Advertisement

Published: August 6th 2010

Walk

Walk

Walking with Nicholas and Matayo, two of my guides, on the TransRift TrailMy name is Jeruto Jepyator: the woman who travels and the one who opens the way. I was given these two Kalenjin names independently, by two different people on the same day of my walk across the Great Rift Valley. Such was the impact of being a white Western female ‘footing’ through this land. Tourists are rare; wzungu (white) people even more so, although on many stretches of my walk there were distant memories and recollections of one or another mzungu who had gone before. I was the first person this century to open the way yet I was following both the ghosts of others and the tangible real knowledge of my young Tugen guides. This was not just my journey but theirs as they opened up the way to a new future for themselves. Even now as I write this I know I must be conscious of the dangers of colonial ownership. This thesis is written in my words but based on the knowledge of others.

I found that I could not help but be conscious of my white identity as I travelled with my Tugen guides. It was a topic of conversation and laughter most of the time

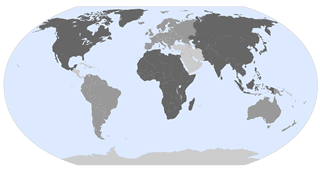

Transect

Transect

Map transect of the walk across the Rift Valleyas we each explored our differences in culture and outlook. The act of walking opened up a relaxed and fluid communication between myself and my guides. Rather than formal structured interviews, I soon found this was a methodology in itself that made a more equal partnership between interviewer and interviewee.

I wondered at times how my colonial predecessors had viewed the land and how they related to the Tugen people. On the part of the people that I met I found they were on the whole delighted that I was there. The older people had good memories of the wzungu presence and still to today look to them as symbols of respect. Wzungu are benefactors; carriers of wealth, bringers of education and the Christian religion.

The 140km walk formed a cultural and environmental transect across the Tugen lands of the MidRift. It was trodden in several stages due to limitations of the available technology as I had to return to base to charge camera batteries. However this allowed time for reflection and the recharging of my own mental and physical batteries. I was following the dream of a friend, a previous student, and now my mentor, William Kimosop,

Last forest

Last forest

Maize planted under the last remnants of forest at Mochongoiwho is the Chief Warden for Baringo and Koibatek Districts in Kenya who wanted to re-establish the old trails across the Rift Valley and open them and his homelands to tourism, These trails physically link the dramatic and diverse landscapes that are the Rift Valley but I was to find that they link wildlife, people and cultures through space and time. They form a network of paths that provide corridors of attachment and association and have the potential to form new bonds.

As I walked I observed the changing landscapes and found similarities and differences in the highs and lows of the trail: both physical and metaphorical. As I crossed the rift I talked with and filmed many people along the way trying to understand the links between culture and environment and the changing knowledge that rapid development has brought to the Tugen people.

Mochongoi to Nayalilpuch The trail starts at Mochongoi on the Eastern escarpment of the Laikipia plateau. Here the forest has recently been cleared to make way for a resettlement scheme. Burnt stumps of grand ancient trees stand forlornly in the midst of maize fields. Other timber from the forest is used to enclose plots

protea

protea

Protea on the slopes near Mochongoiof land and for wooden shacks -new homes for displaced settlers from other areas in Kenya. The government reallocated this land about 3 years ago but there is an uneasiness about the area as Kikuyu, Kalenjin and Luo reside together creating new neighbours. I was to find that the two extremes of the valley where tribes mix were the only places where I felt threatened in any way on my traverse. At Mochongoi a passing drunkard invaded our private campsite and was politely tolerated by my companions until they realised that I was disturbed by the commotion. The Tugen people dislike disturbance and there is an underlying trait of tolerance to people and wildlife. Here in Mochongoi the family with whom I stayed was prospering. Sylvia, a young Tugen girl, told me how her family had found good fertile land to grow crops after they had migrated from the arid lands of Sandai, my study village near Bogoria. But to create this prosperity the forest had been cleared and now elephants come into conflict with the new landowners, where once they could just roam free.

The descent from Mochongoi to the Waseges river is steep. I walked slowly, picking

Ladybirds

Ladybirds

Ladybirds near Mochongoimy way, yet I knew my young companions would have run down the slopes. These high altitude lands with steep slopes are the breeding grounds for Kenyan athletes. On many occasions when I asked how long a section of my trek would take the answer was ambiguous. I later worked out that a half an hour journey in ‘their’ time was probably two to three hours for me, particularly on the steep ascents and descents. The mental perception of distance was normally an over estimate which meant that many of my planned day treks were short. Ina practical sense I was content with this as it left me more time to talk to people along the way.

At the top of the escarpment slopes there was a belt of Protea

(Protea caffra Kilimandscharica) trees in flower. Protea species are more commonly associated with the Cape flora of South Africa however there are several species endemic to tropical sub-Saharan Africa. Across the rift I was to find many such pockets of biological interest and value. The world tends to focus on the larger issues and regions of high biodiversity whilst small gems glitter and remain vulnerable.

As I walked

Waseges

Waseges

Waseges village where the landscape has changed from grass to scrubacross the rift my guides also pointed out some of the local plants of medicinal value. The Tugen people still use traditional herbs and plants as dawa (medicine) and many people I talked to were familiar with plants or knew who to see to get traditional dawa. One plant with succulent green stems is a powerful medicine for malaria, another I was told is a natural cure for stomach amoeba.

Within a couple of hours of leaving Mochongoi we had descended 1000 metres and the cool of the highlands was replaced with a more arid environment, although still not as severe as the Bogoria and Kerio valleys as I was to find later. The people here still have a permanent river and grazing. Their environment has changed but they maintain a warmth and hospitality derived from traditional values. At the village of Waseges I was offered mursik, the local fermented milk drink, as I interviewed an old mzee. He remembered this land when it was pure grassland, with few acacia. This story I was to hear repeated across the rift. Today the felling of trees for charcoal burning is criticised yet within memory this was a treeless place. At

malaria cure

malaria cure

This plant is used to cure malariawhat stage of succession should conservation be maintained? Here there is a good example of changing values. Trees are now needed to ‘bring rain’. The environment is ever evolving. What is optimal depends on a range of factors: human and environmental. When I asked about wildlife the old man remembered times when kudu, rhino, giraffe and lion could be found here. Now they are all gone, driven away by increasing population. People are trying to evolve, construct new lives. Within three to four generations lifestyles and livelihoods have changed, new knowledge is learnt from schooling and experience. Traditional knowledge and values become obsolete and tribal identity is subsumed into a hybrid way of living.

Further along the ridge is Nyalilpuch, meaning ‘green for nothing’ or evergreen to illustrate the richness of this highland above the arid lands in the valley below. Yet I came to this place at the end of a drought so the grey dust replaced rich grasslands. This area has been settled for over 50 years with agriculture replace the traditional pastoral practices, cattle and goats are still valued but crops of maize and millet have changed traditional ways. Transhumance is now rarely practiced although I

Hannington's View

Hannington's View

This viewpoint is named after Bishop Hannington, a 19th century missionarywas told a few nomadic people still exist. At one time a man may have had three homes (and three or more wives) for different seasons. He would move his cattle depending on the season and availability of grazing and water. As the Maasai still do today he would migrate alongside the wildlife looking for the best pasture.

