torch on the back walls and stands patiently while I give adequate time to honour the peeling relics. Back in the village, returning by the same unforgiving gravel path, I take a seat under a covered verandah on the roadside next to a group of men playing cards and oredr a bowl of longmien. While I slurp my spicy noodles and tasy meat, bus after bus, and cargo trucks, zips past, and little green coaches that pull into town only to turn round and return in the opposite direction I'm headed. It's after four before a coach bound for Kuche pulls up. I keep a close eye on my watch, especially as we trundle across the construction zone bordering town, pulling in at 6, or 8pm Beijing time. The sleeper destined for Turpan is departing at that very moment from the other end of town. "Go! Go! Go!" I shout into the taxi pointing vigorously down the road, "just drive - straight!" fumbling for my ticket to explain where I have to be. "That's it!" I point to a long black coach cutting a left turn across the intersection before us. The driver pulls a U turn and speeds past the coach and we signal him to pull onto the shoulder. Strangely, my rucksack has remained stowed away under the bus where I left it that morning.

Turpan, City of Raisins

I find my berth and settle in for the night. Tess Durbyfield's bastard son is burried, she becomes a milk maid and meets up again with the parson's son, Angel Clare, her hero. At 5am Beijing time, 3am local time, the driver wakes me. I'm the only passenger to alight. He points to a bus station black and shuttered. The lady who sold me the ticket said I would need to change busses at 7am , to cover the last 35km into town. Parked by the curb is a taxi cab insisting I pay 100RMB for the 65km journey into Turpan. A single lightbulb shines over the glass counter top of the only opened shop. A young couple appears on the curb burt I am tired and unsure of their story. A second cab pulls up asking 60RMB and I hop in. A few miles down the main road we veer off into the darkness on a treelined side road, headlights reflecting on the creepy crawly branches climbing out of the ditches. Watermelons lie smashes along the ashphalt like bloody roadkill. We pass their killer, an overloaded sluggish farm vehicle. The taxi driver helps me with my luggage and I crash in a corner of the Turpan Hotel lobby. The staff are waking, gift shop awnings roll up with a clatter, lights turn on, mops swish across the floor and the receptionist calls me over. I can check-in. I opt for a single with a hot shower, a corner basement hide-away with a view of the tour bus exhaust fumes. Following a few hours nap I search out a quiet space in the gardens behind the hotel to complete a few tai chi exercises. Deep breaths. The dark blue chakra, the third eye, feels blocked, ligaments and muscle twist, right shoulder pulls back, a strange sensation in the trapezius and an empty feeling in my left gut. Backpacking is poor on one's posture. Bear and grin it. Another branch of John's cafe serves up coffee and hald cooked banana pancakes under the vine trellises out back Turpan Hotel. I lounge until midday sharing lunch with an Italian, Dario, whose credit cards have failed him and who has spent all morning on the internet searching alternate means to transfer funds from back home.

I rent a hard seat jalopy for the afternoon and pedal west out of town to the ancient ruins of Jaiohe. The ride is refreshing, divorced of taxis and busses, independent. The road decsends to a river which cuts Jiaohe from the surrounding land, forming a small island of dry earth high above the vineyards and narrow farm yards of the river valley. Beyond the souvenir stands and electronic turnstile, a paved walkway lined with caution signs climbs to the dry earthen walls of the ruined old prefectural capital. The plain clothes guards repeat for the hundredth time that hour to a group of Chines tourists to stay on the path. Plaques label the administrative district, the childrens' cemetery, the residential district and to the north, the temple district. There are no guided tours and little information is provided. Administration seems more concerned with obtaining money than with educating visitors. I wander the winding paths and explore, when out of ishgt of the guards, a few sandy trails into the ruins. The views down the cliffside to the poplar lined chasm hugging the river looks far more interesting than the sun dried ancient city. I pedal back via farm fields and quiet biways, grape vines as far as the eye can see and quaint neighbourhoods of simple mud brick dwellings. Behind the tall wrought iron gates and tiled lintels with simple paintings of mosques and grape leaves, I spy in the family courtyards hundreds of long vines hanging row after row from high racks.

In the evening I stroll People's Square where a colourfully light fountain dances to traditional Chinese music delighting the young couples necking on the benches. Young men shoot billiards in the open-air and stalls make brisk business selling drinks and skewers of spicy meat and veg and tofu. I relax amid the circling crowds, noting the locals from the tourists, the former generally young couples flirting, the latter roaming in packs in search of ice creams.

There are several sights scattered in the countryside around Turpan, Buddhist grottoes, flaming red landscapes, old city ruins, mosques and temples. A day's tour I learn would take upwards of ten hours, spent mostly aboard the coach, and stopping at several uninteresting plastic amusement sights, transport and entry fees would total over fifty bucks US and the guide(s) would be speaking Chinese. Westerners have arrived to Xinjiang in tour groups banded together by nationality on a thematic two to three week expedition. Alas, I limit myself to the fields and muslim neighbourhoiod south-east of town and explore aboard a rented bicycle, admiring the calm back streets and the old faces. There is little traffic, little commerce, a butcher, a baker, a general store huddled at a main cross roads. There seesm to be little else besides the grape harvest, students return from school to help their grandmothers sort raisins in whicker baskets. I pass several tall tiled mosque fronts but never hear the call to prayer. I happen upon an old cemetery, a raised clay yard with unearthed bones and a few sand castle tombs and pedal further east to search out Emin Minaret, the only Islamic tower in all of China, standing 44m high, dating back to 1777 when General Emin Khoja's son wanted to commemorate the brave leader's defense of the unification of China. I spy the minaret across a vast vineyard and eventually find my way to the gates to discover an inflated entry ticket cost, the price of a hotel room or a dinner for two.