Nyalilpuch is also the edge of the Soracho escarpment and provides wonderful views over Lake Bogoria and to the Tugen Hills beyond. This is Hannigton’s View and I had the sense of following in colonial footsteps. Bishop Hannington had passed this way on his epic journey as a missionary to Uganda in 1885, and a previous name for Lake Bogoria was Lake Hannington. In Uganda, he and his team were subsequently killed as he preached in the name of the Western Christian god. Later, in 1892, J.W. Gregory, a British geologist, considered Lake Bogoria “the most beautiful view in Africa”.

This part of Kenya has some of the most spectacular and varied scenery within a small area but most importantly for tourism people can get out of their cars and walk. Other National Parks and Reserves have dangers from large

Fig Tree Camp

Fig Tree Camp

Camping under fig trees at Lake Bogoriawildlife, lions, buffalo, hippos, etc and tourists are confined to their vehicles. In this area the lack of large mammals has meant that the area has held less appeal for tourists, however this is now being turned to its advantage by the Mid Rift Tourism and Wildlife Forum. The area still has wildlife, some such as the flamingos holding spectacular appeal, but it also has landscapes and welcoming people.

Lake Bogoria Lake Bogoria is one of a string of soda lakes that line the floor of the Rift Valley in Kenya from Lake Turkana on the Ethiopian border in the north to Lake Natron crossing the border into Tanzania in the south. All but two of the lakes are alkaline, rich in soda and the species that can exist in these lakes are specifically adapted to the harsh conditions.

Lake Bogoria National Reserve provides a sanctuary for, at times, 1.5 million lesser flamingos that inhabit the soda lakes of the Rift Valley. The lake is too alkaline for fish but spirolina can live in the harsh conditions and provide the food supply for the flamingos.

The other flagship species is the Greater Kudu, a shy illusive

Above Bogoria

Above Bogoria

Walking the trail above Lake Bogoriaantelope with long spiralled horns. It is not classed as endangered as there are large populations elsewhere in Africa but it can be seen as a success story for the Lake Bogoria Reserve. Through protection in the park and an active education centre local people have become sensitised to the intrinsic value of these animals and numbers have risen. Yet little is really known about the distribution and dispersal patterns of the kudu.

Lake Bogoria is one of the gems of the Mid Rift and receives a regular trickle of local and international tourists. The main draws are the flamingos and hot springs that ring the lake. This is an area of intense volcanic activity. The hot springs have a medicinal value for Tugens and other Kenyans. The sodaic quality of the water and the deposits on the rocks is used to cure a variety of ills including skin complaints and for mothers in childbirth. The legends that go with the lake are also hybrid between local cultural religion and Christianity. They are still performed in dance and story telling but the audience is now likely to be tourists.

However in the dry season and in times of

dancers

dancers

Lake Bogoria Dancers at Hot Springsdrought the visitors are just as likely to see livestock grazing alongside gazelles and zebra. The park is used by local people to graze their livestock when fodder outside the park runs short. Many of the farmers tell of wildlife returning home with their stock in the evening.

The lake has several beautifully positioned campsites. The most remote is at Fig Tree camp at the foot of the escarpment. I camped here after the walk down from Nyalilpuch and enjoyed watching the baboons watching us from the overhanging fig trees. The large buttressed roots of the trees dwarfed our small tents and the escarpment towered above the trees. At morning and evening we could here the flamingos swim warily into drink from the fresh water stream. But one was not wary enough as I saw the next morning as the baboons were feasting on its colourful form. Walking out from the wooded campsite the ground steams and bubbled from the volcanic springs and a sulphurous odour filled the air. The water in the lake was a bright green and bubbled in places as more underwater springs rose dangerously to the surface.

Acacia camp on the western shore provides a

Hot springs

Hot springs

Geysers edge Lake Bogoriaview northward along the length of the lake towards Loboi. Here there is a small island from which the Bogorians were supposed to have emerged. Oral traditions relate that the people that lived in Bogoria disobeyed their God (Asis). The Bogoria people were rich but refused to help the poor. However there were two families called Sogomo and Saragi who were more generous. God sent the boiling waters of the lake to overwhelm the Bogorians but allowed the Sogomo and Saragi to escape. These two families became the ancestors of the people who live around Lake Bogoria today.

Emsos People around Lake Bogoria have been affected most by the gazetting of the National Reserve. Some of the Endorois sub-tribe of Tugens were displaced from the park to other locations with a 6000KES compensation payment (£50) in 1973. To some old men this is still a contentious issue. They have memories of rich irrigated land that they once used for their shambas (enclosed farms) on the edge of the lake and maintain that this was replaced with meagre patches of land. The village of Emsos is home to some of the refugees. Of all the villages through which I passed

Cattle at Lake Bogoria

Cattle at Lake Bogoria

Local people graze their cattle in Lake Bogoria Reserve in the dry seasonEmsos was one of the most traditional in lifestyle practices and outlook. With a few exceptions, education did not reach any of the people here until only 30 years ago. Although one of my guides, Jackson Ngetich ran away from home 45 years ago to receive an education at the missionary school in Kisanana, 40km away. The villagers still bare the brunt of conflicts with wildlife because of their proximity to the park. Whilst I was in Bogoria a young man and his father were viciously attacked by a rabid hyena, the old man subsequently died. The reaction of the village showed the sensitive nature of their existence and reflected the hybrid cultural attitudes that they now possess. The immediate effect of the attack was for the villagers to angrily petition the local authority and KWS who jointly manage the park for assurances that wildlife from the park would be contained and that compensation would be given to the affected families. However three weeks later the ‘witchdoctor’ accused of ‘sending’ the hyena was murdered in the village. This shows both an understanding of the governance structure of the management of the park and surrounding district as well as more ‘traditionally’

Flamingos

Flamingos

Greater Falmingos nesting on Lake Bogoriarooted beliefs. On the part of the park authorities, every effort was made to work with the community to find a solution and request compensation from the government which can be a long and deliberated process. Compensation payments are currently undergoing review.

Younger people in Emsos have been finding ways to diversify their income opportunities. Community fish ponds have been established and stocked with Tilapia for consumption and sale. Initial resistance by the older generations as fish is not seen as a local food source was overcome. However, ongoing management of the ponds is failing due to difficulties in marketing. Emsos is the site of other Community conservation projects includes the settling up of a campsite with the aid of WWF and establishment of a series of nature trails. Emsos is bestowed with natural resources to appeal to ecotourism. A hot water stream lined with mature fig trees runs through the campsite. There are a series of bathing pools and a natural ‘swimming pool’ which, with the addition of a filter to clear the sediment, could form the basis of a spa resort. There is opportunity for further investment here to sensitively develop spa facilities. These are the hopes

Emsos

Emsos

Hot natural swimming pool at Emsosand aspirations of some of the more forward thinking of the youth in the village. But, as in many of the community projects in the area, there is a need for leadership, motivation and donor funding to make such development projects work. And there are also more basic needs to fulfil. The immediate needs for food security tend to outweigh any conservation efforts where the economic gain is less tangible or sporadic. There was a period of drought at the time I was there and people were encroaching onto some of the more fertile land of the swamp near the campsite. Mature trees were being felled and cleared for cultivation.

The young people are also in need of opportunities for further education. Ezekiel will be the first person in the village ever to attend University next year if his funding is confirmed. Small developments breed a need for more yet the resources, particularly in these remote villages, are few. Remarkably I found a constant optimism amongst many young people that eventually they would find the funding to move on.

There are two trails between Emsos and Maji Moto. The first goes via the perimeter road round the lake

goats

goats

Goats find scant vegetation for grazing near Emsosand the most popular of the hot springs and the second is a more direct route, the local shortcut between Emsos and Maaji Moto.

The shortcut trail that I followed from Emsos to Maji Moto is through extreme arid lands of sparse acacia scrub. For about two kilometres around Emsos I met women herding goats, walking with their flocks through the hot bush looking for palatable leaves. After that there is little vegetation or livestock and few dwellings in this inhospitable zone. Yet the land has been demarcated and title deeds are pending government review. I was informed that some of this barren land was the land given in compensation for the eviction of the farmers from the shores of Lake Bogoria. It was hot and arid with no vegetation under the dry looking acacia scrub. Euphorbia species lined the route and there was some planting of sisal and aloe to stop erosion. Ezekiel was introducing me to this route as the 14 kilometre trail had been his weekly road to school in Maji Moto. I found there were parallels in the lives of the young Ezekiel and Jackson Ngetich (52) in their quest for schooling out of their

cows

cows

Cows in the dry season when thre is little grazing home village of Emsos. Even after 30 years of educational developments in the area the road to education was long and almost as hard for the younger man.

Maji Moto Maji Moto like Emsos has a community campsite and a series of other community projects funded by WWF and the Finish Government. Maji Moto felt more ‘developed’ than Emsos, with a thriving secondary school and college. The people seemed to have more awareness of tourists and actively sort funding for a range of community projects. I stayed one night at the Netbon campsite which has a good set of facilities including clean toilets and warm showers fed from the natural hot springs nearby. The campsite also had three well maintained bandas (round mud houses) for visitors. Michael Kimeli, tour guide and campsite committee member, proudly told me of the achievements and benefits of the campsite to the local community. I felt that this was a serious well-established business concern. Michael, was had a good and passionate knowledge of ornithology and has contributed to many of the surveys in the Lake Bogoria area.

As I talked to people in the village that evening they were eager to tell the

Maji Moto

Maji Moto

Walking into Maji Motocamera about their lives and the difficulties of farming these arid lands. The river was a source of water for irrigation and the most fertile and productive areas were close to the river. Like most Tugens, cattle, goats and sheep were their main traditional wealth. The number of cattle that a man owns is seen as a sign of his wealth but as human population increases so does the number of livestock on communal land causing an ever increasing pressure on the amount of grazing available. Particularly in times of drought signs of overstocking are evident: thin emaciated cows and calves, bare desertified ground and a reduction in the area of the swamps. Efforts by WWF and others to introduce improved breeds of cattle are slowly taking effect but there is still a conflict between the traditional value of livestock in numbers.

From Maji Moto I was encouraged to take another female along on my camps, as a companion and a cook (many of the male tour guides had little cooking experience). So I was joined by Jerop, a young girl at college in the village learning hairdressing and dressmaking so she could set up in business. Young women

in many of the villages through which I passed aspired to earn their own living and delay the time of marriage until they had formed their own lives. As I was to get to know these women better I started to understand more about their lives and reasons for wanting independence.

At Maji Moto I changed guides but, such was his enthusiasm to learn about the next part of the Trans-Rift Trail, Jackson Ngetich requested to come along. My new guides were Matayo and Chris both young from the Kipnyigeu ageset. For the following sections of the walk I was also trialling the use of donkeys to transport our luggage as access to our next few campsites was difficult by vehicle. This was a resurrecting of the mode of transport of my colonial forebears as well as an experiment in designing a new trek for ecotourist of the future. However the skill of handling and packing donkeys has been lost over the generations in this area which caused us some consternation and laughter at first. The donkeys’ pace was slow and our walk matched, but in the heat this did not concern me. People in the area regularly walked

William at Kamar

William at Kamar

William Kimosop describes the trail to the villages in Kamarlong distances to fetch water, wood or to go to clinics or market.

This section of the trail, from Maji Moto to Radat was hot and arid. The landscape was mainly acacia scrub and there were sections of severely eroded land. Water was an important resource and rivers and water sources a precious commodity. Water for washing, irrigation, livestock and consumption came from the same sources, normally muddy looking dams or rivers. In the heat I valued my clean drinking water more than anything.

Kamar After a long day, but a short distance, I arrived at the sleepy village of Kamar in the early afternoon. I decided to camp here to meet the people and see the local wildlife attraction. Just beyond the village were two large reservoirs. One was built by a white colonial officer in the 1950s and the other created in the 1980s. These were the sole water source within a 10 kilometre radius. They were used to water livestock and human consumption but were a small sanctuary for a range of birdlife and, despite the distance to other water, a small population of crocodiles. When I talked to the assistant chief he proudly told

Crocodile

Crocodile

Crocodile in the pandam at Kamarme about the efforts of the community to coexist with the wildlife even though their goats and dogs were on the crocodiles’ menu. Their preferred solution to the problem of the conflict was to try to find funding for a third dam that they could fence off and to which they hoped to transport and enclose the crocodiles.

I was given a warm welcome to Kamar. The residents were delighted to welcome me on my long trek across the Rift Valley. I was a novelty: a white woman walking a long distance; and seen as an ambassador for other tourists who would follow after. One eloquent beautiful young woman, Jennifer, told me about her life in Kamar. She was a qualified teacher but had found it difficult to get a teaching job in the area. She had three young children and ran a small kitchen selling tea and chapattis to raise money to support her family and husband. This tale of a woman looking after her extended family was not uncommon. These rural intelligent Kenyan women often acted as homemaker, farmer and breadwinner in an essentially patriarchal society where male traditional values were being eroded.

From Kamar I

Water

Water

Raphael drinking water straight from the riverwas following the road of Arap Leso (Meaning someone who wears a leso or waistband) the white Baringo District Officer who, in 1951, had attempted to construct a road through to Radat but had been defeated by the difficult terrain and the River Molo. This road initially crossed a series of ridges and went around the edge of shambas (farms) with sisal hedging. Some areas shone silver with the branches and thorns of whistling thorn acacia (Acacia drepana lopium). Large herds of goats browsed on the low acacia shrubs.

Molos As I descended a steep slope to the village of Molos the primary school children were finishing their lunch of githeri - a Kenyan dish of maize and beans. When they saw me I was greeted with a mix of fear and curiosity and as I entered the village centre I was asked to visit the school to talk to the children. They crowded round as I told them of my journey. I asked them what they knew of local wildlife and they seemed to know the animals that could be found locally including baboons, hyena and kudu.

A village headman related the story of Arap Leso. He

Jennifer

Jennifer

Jennifer is a trained teacher from Kamar but has to make chapattis and tea for a livinglived a few kilometres outside of the village and, like others, had herds of cows and goats. But he also took pleasure in the wildlife that lived in and around his home, particularly the Greater Kudu, that shared water and browsing resources with his livestock. Like other pastoralist societies such as the Maasai, the Tugens, have a traditional respect for wildlife. Their livestock and wild herbivores feed alongside one another. Thoughtless killing of wild animals, in traditional culture, was, if not taboo, disapproved of. Even today antelopes such as gazelles often follow livestock back to their shambas in the evening. Old wzee still maintain these principles. Particularly within the sphere of influence of Bogoria young people also have an understanding of wildlife conservation but from education and knowledge imparted in schools. However I was to find that the middle age groups of men in particular where much more inclined to hunt (poach) wildlife. Maybe this is due to lack of knowledge gained either culturally or in school or because of the direct needs of the family.