Dunhuang done right

Highways have improved drastically since my guidebook was published only five years back. The sleeper bus pulls into town after fourteen hours on the open road. Like Kashgar and Turpan, there is a Joe's Information cafe outside the hotel in Dunhuang. The coffee is cheapest in the latter, the banana pancakes at all three come half cooked even when given instrunctions to do otherwise. I learn from a friendly Dutch husband and wife of the public busses running out to the world famous Buddhist caves despite the Hotel receptionist who'd informed me I'd have to wait until next day to catch the guided tour group. I've studied Art, I've studied Religion, I've studied History and Archaeology. I know all about the Magao Caves outside Dunhuang amd I AM PUMPED. Entry fee 180rmb - deflating a little. There are no majestic cliff faces. The "Singing Sand Mountains", so named for their mica deposits that yield a sparkle in just the right angle of sunlight lie hidden in the sandstorm swept sky and behind locked doors and a protective ashphalt siding, even the river has dried up and looks rediculous cutting a wide sandy path across the scenic shopping street approach way - deflating more. But I pay the entry and approach the inner gate where I am told to wait for the next English tour group. I learn from various travelers and piece together the information, that there are all together 492 grottoes, sixty or seventy of which are open to the public, twenty-five to thirty of which you can expect your guide to lead you to. For each other cave you must hire a private guide and pay a small fortune to have its door unlocked and its treasures revealed. During one of three daily two hour guided tours, you can expect to visit - and have explained to you - eight caves. I AM DEFLATED.

I understand though, the tour guides and the authorities do their best to accomodate the heavy traffic of tour groups while ensuring that the cultural relics withstand the elements. I join two English tours and jump in with the Chinese herds, listen to over four hours of explanation and leave with a renewed appreciation for the old Silk Route. The Thousand Buddha Grottoes dates as far back as the fourth century, its craftsmen artists from present day Afghanistan, and commisions for new caves continued over the next millenium. Although several 'Thousand Buddha Caves" sites exist in several provinces of China, the Magao caves are special for their location, an important transport hub on the Silk Route later abandoned in the fourteenth century, and not to be uncovered until European Archaeologist / Treasure Hunters arrived in the early twentieth century. Tens of thousands of sutras, silk paintings and statues were removed but what remains still manages to paint a fascinating picture of the religious, social, economic and political conditions spanning ten decades of China's past. Some of the greatest works of sculpture and painting date to the Tang dynasty, two examples of which illustrate the political importance of these caves. Three Tang emperors, Taizong, Wu and Xuanzong departed from the traditional ascension to the throne. Having usurped command of the empire, they commisioned some of the most awe-inspiring caves in which were housed images of Boddhisatvas in their likeness, communicating the notion that they were pious and noble leaders. Empress Wu, the only female emperor in China's history, erected a 100 foot Buddha in her likeness and Xuanzong commisioned a 75 foot Buddha. Murals of the Heavenly paradise filled with musicians and dancers closely parallel images of the royal court and other paintings include the many strange new ethnic faces that were joining the Middle Kingdom. Still other images give reference to Daoism and Confucianism, philosophies native to China, pointing out the foreign roots of Buddhism and its manner of introduction through the mixing of philosophies and moral tales and altered representations.

To Conclude

I found the romance of The Old Silk Route and camel caravans has been replaced by ticket booths and tour groups under the administration of the Chinese who continue to control the local "minorities". When it costs so much to venture out to these sights, only to be denied access to the majority of the relics, sadly, for a deeper appreciation of Dunhuangology, (real word) a visit to the Louvre or the British Museum might be more worth while.

Advertisement

Tot: 0.124s; Tpl: 0.023s; cc: 11; qc: 31; dbt: 0.0495s; 1; m:domysql w:travelblog (10.17.0.13); sld: 1;

; mem: 1.3mb

Maz

non-member comment

My Vicarious Hero

Hey Kevers, Do you know when writing the comment title I had to look up the spelling of the word hero. I, at first, spelt it the Japanese boy's name's way, HiRo. I've never replied to anyones travel blog (or any kind of blog) so I don't know if I only have only this tiny little display window, like those fucking answering machines that go beep 'hi kev, yeah,so this is maz and well, yeah....BEEP. and I don't even know if this message I'm writing is for Kevin or...... BEEP. or the other people who think kevin is... BEEP. Anyway, the little window keeps moving down so I think I can write forever and ever, amen. For Kevin You write eloquently and travel intelligently. Gotta go, I have to deliver a jacket to a man who has no shoes. In summary, Kevin, you're great. I travel vicariously through BEEEEEEEEEEEEEp.