River Molo The colonial road continued and followed a high route above a deep gully. Cows grazed on impossibly steep slopes on

River Molo

River Molo

Matayo by the River Molo at Sirimtathe other side trying to search out any meagre blades of grass that they could find to sustain them. Finally we made a steep descent to Sirimta and the crossing of the River Molo which in this dry season was less than knee high. In the rains it would be impossible to cross and I received several requests to try to find funding for a bridge so that people in Molos and Kamar could get to the weekly market in Radat.

Our campsite was on the river bank under the ubiquitous riverside fig tree. The sides of the deep ravine rose above us as we erected tents. It was here that I received my two Kalenjin names. As evening fell we received a delegation of chiefs and headmen from the local village. They were eager to welcome us and felt that my presence could be a new era for ecotourism. I had to diplomatically both acknowledge that tourism may arrive but also dampen down expectations of sudden riches from the hoards of wzungu who would follow in my wake. In reality I believe that trekking will bring a few more travellers but I doubted if it would be in

Hornbill

Hornbill

Hornbills are common in the arealarge enough numbers to make significant difference to life. However where people have next to nothing even a few visitors will make a difference if they contribute to the local economy by hiring local guides and buying a few food supplies from the villages through which they pass.

At this beautiful camp in Sirimta, numerous birds fluttered about the riperian woodland and high above an eagle soared. I was told of the caves further along the river that had been used as refuges in cattle rustling wars between the Tugens and the Pokot. I was taken to visit the Kabarak swamp, which I was told was a wonderful place for birdlife but after a long and dusty walk all that was there in this high drought was a muddy hollow and a few cows grazing in the browned remains of the reed beds. A solitary dark chanting goshawk studied the marsh from a lone acacia and a hamerkop strolled around the edge of the mud looking for frogs.

I met several women along the route grazing their goats and was offered warm milk, fresh from a cow. However even though it was only 11 in the morning at

Pit

Pit

Pit near the river Molo where boys celebrate their initiationone banda the residents were already inebriated from their busa (millet beer).

Molok We walked back to camp via the small village of Molok and I stopped at a local clinic to talk to the two male nurses. Raymond eloquently told me about the hardships of running a small medical centre in such a remote location. Patients would walk 15 kilometres or more to get treatment. Women with babies lined the benches outside the building and kept arriving as we talked, often dusty and tired from their trek. I compared their trek of necessity with my trek as research. Many of the people did not believe that a mzungu could walk so far and why would they want to? Where was my vehicle? One of Raymond’s concerns was the lack of a fridge in which to keep vaccines and serum. This meant that anti-natal clinics had to be help on the day on which he received the vaccines. Snakebites are also relatively common in the area, yet victims have to travel another 20 kilometres to get treatment. One day Raymond also dreamed of getting funding to build a maternity wing but at the moment they coped with two

Molok

Molok

Raymond, the nurse at Molok, with mothers and babiessmall rooms and scant medical supplies. Over $1billion is given annually to Kenya in aid from the ‘developed’ nations. As many have asked before where does this go? William Easterly (2006) in his book The White Man’s Burden asks why large ‘Aid Schemes’ are so ineffectual. His answer is that the scale and approach is wrong. Aid is not effective when designed by Planners from afar. It needs Searchers with knowledge at local levels to help local people design ways in which aid will work in their own situation. Has anyone in USAID thought about giving Raymond a fridge?

In the village centre, although I was hot, thirsty and feeling exhausted from the midday heat I talked first to the school children in the small school and then to some of the older wzee and mamas. The children knew vaguely of some of the mammals found locally such as baboons who raided the crops. The older people remembered times of plenty, grassy plains and wildlife that co-existed with their livestock. Now they believed that it was drier and they suffered from poverty.

My local guide later walked with me along the river to see where one enterprising farmer

Molok children

Molok children

Talking to school children in Molokhad managed to install a water pump to irrigate some of the low lying land along the bank. From his small shamba he produced green vegetables which he sold to other residents. In a different direction I was shown the remains of a ceremonial pit used by boys to shower after their period in isolation after circumcision. These rituals now though were curtailed and confined to school holidays, education taking precedence over traditional practices.

Radat The following day we walked the few kilometres to the main road at Radat through arid land and acacia scrub. Although the sections of trail in this section of my walk from Maji Moto to Radat had been short the heat made it tiring and it had also given me the opportunity to get to know more about the lives and culture of those I met along the way. Travelling with donkeys rather than a vehicle had also given me another link back to the time of Arap Leso and the colonial travellers.

As I entered Radat I passed a large storage area for sacks of charcoal that were sold on the roadside. Charcoal is one of the two main products of

Erosion

Erosion

Gully erosion near Molokthe area, both based around the acacia trees, the other being beekeeping for honey. In this area of poverty these two products were essential although one is beneficial to the environment and the other seen as detrimental. However charcoal burning remains a key part of the local economy.

Honey is another traditional product. The hollowed out trunk of trees turned into beehives are a common sight throughout the central Rift Valley. At Radat, and other villages on the main road from Nakuru to Kabarnet, honey kiosks lined the roadside surreptitiously placed by the road bumps where cars had to slow. Women waited there patiently to wave old whisky bottles full of golden nectar at the passing drivers in the hope of making 100KES (less than £1) per bottle. One sale would feed her family for that day. Conservationists working in these arid areas try to encourage honey production in preference to charcoal burning as a sustainable economic activity. As the hives are hung in the acacia trees and the bees collect pollen from the acacia blossoms honey indirectly encourages preservation of the acacia woodland.

Radat to Tinamoi At Radat I felt that the second half of my journey

Charcoal

Charcoal

Charcoal burning is common but felling of trees can cause erosionbegan. The road was an invisible divider that restricted association with Lake Bogoria National Reserve and its sphere of influence. It was the administrative boundary between Bogoria and Koibatek Districts. Here also my guide changed and I was met by David Rotich Sirikwa. He was commonly called Rotich although his circumcision name Sirikwa was the one he was most proud of. David was his Christian name but I felt that it was a tolerated bestowal of identity and rarely used. Matayo also asked to voluntarily accompany me to learn more about The Trail ahead, again showing an enthusiasm to learn that I found inherent in most of the Tugen people that I met.

Our first obstacle after leaving Radat was to cross the Perkarra River. My guides were concerned that I would be able to cope with the knee deep crossing. The alternative was a detour of 15 kilometres to the bridge further along the road. As we walked down to study the crossing the councillor told me of the value of the river Perkarra. As everywhere across these arid lands water is a primary concern This river is used for everything: irrigation, drinking, washing and food. “We can

Beehive

Beehive

Bee-keeping is a traditional livelihoodget fish as big as .. as big as I am.” the large man proudly told me. I never failed to be amazed and slightly sickened at the sight of people drinking brown silted water wherever I went. I was always conscious of water and its purity and religiously refused to drink anything but my own bottled water or occasionally treated water. My companions often joked to me about the strength of their stomachs compared to mine and how this water was fine for them to drink.

Despite their concerns the crossing was easy and we were soon clambering up the steep cliffs on the other side from which I could look back at the escarpments where I had started, now fading into the haze on the horizon. Walking a trail gives me the excitement of walking towards new horizons but also fleeting glances back and opportunities to reflect on where I had come from.

Rotich told me about the recent changes in the vegetation of this area. Only ten years ago this land had been covered in grass and despite small pockets of degradation and erosion was good pastoral land. However the invasive hopbush shrub was introduced

Honey

Honey

Bee-keeping is traditional and honey is sold in old whisky bottlesand quickly took over. Now the land is thickly covered by Tipilikwe (Dodonaea angustifolia/viscose). Now we had to walk through green tunnels 2 metre high. However Rotich was still able to show me the tracks and distribution route of Greater Kudu and although I did not have time to visit it the local communities are setting up a sanctuary in the area.

Tinamoi At mid afternoon we arrived in Tinamoi, our destination for the day and set up camp on the edge of the primary school under a conical hill called Kabuot. We were an instant attraction as hundreds of purple and blue uniformed children circled round curiously watching as our tents were pitched. After talking to them for a while I set off for another journey that day to see Rotich’s koko (grandmother) who was a medicine woman. As we strode along through the shrubs the rain clouds gathered behind us and the 6 kilometre walk seemed endless. At last we arrived at the closely packed hedge of her banda and crawled in through the narrow gateway to a barking of dogs. The 80 year old koko was delightful, welcoming and excited by our visit. After a

Perkarra

Perkarra

The councillor at Perkarra Riverfew introductions I asked if she would tell my camera about her life and the medicines she used. She agreed but, as all women would, asked if she could change out of her dirty work clothes. She re-emerged from her hut in a pretty floral dress donated to her she said by some wzungu missionaries. She had been saved by Christianity she said about 5 years previously and asked me if I had received God.

She then talked knowledgeable about the natural remedies that she used and the way she had grown to know of medicines through treating local women and children. She was proud of her knowledge and commented that she would love to train one of the younger generation in her craft. When I asked if she would show me some of her herbs she produced an old fertiliser bag full of, to me, unidentifiable pieces of wood. She sifted through them looking at the colour and texture and tasting or smelling them and confidently told me what they were and what they were used for. Her biggest regret was the scarcity of one particular plant, Mormorwe, that possessed many strong medical powers. It had, she said,

Koko

Koko

The koko (grandmother) of my guide, Rotich, is a medicine womanonce been common throughout the area but now she no longer knew where to find it. A mzungu had come and harvested all the tress and taken it abroad. She was angry that this plant had been stolen and was no longer available for local people to use. This I was to discover was sandalwood. Now it’s felling and export is banned by the Kenyan government, and later on my trail when I was shown a tree and picked up a small twig, I was told to hide it in case an askari (policeman) stopped us. Sadly I had to leave the koko and she too regretted that I had not time to spend a day with her. I asked if I could help her in anyway and she asked if I could help her get medicine to bring back her failing eyesight. In this I was able to help as I had a pair of off-the-shelf reading glasses in my bag. I left her delightedly wearing them perched at an angle on her face.

As we raced back to the camp before night fell and rains overtook us, Rotich showed me the overgrown runway that missionaries had built

children

children

Children met on the trailsome years before. We also scanned the bushes for bush babies but apart from a scrub hare saw little wildlife.

In the morning I received a visit from some of the local chiefs, including a woman chief. Benson Rotich was the chief of Bekibon location and Maria Kiptoi and David Yator were assistant chiefs. I asked Maria about the challenges and opportunities of becoming a woman chief in this traditionally patriarchal society. She said that slowly attitudes were changing and that she was thoroughly accepted by the community. Most importantly for her was the fact that she could act as a role model for other women and young girls. She was particularly concerned for girls to receive a good education but was unhappy that many still dropped out of school due to pregnancy. Raising awareness of the equal opportunities for women was vital.

Tinamoi to Tenges As we progressed away from the influence of the conservation ethics surrounding the lake and the National Reserve management and education facilities peoples’ awareness of conservation issues and the sanctity of wildlife slowly seemed to diminish. I talked to some of the children from the primary school at Tinamoi and they

donkeys

donkeys

Donkeys carrying luggage on the Tugen Trailsaid they had studied little about conservation and they seemed unaware and disinterested in ‘wildlife’.

From Tinamoi, we slowly started to gain altitude and consequently the vegetation, geology, soils and climate also changed. We crossed a series of seasonal streams and the vegataion became more lush. Ahead of us the Tugen Hills rose, the steep slopes and conical peaks of some of the hills proclaimed their volcanic origins. Rotich, having inherited some of his grandmothers skilled with plants showed me some of the trees and shrubs that they used and described their uses. Uswe is used as a milk preservative, arwe is a riverine tree that has edible seeds, komolwe and muyengwe both have edible fruits and one of the euphorbia species is perfect for making arrow carriers.

We started to climb more and more steeply and I was taken up scrambled shortcuts while the donkeys plodded on along the winding road. Although I had already cleaned my teeth that morning I was presented from a twig of the Sokotoiwo or toothbrush tree. I mimicked the others and stripped off the bitter tasting bark to use the hard centre to scrub at my teeth and gums. I was

Tugen Hills

Tugen Hills

The Tugen Hills in the distancetold that this natural toothbrush contains whitening and cleaning properties and is certainly hygienic as it is used once then thrown away. Matayo suddenly dived off into the woodland saying - here it is, pulled off a splinter of tree from a chipped area on the truck and handed it to me to smell. I recognised instantly the incense smell of sandalwood. A few trees still remain, normally deep in the forests, and are heavily protected by law but I wished that I could have bought Rotich’s koko here to replenish her stock of medicine.

Climbing the wooded slopes to Tenges we started to meet men, women and children descending the steep path carrying bags of grain or handfuls of vegetables. Today was market day in Tenges and people from miles around had climbed or descended to the weekly sale of food and livestock. Most were surprised and curious to meet this mzungu woman walking on their paths. Where was my car? Why was I there? They did not know that wzungu could walk. In Kenya it is polite custom to shake hands with everyone, young, old, male, female and I soon got used to the feel of sweaty,

Anderson

Anderson

My assistant, Anderson, and one of the many friends he made on the walksticky or dusty hands in mine. Many of the men and women were overly happy and as they passed the smell of busa filled my nose. One man, smiling happily,shook my hand and greeted me “Chamgei.”, then, not letting go, continued, “Gebe olinyo” with a glint in his eye. Quick thinking I said “Gebe Tenges” and headed off up hill. The others laughed at my understanding of Kalenjin although all I had known was gebe, “Let’s go!” ; but had half guessed the meaning of ‘gebe olinyo’ which means “lets go to my place!”.

Tenges We reached Tenges through a damp, resin scented pine wood. The Tugen people live across the Mid Rift Valley in a region that consists of two distinct climates and environments: the semi-arid lowlands and the lush forested highlands. The arid lands of the Baringo area were suddenly left behind and here in the hills were old and new forests. There were many plantations of exotic species such as these conifers as well as fruit trees such as papaya and mango. In fact we were to spend the night in a disused tree nursery near the District Officers office.

The tree nursery was

vegetables

vegetables

Local vegetables for sale at Tenges marketsituated rather forlornly behind locked iron gates. But inside was a pretty steeply terraced lawn leading down to a fast flowing stream. There were still specimen trees growing there, mostly exotic species. The tree nursery had failed in that location as the stream was seasonal so they had moved to the banks of a different river where they could get water for irrigation all year round. The trees being planted are mostly fast growing non-native species such as Cyprus and eucalyptus although a few endemic tree species are grown. Regeneration of forests is seen as important in these hills to stabilize the soil on the steep slopes, to bring rain and for timber and commercial crops.

I was told by the DO that there were plans to site a secondary school on this site but that could take years to achieve. For the moment we were to use it as our campsite. I left some of my friends setting up the tents and headed off to catch the last of the market.

The market was closing down, There were stalls selling cloths, hardware and food. Food in the arid lowlands in limited: goat meat, ugali (maize starch), rice,

Camphor

Camphor

Giant camphor tree on the Tugen Hills. sukumo wiki, tomatoes and onions were the staple fare and all that one could buy in most lowland villages. Here there was a colourful array of fruit and vegetables. Mangos, avocado and herblike vegetables called kisochon and kisakiande. Many of the old people say that these natural wild vegetables are more nutritious than the cultivated sukumo, the local greens that are now grown as a staple food.

When I returned to camp I found that all the tents had been moved under the shelter of the disused Potting Shed. The DO had come to the camp to warn us of heavy rain that was forecast overnight. As it grew dark the air felt cold after the heat we were used to in the lowlands. Rains had finally come to the Rift Valley three months later than normal and just as I was embarking on the higher sections of my trek. As we ate our evening meal, including the delicious local greens, I heard a hissing rumble approaching our shelter and within minutes the rain was lashing down. I understood why these hills had so much more lush vegetation that the lowlands.

The Tugen Hills In the morning we

Mt Kenya

Mt Kenya

Mount Kenya can be seen just before dawn from the Queen's Camp at Sachocontinued climbing up hill until we gained the ridge of the Tugen Hills. I was amazed as we came out onto our first vantage point west across the Kerio Valley to the high cloud covered escarpments beyond that were our final destination. The Tugen Hills are an uplift in the centre of the rift Valley. The views to either side are stunning and I felt like an eagle poised above the world. I was amazed that the environment could change so rapidly. We were 1500 metres above the valleys below.

Our walk continued along a tarmac road. Rich looking houses and farms amidst forested hill tops lined our route. This area was the birthplace of a previous president of Kenya, Daniel arap Moi and his influence in creating a more wealthy area I thought was evident, yet local people disagree. Certainly the area felt more prosperous. Glimpses of the slopes of these hills showed a patchwork of terraced fields and woodlands. The cattle were healthy and plump and the numbers of goats foraging along the roadside was distinctly less than the valley floor.

At Tenges we had been joined by my guide for the Tugen Hills, Nicholas Biwott.

Tugen Hills View

Tugen Hills View

View from the Tugen HillsNicholas told me about the Forest Reserves that capped most of the hil tops along the ridge of the Tugen Hills. Theses areas were protected for the use of the local communities. They were now a mix of native and non-native tree species. Although extraction of wood was regulated by law there was evidence along the road side of felling of some of the more valuable species, particularly the rich smelling red cedar. Where a tee had been felled the brilliant red shavings glistened in the sun, made more brilliant from a passing rain shower.

I paused to talk to an old lady who laughed and chatted with Anderson. She asked for a few shillings for tobacco snuff but obviously wondered why I was there at all.

We stopped at a roadside café that I was told that this was a regular stopping place for Moi in the past. I was delighted that they could make me lemon tea - such a relief from the milky sweet African chai. The mandazi (doughnuts) were sweet, light and heavenly.

As we approached Kiptagich and the DOs office for Sacho I stopped to talk to a group of women enjoying

carrying wood

carrying wood

Woman carrying firewoodthe sunshine. They quickly invited me to sit and join them which I gladly did. They all seemed happy with their life here overlooking the lands below. I was given my favourite meal of githeri as a sign of welcome.

The Tugen Hills are refreshing after the heat of the valley although our campsite was somewhat soggy. I was welcomed by the District Officer and chief. Nicholas took me off to explore some of the local hills. After a short steep climb through a farm pasture and then up a wooded hillside we came out to look at the view. This hill is called Kokop’soo Hill, literally grandmother initiation but in other words it is a hill used for the ceremony of female circumcision. I was told that the hill was no longer used for this ceremony but as I got to know women in my study area better I realised that despite being illegal now in Kenya the practice is still maintained. This hill top still had signs of being used and an aura of being a sacred site. I was not certain but when I wandered off along another, higher path I felt my guides were slightly

uneasy. Again various medicinal plants were identified including Chomiswe, used as a balm for inhaling. I also found a patch of small pink orchids.

I had already been to the Tugen Hills a few weeks earlier with a small expedition organised by William Kimosop. The others in the party consisted of a friendly and knowledgeable group of photographers and conservationists and, despite having malaria at the time, I managed to explore and walk with them. We camped on an eagles perch at the ‘Royal Camp’. The early morning, pre-dawn, sight of Mount Kenya 100 kilometres away is something I shall always remember. It was there on the horizon for only a brief few minutes just before the sun rose and the haze obscured the view. The name of the campsite was coined by William after researching the royal safari by the then Princess Elizabeth to Kenya in 1953. A couple of days before she planned to stay in the Tugen Hills, Elizabeth received notification of her father’s death at Tree Tops in the Aberdares Range and had to curtail her visit. So this was a royal camp that never was.

William paid us a fleeting visit in Sacho

Umbrella

Umbrella

Nicholas and Matayo share my umbrella when it rains in the Tugen Hillsto see how I was progressing on the TransRift Trail. He was accompanied by a mzungu who owned a tour company and was looking at the possibility of developing the Royal Camp for an exclusive tented camp. Tourism is slowly starting to enter these special hills, I hope that it comes with a sensitivity to the environment and the Tugen people who live here. They need the income but at what price? The emphasis of the walking trails is to make sure that the local communities benefit from use of locally run community campsites and purchase of goods and services along the route. The problem for communities is the lack of knowledge of marketing and understanding of customer care. Although successful in other areas of Kenya ecotiyrism requires sensitive introduction into these new areas.

Although my trail this time was across the Rift Valley the Tugen Hills offer stunning walks through forests and across ridges. There is ample birdlife and the opportunity to sight mammals such black and white colobus and blue (Syke’s) monkeys and the pure beauty of the area well compensates for the lack of the larger mammals that seem to be the limited focus of so

Two crossings

Two crossings

River above Kapkelelwe. Nicholas told us we would have to cross the river 'two times', then repeated that advice four more times!many tourists. These forests need protection and although they are designated Forest Reserves in many places there must be a temptation to exploit the timber resources. A magnificent giant by the roadside, a 40metre high camphor tree, kept our ‘Royal’ party busy with cameras and in any other circumstance would be a tourist attraction in its own right. The common perception of Kenya is that it is a country of big game and savannahs but step away from the regular centres of tourism and there are other places which in other circumstances would be a major attraction in themselves. The MidRift Tourism and Wildlife Association is using this fact to try to create an alternative Kenya for tourists and to advertise these “most dramatic and spectacular sights in all of Africa.” as William expressed it.

William has overseen the building of a new Equator Centre in Mogotio, the gateway to the Central and Northern Rift regions in Kenya. Here will be housed information of the tourist facilities in the Rift Valley both independent and community owned. From here the plan is to organise guides, donkeys and provide transport for trekkers on the Trans Rift Trail. Community based tourism can

Kapkelelwe

Kapkelelwe

School children at Kapkelelwesuffer from the lack of marketing knowledge but the provision of a central coordination centre and linking of a series of community initiatives in well organised ‘circuits’ has the prospect of generating an alternative form of tourism in Kenya.

After a stormy night in our less than royal campsite, I interviewed the District Offcer, the chief and District Agricultural Officer about the impact of changing agricultural practices on the environment and the changing environment on livelihoods. Although these hills appeared prosperous in comparison with the arid lands below the people here also suffered from poverty and hardships. Because of the fertility of the soil, slopes were being converted to grow cash crops, particularly maize. This meant in some circumstances people were not planting enough food crops for themselves so that at certain times of year there was food shortages. Also the clearing and terracing of land may lead to destabilisation of the soil. Further north this has led to extreme siltation of Lake Kamnerok, home to a large crocodile population and the reserve also supports hippos, elephants and other wildlife. This is a warning that the highlands and lowlands impact on each other environmentally, culturally and socially. Local issues

Kimerer

Kimerer

The fluorspar quarryare also regional issues.

The Kerio Valley After two wet, cold nights in Sacho we were all glad to pack our tents and set off into the Kerio Valley. Nicholas was our guide and we were heading to Kapklelwe 1000 metres below. He told me that on his own he could complete the 10km journey in less than an hour. I wondered how my guides felt about plodding on at my pace and all the endless stops to meet and greet people. Yet I think they also found it interesting and were discovering the value of their own cultural knowledge that they could apply in guiding people through the area.

Not far from Sacho we passed the steep farmlands of Nicholas own family. His uncle, once in the Kenyan army, stood tall and straight as he offered us oranges straight from the tree. Further down the path we met an old man walking up carrying one small pineapple and I was told that h was climbing to Sacho to sell it for 20 KES (15 pence). The old man was in his 80s but a few years previously he had tasted pineapple for the first time.

Chamloch Gorge

Chamloch Gorge

A more scenic route across the Kerio Valley is via the Chamloch GorgeHe liked the sweet flavour and decided to grow them himself as a crop. Diversification is not just for the youth and even the older people look for ways to diversify their income in this modern world.

The crops on these westerly slopes seemed more varied than the Baringo valley. Beans, fruit trees and vegetables as well as maize are grown. The farms seemed prosperous. I joined one family in their banda where I could try the local honey beer. This was once drunk only by village chiefs and wzee but younger men and women now used it as well as buza. The taste had a raw bitterness that melted into the sweetness of honey.

As we continued down Nicholas decided that we would risk a short cut even tough it meant crossing a ‘couple’ of rivers. As we descended into the woodland he said that kudu could be found here as well as other antelope but that they were often poached, particularly in times of famine. He himself, as I suspect many of my other guides, had once been a poacher and many of the people that I worked with would whisper ‘sweet meat’, at the sight

English Breakfast

English Breakfast

At Sego. This is the first time my team had eaten an English Breakfast of a gazelle or dik dik.

At last we scrambled down to the fast flowing river and removing boots and socks waded across although I found it hard to stand against the strong current. The next crossing was slightly easier although the fourth and fifth were tricky. I started to wonder how many crossings we had to make. ‘Two more’ said Nicholas. At the third crossing it was again ‘Two more’ and so on until it became a joke between us. Finally after over ten fords we crossed the river one more time and then climbed a small rise into Kapkelelwe.

At Kapkelelwe our camp was in the compound of a school just above the river. The children here kept a wary but curious distance but were pleased when I went over to speak with them. At the African Inland Church run secondary school, I talked firstly to the deputy head teacher. He told me that there was little wildlife remaining in this region and that poaching was rife. When I asked about Tugen culture, he commented that the Tugen people really had an in between culture or no culture. They were neither traditional in beliefs nor Christian.

From my guides I learnt that Christianity had subsumed the local god Asis. Asis is also the name for the sun and the god lived in the east where the sun rose. The church has become central to many people in Kenya with a wide variety of denominations. Most however now use a hybrid approach to the teachings of Christ and incorporate or adapt local traditions of song and dance into their worship. Many Tugens I found followed both Christianity and traditional practices that seemed to coexist in harmony. The older children at the secondary school were glad to talk to me and although I wanted to discuss their lives they were keen to exchange information with me and try to understand about life in England.

In the village itself a group of men were making arrows and were suspicious when I approached to talk to them. They seemed to think I was an informer for the police or government. Bows and arrows are common here and always I was told that they were purely to defend their livestock against wild animals.

Our planned journey the following day was a long 30 kilometres stretch. Because of the rains

beans

beans

Drying beans on the slopes of the Elgeyo escarpmentand uncertainty about crossing the side streams of the Kerio River we opted for the safer but longer journey via the road and the fluorspar mines. We had left the cool damp highlands behind for the time being although ahead the escarpment was shrouded in cloud. Here we were back to the semi-arid lands of acacia scrub. Along the roadside the land was divided into farms by sisal and aloe hedges. Some of the shambas were cultivated and grew beans or were planted with fruit trees. However many were unused. There were also large regions of deeply eroded gullies. At last we came to a shallow ford across a tributary of the Kerio river which marked the boundary between the Tugen lands and the Keiyo. A century ago this had been the site of inter-tribal wars and the Keiyo had wiped out a whole ageset, the Maina, from Tugen history. In fact Rotich had told me about his great grandfather who had been one of the few men to have escaped from the Kerio valley to set up a new home near Bekibon.

So here my Tugen Trail really ended but I was to complete my full transect of

Choroget Wzee

Choroget Wzee

The wzee at Choroget at the end of the trailthe Rift Valley by walking as far as Choroget at the top of the western escarpment. In many ways meeting another similar tribal group enhanced my understanding of the similarities and differences between the Tugen culture and others.

The Kerio Valley seemed much more intensively farmed and developed than the Baringo Valley. My road led me towards the fluorspar mines at Kimerer. It was hot, dusty and the road headed in a perfect straight route towards the white blur on the far edge of the valley floor that was the reservoir for the mine area. I came across a quarry on the side of the road where a noisy JCB was excavating gravel for road building. After the cool tranquillity of the rest of my travels this brought a stark reminder of industry and ‘civilisation’. As we neared the mining area a large noticeboard warned of the hazards in the area. “You are now entering mine tailing dam area. CAUTION! SAFETY GUIDE. To avoid injuries or fatalities please keep away from the dams. Herding of livestock is not permitted in this area. Herd at your own risk.” A few hundred yards further on cattle were grazing.

Another sign of

Guides

Guides

With all the guides at the end of the trekenvironmental pollution and efforts to keep people and livestock out of harm was rings of barbed wire around a green looking pond and swamp. A large mud embankment looked from the road like the edge of a pandam but when we climbed to see it was the dumping ground for the mine waste and we beat a swift retreat.

At last we reached the bridge over the Kerio river although at this point it was narrow and disappointing. I regretted not risking the alternative route across the Kerio valley which was downstream and away from this industrial scar on the environment. Later I would visit that bridge and admire the fast flowing river rushing through a deep gorge. I reflected that it would be a much more pleasant route for tourists on the TransRift Trail.

However this route via the fluorspar mines gave me the opportunity to see another aspect of life in the Rift Valley and the dangers of resource exploitation. I stopped to talk to two local men on the bridge. They complained that the company Kenya Fluorspar (EPZ) Ltd rarely employed local people except as occasional cheap labour. The damming of the river and use

Nyama Choma

Nyama Choma

Eating nyama choma with the wzeeof the water in the processing plant had polluted the river and made it undrinkable for humans, and in some instances, livestock. There has been no compensation either from the company or the government.

For the next few kilometres I shared my trail with noisy polluting trucks carrying heavy loads from the mines to the plant. An old woman carrying a heavy burden of firewood complained about the distance she now had to travel to get it. Another family on the edge of Kimerer gave my companions drinking water. As the children shyly came to shake hands with the mzungu their mother said that her life was improved as her husband worked for the company. She was prepared to put up with the rumbling trucks and polluting dust for the improved income for the family. As we rested in the village, I saw a different aspect of life here. Jerop, my gentle female cook, complained bitterly about all the rude comments we were receiving from the men lazing drunkenly about the town. After the normal polite and interested communication I had had with Tugens across the rift, this town of mixed tribal workforce was an indication of what multi-tribalism

Kudu

Kudu

Male Greater Kuducould bring. We moved on quickly after lunch to find cooler more pleasant trails.

A few months later I followed a different trail across the Kerio Valley via the Chamloch Gorge to try and find a more peaceful route for the tourist trail rather than following the noisy road via the Fluorspar mines. The new route was indeed better apart from the whistling calls of hunters hunting for a cat, probably a caracal or serval that was threatening their scrawny goats. Shortly after, we had a sight of a large group of bare torso men carrying one small dik dik. This morsel would serve as a meal for around ten families. When poverty is so extreme I had mixed feelings about poaching/hunting. When I told William what I had seen, he replied “THAT is why we are developing the TransRift Trail”. The end of that day we arrived at the dramatic gorge on the Kerio River where Dennis has entrepreneurial plans to build a campsite for the benefit of his own village.

Another half an hour and we finally came to the quarry itself and the end of the stream of trucks. I wondered how this quarry had

Rainbow over Bogoria

Rainbow over Bogoria

Rainbows often follow rain storms at Bogoriabeen planned and developed and who was prospering from its construction.

Sego, the Elgeyo Escarpment and Chororget The last six kilometres of my thirty kilometres walked that day were refreshing. Although my legs were tired we were entering a pleasant green area again. Above us the final escarpment loomed, its head in the grey clouds above, and I wondered if I would manage the steep climb the next day. William had warned me that the climb up to Chororget was difficult and as yet we were unsure of our way. At last we arrived at the Sego Safari Club Hotel. William and my driver Dennis, had arranged with the manager for us to camp in the grounds. At the end of my 140km trek from Mochongoi the small luxuries of a swimming pool, even unheated and chilly, warm showers, European toilets and a bar were welcoming. Dennis, as usual, had efficiently set up camp and cooking for the evening. So we prepared our bodies and minds for tomorrows climb opting for the easier but slightly longer route. In the morning I treated my Tugen companions to a ‘Full English Breakfast’ in the hotel restaurant. For 200KES (£1.50), we

Equator

Equator

The new Equator centre for tourists near Mogotiohad juice, fruit, sausage, bacon, egg, toast and tea.

Our guide for the day was a weather-beaten, tall long-limbed Keyio. He described the climb as being in three zones, lower, middle and upper slopes, each with its own vegetation and land use. He led us off in the cool early morning through fields of maize and beans on the lower slopes. We soon attracted a following of other people making the climb to visit their shambas on the higher slopes. Two young girls with bare feet bounded goat-like up the stony path in front of me. They had their main home on the lower slopes but pastures and shamba on some of the more fertile slopes higher up the escarpment. Part way up our initial climb I heard echoing calls from the valley floor below. It was Sunday, and I was told that it was a party of local youths getting together to hunt wild pig that were destroying their crops. I wondered what other wildlife they would also hunt that day.

Half way up our climb the land flattened out and we came across an area of intense productive agriculture. The shambas here were well watered and prosperous growing a diverse range of crops from beans and maize to coffee and fruit. There were few cattle but they were fat and healthy. I spoke to a young mother at one shamba, despite the frightened wailings of her young baby at the sight of my strange white visage. She said she was happy with her life here. They had good crops and a pleasant environment in which to live. As I gazed out across the aridness of the rift valley below I wished that I could set up a home here too amidst these warm and friendly people and with such a panorama. At heart the Keiyo are similar to the Tugen coming from identical Kalenjin roots.

Our climb continued and buttresses of bare rock towered above us. Although steep the path was not too hard although in places the wet mud made it slippery. Soon the farmland was replaced on the steep slopes by remnants of primary forest and bamboo thickets. One bamboo root was dug up for its medicinal value.

Normally my Tugen friends could go all day without drinking even in severe heat, but this energetic scramble was hard on my lowland-living assistants. Despite constant urgings, they always forgot to carry water so as we gasped and panted up these slopes I got the request “Assist me water.” Foolishly I did, depleting my own supply. Later when we came on a clear looking spring I filled my bottle, against my normal strict rule of drinking only bottled or purified water, and suffered the consequences a couple of days later.

Suddenly, as we climbed, someone whispered loudly, ‘Colobus’. On the opposite slope of our winding path a group of four black and white colobus were feeding. I was delighted. These monkeys are increasingly rare, inhabiting the remnants of the Sub-Saharan forests. Their distinctive black and white fur have made them status symbols for tribal ceremonies although taboos on reckless killing have also helped preserve them. Simultaneously, someone called ‘What’s that?’ and I turned to see another two dark, monkey-like creatures bound across an open area of rock. There was no flash of white so we didn’t think they were more colobus but possibly blue monkeys, which I had seen previously in the Tugen Hills. This small forested chasm climbing up to the plateau above was a haven for wildlife, yet had no statutory protection, nor, from what I could find out, had it been thought of as special. Again it was another pocket of nature that has gone unnoticed.

Finally we plodded up the final rise and came out onto a completely different landscape. I could have been in England. In front of me green fields of grazing cows spread out to the rolling hills on the horizon. This was a rich area that had at an early date been influenced by colonial settlers and European farming practices. I felt I had almost walked back to England. There were more recent memories of other whites. Apparently this escarpment had been the jumping off point for a hang gliding enthusiast hang glider about 20 years ago.

As we entered Chororget, two old wzee, approached in their Sunday suits, on the way back from church. They welcomed me and I explained to them about my walk. They were delighted and asked if I would return to meet their chief more formally. One of the men was of the Maina ageset of the Keiyo (that the Keiyo wiped out in the Tugen society) and he was probably about 90 years old yet still strong and upright and an advertisement of the healthy lifestyle here. He remembered going to serve in the second world war with the British. However, just as they had agreed to talk to me on film, a group of younger men who had been drinking came up and started to demand money. I found it a sad reflection on the changing values of respect and hospitality that all the tribes in the region show. My older friends took me aside and I agreed one day to return to meet them properly. So my walk ended on a sad note from one of the changes that time has bought these people of the Mid Rift Valley. Yet I still had an optimistic outlook for the future.

William Kimosop is currently looking for funding to develop the Trans Rift Trail and other adventure travel options in the Mid Rift Valley. It would be good to see this opening up as a new ecotourism destination which will be of benefit to the communities and wildlife in the area. I hope my walk will make a difference and writing this story may help. If you would like to walk this trail and employ the guides and donkeys en route, or to plan a trip to the area in general then email William on

greatrift.outdoors@gmail.com.

Advertisement

Tot: 0.513s; Tpl: 0.046s; cc: 21; qc: 126; dbt: 0.1322s; 1; m:domysql w:travelblog (10.17.0.13); sld: 1;

; mem: 1.7mb